The Plague of Justinian, also known as the Justinianic Plague, first reached the Byzantine Empire around the year 541 and spread to North Africa and Western Europe. Caused by Yersinia pestis, the same bacterium responsible for Black Plague, this plague would continue to recur in parts of Europe up to the mid-eighth century.

Accounts of the plague are dominated by the writings of Procopius, a Byzantine scholar who lived in Constantinople when the pandemic broke out. His narrative tells a story where the plague was catastrophic. For example, he writes:

Now the disease in Byzantium ran a course of four months, and its greatest virulence lasted about three. And at first the deaths were a little more than the normal, then the mortality rose still higher, and afterwards the tale of dead reached five thousand each day, and again it even came to ten thousand and still more than that. Now in the beginning each man attended to the burial of the dead of his own house, and these they threw even into the tombs of others, either escaping detection or using violence; but afterwards confusion and disorder everywhere became complete. For slaves remained destitute of masters, and men who in former times were very prosperous were deprived of the service of their domestics who were either sick or dead, and many houses became completely destitute of human inhabitants. For this reason it came about that some of the notable men of the city because of the universal destitution remained unburied for many days.

Comment: As noted in the comments below, outbreaks of plague weren't solely reported by Procopius.

Historians have usually followed Procopius' lead in explaining that plague was very destructive. It has been estimated that the mortality rate for the pandemic was between 33% and 60% in the Mediterraenean region, with as many as 100 million people dying,

However, Lee Mordechai and Merle Eisenberg, writing in the journal Past and Present, have offered a new look at the Plague of Justinian, and they reassess its impact. They write that:

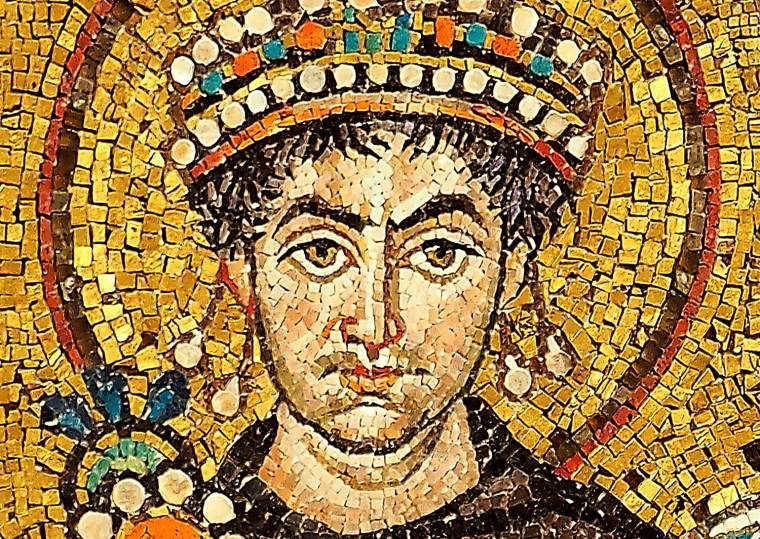

... the plague was geographically vast and caused high mortality in some cases. On a number of occasions, it had a devastating short-term effect. However, we argue that the effects of the plague were neither uniform, nor so catastrophic as to cause substantial mortality at the societal level, not to mention the collapse of states or empires. Without disregarding the suffering of the many victims of plague, the available evidence suggests that any direct mid- or long-term impacts of plague on the societies or the population of the Mediterranean world were minor.Their article looks at the various sources, including literary and archaeological records, and points out flaws in its evidence. For example, Procopius' account could have been exaggerated as part of his efforts to discredit and demonize Emperor Justinian and his rule. Moreover, other contemporary accounts of the plague that struck in 541-42 are much less verbose, with many of them briefly noting that it was among a number of other natural disasters that happened during this period. The authors conclude that 'most existing references in the literary sources are general and vague. In all accounts, plague quickly disappears and multiple sources gloss over it."

When it comes to archaeological research, Mordechai and Eisenberg note this "provides an underwhelming case for the plague's mortality." The burials from the period find few cases of people who were infected by plague. For example, at two major burial sites in Germany - Aschheim and Altenerding - where close to 2000 graves have excavated from this period, they have only been able to confirm in eleven cases that a person had the Yersinia pestis bacterium.

Looking at other types of evidence, the scholars spot other problems. They write:

Our investigation of prosopographical data found eight individuals out of several thousand who can be said to have perhaps died of plague. Tracing these individuals back to the original sources reveals that plague actually seems to have killed only two, and potentially another three, people. Regardless, none of these eight people died during the first outbreak, which was supposedly the deadliest.Mordechai and Eisenberg believe that much more research, especially archaeological, is needed before we can come to conclusions on how widespread and destructive the Plague of Justinian actually was. They caution that historians should not try to use the epidemic as the catalyst for widespread changes in the Byzantine Empire and late Roman world that took place in the sixth to eighth centuries.

They conclude:

This article has aimed to stimulate the scholarly discussion of the Justinianic Plague. Building upon primary studies and recent research, it rejects the current scholarly consensus of the maximalist interpretation of plague. Despite the many challenges involved, the potential to understand the Justinianic Plague is greater today than ever before. It is only through joint effort and a critical approach that we could hope to answer the pressing questions involved in this subject.

The article "Rejecting Catastrophe: The Case of the Justinianic Plague," by Lee Mordechai and Merle Eisenberg, appears in Past and Present, Volume 244, Issue 1 (2019). You can access it from Oxford University Press.

Comment: Perhaps part of the problem lies with a lack of understanding of just how many died because of other events, such as famine, flooding, earthquakes, and so on. What is clear is that the period was racked with disaster:

- 536 AD: Plague, famine, drought, cold, and a mysterious fog that lasted 18 months

- Plague and climate change devastated fading Byzantine empire

- Did cometary catastrophes cause the Justinian Plague and end the Roman Empire?

- Comets and the early Christian mosaics of Ravenna

- History textbooks contain 700 years of false, fictional and fabricated narratives

And for Precopius' fascinating insight into Justinian's rule, see: Truth or Lies Part 8 Procopius: Secret HistorySee also:

- Book Review: New Light on the Black Death by Mike Baillie

- New Light on the Black Death: The Viral and Cosmic Connection

- Just two plague strains wiped out 30%-60% of Europe

- Black Death traced back to Russia's Volga region via ancient DNA

Also check out SOTT radio's Behind the Headlines: Who was Jesus? Examining the evidence that Christ may in fact have been Caesar! for more details on the preceeding events and the tumult that continued for at least a century. From the transcript: