It came from a supermassive black hole at the centre the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster, about 390 million light-years from Earth, and released five times more energy than the previous record holder, according to a paper to be published in The Astrophysical Journal and currently available on the pre-print server arXiv.

It was so powerful, the authors say, that it punched a cavity in the cluster plasma - the super-hot gas surrounding the black hole.

"We've seen outbursts in the centres of galaxies before but this one is really, really massive - and we don't know why it's so big," says Melanie Johnston-Hollitt, from the Curtin University, Australia, node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR).

"But it happened very slowly - like an explosion in slow motion that took place over hundreds of millions of years."

The study brought together a team from Australia, the US and New Zealand.

Lead author Simona Giacintucci, from the Naval Research Laboratory, US, says the blast was similar to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington state, which ripped the top off the mountain.

"The difference is that you could fit 15 Milky Way galaxies in a row into the crater this eruption punched into the cluster's hot gas," she says.

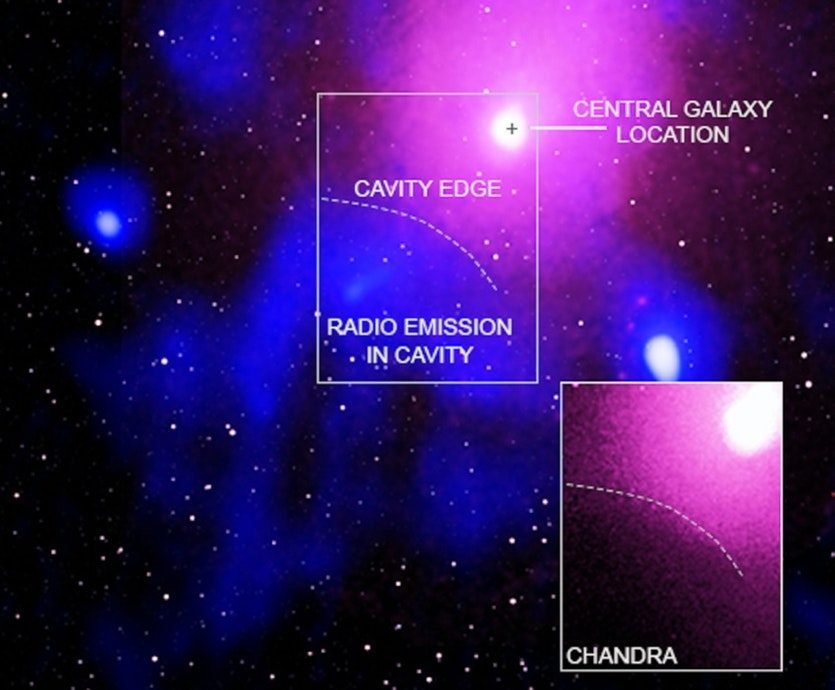

Johnston-Hollitt says the cavity in the cluster plasma had been seen previously with X-ray telescopes, but scientists initially dismissed the idea that it could have been caused by an energetic outburst, because it would have been too big.

The researchers only realised what they had discovered when they looked at the Ophiuchus galaxy cluster with radio telescopes.

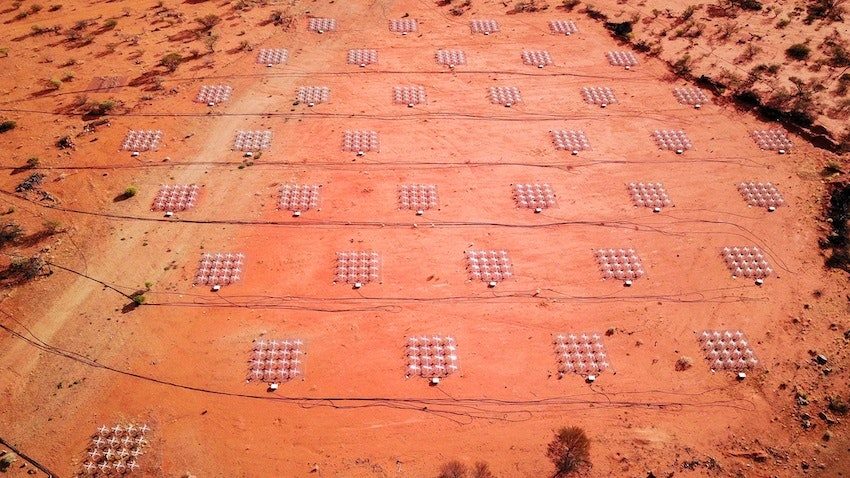

Four telescopes were involved: NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, ESA's XMM-Newton, the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) in Western Australia and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) in India.

Johnston-Hollitt, who is the director of the MWA and an expert in galaxy clusters, likened the finding to discovering the first dinosaur bones.

"It's a bit like archaeology," she says. "We've been given the tools to dig deeper with low frequency radio telescopes so we should be able to find more outbursts like this now."

And, she says, the finding underscores the importance of studying the Universe at different wavelengths.

Reader Comments

*And, even by Big Bang theory, there's 13.799 Billion Years to compare before we can claim this to be the "biggest."*

** This 'scientific' claim is directly analogous to a point I made earlier about a current events matter - Milwaukee shooting, at the below linked article. Excerpt:

Disgruntled employee shoots dead 5 co-workers, turns gun on himself, at Milwaukee Miller brewery

In one of the worst shootings in Wisconsin history, a gunman killed five people — and then himself — during a rampage Wednesday afternoon on the Milwaukee campus of Molson Coors. The shooter was...that wasn't a command....

that was a continuation. We devour our own fear and lack of knowledge, AND then regurgitate it and swallow it again.

*INdeed, though she likes killling cockroaches, she's only eaten one, barfed it back up & left that for me. For years she's known if she kills a roach, she will get canned tuna. (She was once locked in a room. I was gone. When I got back, she pushed out a dead, 2" roach under the door to the bedroom (She meowed before she pushed it out to make certain I saw it.) She got her tuna.

[Link]