Denisova cave lies in a river valley within the Altai Mountains, a few hundred kilometres from the Russian border with Kazakhstan, Mongolia and China. Ancient human remains in the cave are extremely rare, but artefacts are not.

"There are lots of stone artefacts at Denisova cave, as well as many implements made of bone and antler in the upper levels," says Richard Roberts at the University of Wollongong in Australia.

About 4300 specimens have been found in the cave entrance, 14,000 in the cave's main chamber, and 60,000 in the east chamber. Maxim Kozlikin at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow and his colleagues have now studied 37,000 of those east chamber tools to get a sense of technological evolution at the site.

The oldest specimens are in dirt layers more than 200,000 years old, according to a technique called optical dating. The artefacts show that the cave's inhabitants used the so-called "Levallois technique" to make tools. This relatively sophisticated technique was popular across Africa and Eurasia at the time, and involves carefully chipping at a stone to remove large flat flakes with sharp edges that could be used as tools.

The cave inhabitants had begun making finer quality stone blades and chisels by 60,000 years ago - and about 10,000 years later, they may have been using the tools to make jewellery including bone beads, a bracelet made out of polished green rock, and what has been described as an ivory tiara.

"The stone industry shows a gradual evolutionary development," says Kozlikin, but it also shows continuity. For instance, artefacts from each period his team studied were made using stone from the same river beds.

Partly because of this, Kozlikin and his colleagues argue that the tools were all produced by Denisovans. They say this is backed up by evidence of Denisovans occupying the cave throughout these periods, including DNA that was recovered from 200,000-year-old layers, and their remains that were found in cave layers about 100,000 and 60,000 years old. As such, the tools show how Denisovan technology evolved through time.

But Bence Viola at the University of Toronto in Canada advises caution. We also know from human remains and DNA in the cave's sediment that Neanderthals were present there sporadically between about 190,000 and 100,000 years ago. They could have made some of the tools, he says.

Despite their reputation as archaeological enigmas, Denisovans probably behaved a lot like Neanderthals and made similar tools, says Viola, "which is exactly why it's so hard to tell which assemblage was produced by whom".

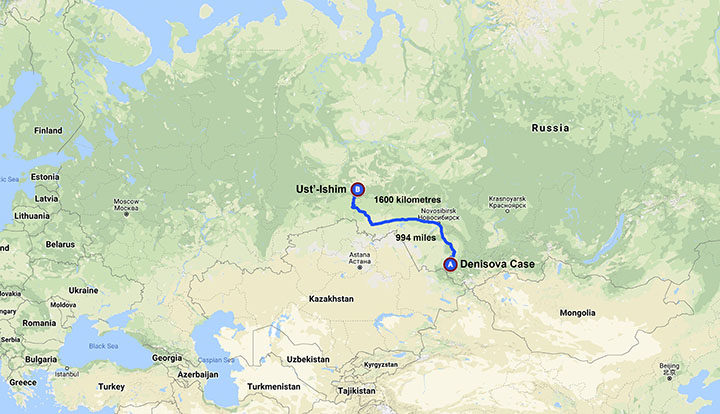

He also doubts that the Denisovans really made the jewellery 50,000 years ago, particularly since a 45,000-year-old bone from a site 1500 kilometres to the north-west shows that our species may have been present in the area.

But 1500 kilometres is a large distance: Kozlikin points out that there is no evidence - yet - that our species was any nearer to the Denisova cave so early in prehistory. As such he thinks we can't rule out the possibility that Denisovans did make the ornaments using tools they had developed over 150,000 years.

"If these researchers are correct in their findings, then there were no modern humans at Denisova during the time period when the jewellery was made, suggesting it had to be a local, pre-existing tradition that had already been developed prior to the arrival of modern humans in that region," says Genevieve von Petzinger at the University of Victoria in Canada.

"I would like to think that we have become more open-minded in the past few years to the idea that species other than our own were also capable of creating Paleolithic art - in this case in the form of jewellery," she says.

Roberts and his colleagues may be able to settle the debate. He has collected dirt samples from the cave layers containing the jewellery. He hopes to date them and see if they contain any human DNA. "We are hoping that those results will shed some light on the likely species of toolmaker of the [jewellery]," he says.

Journal reference: Quaternary International, DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2020.02.017

Comment: