It has taken researchers more than 4 years to fully wrap their minds around what happened, and their results were published just this week in the January 13, 2020 edition of Nature Physics.

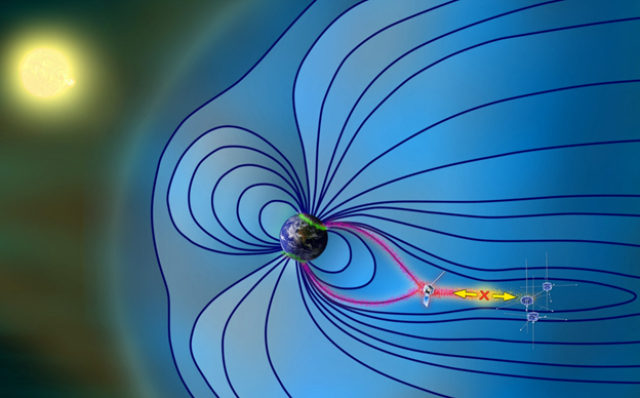

Explosions in Earth's magnetic field happen all the time, writes Dr. Tony Philips of spaceweather.com. Gusts of solar wind press against Earth's magnetosphere, squeezing lines of magnetic force together. The lines crisscross and reconnect, literally exploding and propelling high energy particles toward Earth — auroras are the afterglow of this process.

"Usually, these explosions happen at least 100,000 miles from Earth, far downstream in our planet's magnetic tail," explains the study's lead author Vassilis Angelopoulos of UCLA.

"On December 20, 2015, however, we observed a reconnection event only 30,000 miles away-more than 3 times closer than normal."

The discovery was a case of good luck and perfect timing.

Before this event, many researchers felt that reconnection at such proximity was impossible-that Earth's nearby magnetic field was too stable for such explosions ... or so the thinking went.

"Now we know better," Angelopoulos says. "The THEMIS multipoint observations are iron-clad. It really happened, and this is going to make a big impact on future studies of geomagnetic storms."

For more, see spaceweatherarchive.com.

Our universe is electromagnetic, and earth's magnetosphere is waning -fast- in line with historically low solar activity and an ongoing magnetic excursion/reversal — 'space weather' events that would have ordinarily passed by unnoticed are having an increasingly-bigger impact here on the ground.

Our modern grid-dependent civilization is entering uncertain times.

Comment: Weird 'electrical surge' detected running through ground in northern Norway - Auroras follow