But the killing of Gen Qassem Suleimani, the leader of Iran's elite military Quds force, was in a class all its own. Its uniqueness lay not so much in its method - what difference does it make to the victim if they are eviscerated by aerial drone like Suleimani, or executed following a CIA-backed coup, as was Iraq's ruler in 1963, Abdul Karim Kassem? - but in the brazenness of its execution and the apparently total disregard for either legal niceties or human consequences.

"The US simply isn't in the practice of assassinating senior state officials out in the open like this," said Charles Lister, senior fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington. "While Suleimani was a brutal figure responsible for a great deal of suffering, and his Quds force was designated by the US as a terrorist organization, there's no escaping that he was arguably the second most powerful man in Iran behind the supreme leader."

Donald Trump's gloating tweets over the killing combined with a sparse effort to justify the action in either domestic or international law has led to the US being accused of the very crimes it normally pins on its enemies. Iran's foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, denounced the assassination as an "act of international terrorism".

Vipin Narang, a political scientist at MIT, said the killing "wasn't deterrence, it was decapitation".

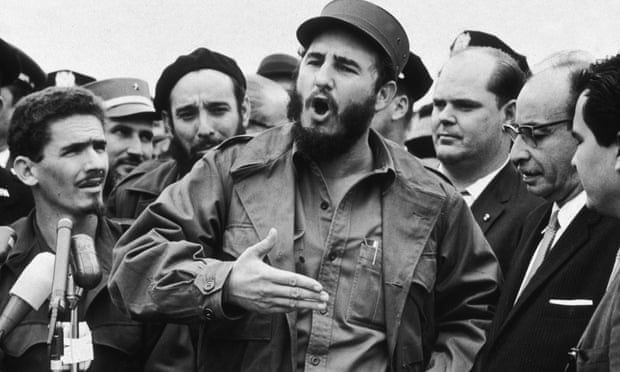

There has been no shortage of US interventions over the past half-century that have attempted - and in some cases succeeded - in removing foreign adversaries through highly dubious legal or ethical means. The country has admitted to making no fewer than eight assassination attempts on Castro, though the real figure was probably much higher.

William Blum, the author of Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, points to a litany of American sins from invasions, bombings, overthrowing of governments, assassinations to torture and death squads. "It's not a pretty picture" is his blunt conclusion.

The CIA was deemed to have run so amok in the 1960s and 70s that in 1975 the Church committee investigated a numerous attempted assassinations on foreign leaders including Lumumba, Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, Vietnam's Ngo Dinh Diem and, of course, Castro. In the fallout, Gerald Ford banned US involvement in foreign political assassinations.

The ban didn't last long. Since 1976 the US has continued to be engaged in, or accused of, efforts to eradicate foreign leaders.

Ronald Reagan launched bombing raids in 1986 targeting Libya's Muammar Gaddafi. As recently as two years ago North Korea alleged that the CIA tried to assassinate its leader, Kim Jong-un.

But most of the interventions in the modern era have been covert and conducted beneath the radar. Where they have been proclaimed publicly, they have tended to target non-state actors operating in militias or militant groups like Islamic State.

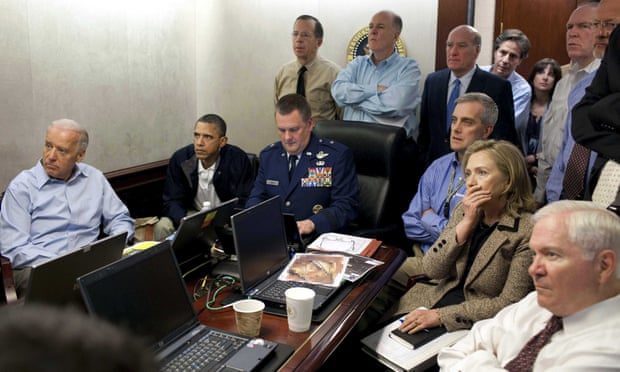

Barack Obama and Trump both claimed huge public relations victories when they oversaw the killings of Osama bin Laden and the Isis leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, respectively.

In 2008, the CIA worked hand in glove with the Israeli intelligence service the Mossad to target Imad Mughniyah, a senior Hezbollah leader, for assassination. In the course of their efforts they had the chance of taking out not only Mughniyah but also Suleimani in a single drone strike. In the end, the operation was called off because the US government blocked it on grounds that it could seriously have destabilised the region.

Despite such reticence, Mary Ellen O'Connell, a professor of international law at the University of Notre Dame, draws a direct line between earlier US administrations and the convention-shredding unpredictability of Trump. She said the advent of the unmanned drone in 2000 put the US on a slippery slope towards the current crisis.

The first deployment of a drone as an assassination tool was ordered by Bill Clinton in an effort to get Bin Laden. The first successful "targeted killing", as it is now called, came soon after, carried out by the Bush administration in Yemen.

Obama inherited Bush's widespread use of drone killings and increased their frequency tenfold, while seeking to give them a veneer of legal respectability with the secret internal "targeted killing memos". Those documents argued that drone assassinations were justified under international law as self-defense against future terrorist attacks - a rationale that has been widely disputed as a misreading of the UN charter.

"Since Obama there has been a steady dilution of international law," O'Connell said. "Suleimani's death marks the next dilution - we are moving down a slope towards a completely lawless situation."

O'Connell added that there was only one step left for the US now to take. "To completely ignore the law. Frankly, I think President Trump is there already - his only argument has been that Suleimani was a bad guy and so he had to be killed."

Comment: See also: