The stone 'plaquettes' were unearthed by a team of Australian and Indonesian archaeologists working in the Leang Bulu Bettue cave, one of the dozens of caves scattered across the limestone-rich southern part of Sulawesi in central Indonesia.

They published their discovery in the journal Nature: Human Behaviour.

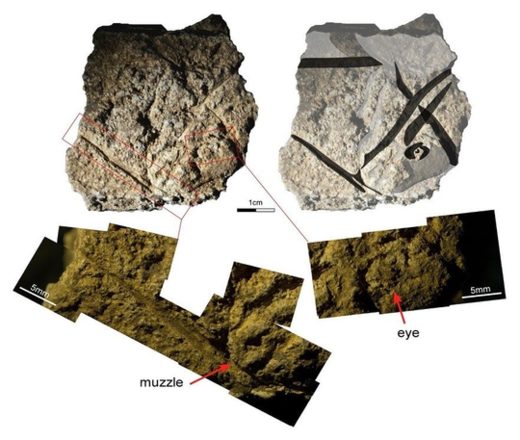

One is etched with the outline of the head and upper body of an anoa - a species of dwarf buffalo that lives exclusively on Sulawesi to this day. In pre-historic times, hunter-gatherers relied on anoa for food, and used its bones and horns for toolmaking.

The other is adorned with an eye-like 'sunburst' - an image reminiscent of a child's simple depiction of a circular sun with rays extending outwards or an eye surrounded by thick lashes.

Archaeologists led by Adam Brumm at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia, unearthed the rare finds in 2017 and 2018 from sediments rich in the refuse of daily life during the end of the Pleistocene - the last ice age that ended some 12,000 years ago.

Other artefacts, such as stone tools, the butchered and burnt remains of animal bones, as well as beads and ochre - evidence of body ornamentation - indicate that hunter-gatherers used the site frequently.

The plaquettes themselves date to a time between 26,000 and 14,000 years ago.

Both artworks are considered figurative, which is to say that they depict something real, rather than imagined.

Figurative art sets our own species apart from all others, according to archaeologist Michelle Langley who analysed the plaquettes. "We haven't found figurative art with Neanderthals or any other type of human," she says.

For decades, cave art discoveries in Europe led to the assumption that artistic expression arose in Western Europe.

"With more discoveries going on over this side of the world, we're finding that's definitely not the case," says Langley. "People were doing it over here at the same time or early. We just hadn't been looking."

In recent years, the islands of southeast Asia have revealed themselves to be a hotspot of early artworks.

In 2014, Brumm's team found 40,000-year-old hand stencils and animal paintings in another Sulawesi cave. Last year they announced that similar works had been found on the island of Borneo.

Meanwhile, another nearby cave on Sulawesi yielded a spectacular hunting scene, effectively pushing back the earliest evidence of storytelling by 20,000 years, to 44,000 years ago. That's earlier than anywhere else on the planet.

These latest finds are unique because they aren't fixed to a cave wall; they are portable and able to be transported from place to place by the people who made them.

Three-dimensional figurines and plaquettes have previously been found in Europe and the Middle East, but never before in island southeast Asia. These are the first.

But whether the practice was developed by locals or was brought to the regions much earlier when ancient humans first migrated there from Africa remains a mystery.

The archaeological record of portable art is likely rather patchy, says Langley, given that works of art on organic materials like bones and shells rarely survive the passage of time.

What they were used for can also only be guessed at. "We haven't really seen any evidence that these were created or at least discarded as sacred relics," says Brumm.

"They were seemingly discarded amidst all the other refuse of day to day domestic life." But, he adds, objects once considered sacred can lose their sacredness over time.

Other possibilities are more prosaic. They could have been used as a storytelling aid, says Langley. Or perhaps one of our ancient relatives was compelled by the same artistic urges that drive us today - "doodling while you're by the fire," for instance. "We don't really know."

Whatever their use, Brumm says their discovery highlights "how complicated and sophisticated the artistic culture was in this part of the world, far away from Europe".

Reader Comments

where the glyphs were carved.

sorry if that made no sense

You're welcome. (I do like helping and I've been text researching on computers since 1982, so I hope I've gotten better.