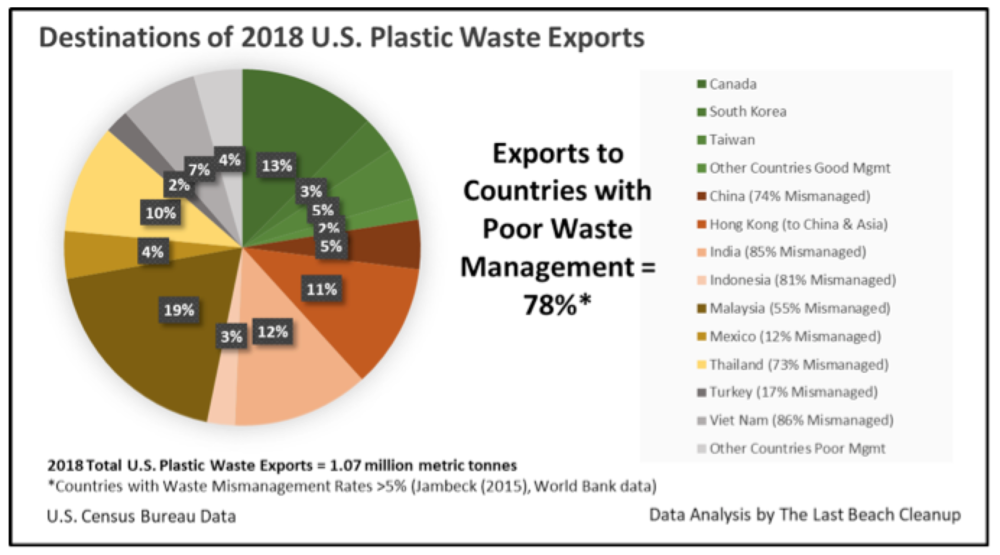

The U.S. Census Bureau recently published complete 2018 export data for shipments of plastic waste (officially called "waste, paring and scrap") generated in the U.S. and sent to other countries. As shown in Figure 1, 78% (0.83 million metric tonnes) of the 2018 U.S. plastic waste exports were sent to countries with waste "mismanagement rates" greater than 5%. That means about 157,000 large 20-ft (TEU) shipping containers (429 per day) of U.S. plastic waste were sent in 2018 to countries that are now known to be overwhelmed with plastic waste and major sources of plastic pollution to the ocean. The actual amount of U.S. plastic waste that ends in countries with poor waste management may be even higher than 78% since countries like Canada and South Korea may reexport U.S. plastic waste. The data also indicates that the U.S. continued to export about as much plastic waste to countries with poor waste management as we recycle domestically [1].

Plastic pollution activists and the chemical and plastic product industries commonly agree that countries without secure waste management systems are not currently equipped to safely and sufficiently manage plastic waste. So why is the U.S. still adding to the problem by shipping our plastic waste to those countries?

Numerous investigations have exposed that plastic waste exports have been crudely processed in unsafe facilities and have created pollution and social harms in the receiving countries. While some countries are starting to restrict plastic waste imports, the flow of plastic waste to countries with high waste mismanagement rates continues with 49 million kg (9,173 TEU containers) shipped in December 2018. There are compelling reasons for the U.S. and other countries to stop exporting plastic to these countries, including reducing plastic pollution to the ocean, increasing the focus on development of domestic waste management and recycling systems in the importing countries and spurring solutions in the U.S. to responsibly address our plastic use and waste. The U.S. should follow the lead of the United Kingdom (U.K.), where there is a bill before Parliament, to end plastic waste exports to countries with poor waste management systems and not wait for those countries to refuse our waste.

Plastic Waste Exports Have Been Shipped Off and Counted as Recycled for Decades

Plastic waste has been exported and counted as "recycled" by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and the waste and recycling industry for decades. The U.S. Census Bureau data shows exports to China and other countries dating back to 1992, the first year in the database. Without documented traceability of the final fate of the plastic waste, bales of waste plastic collected from municipal and commercial recycling systems were loaded onto trucks and shipped to buyers in foreign countries, many of which had inexpensive labor, no health and safety standards, few environmental regulations and no guarantee that the plastic waste would actually be recycled. The Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) publishes a Scrap Specifications Circular which provides detailed specifications for scrap plastic materials as a basis for certifying scrap quality and valuation for buyers and sellers. It does not, however, address requirements or assurance for recycling facilities receiving scrap plastic.

While a review of the credibility of the final recycling facility destinations of U.S. plastic waste has not been found, the U.K.'s National Audit Office criticized the rigor of the U.K.'s Environment Authority (EA) oversight of plastic waste exports in 2018. The EA is now investigating allegations of U.K. plastic waste exports being left to leak into rivers and the ocean in destination countries.

U.S. plastic waste exports have declined by nearly half between 2015 and 2018 (from a high of 2.05 million metric tonnes to 1.07 million metrics tonnes). The primary reason for the decline is China's strict scrap import policies which have reduced imports of plastic waste from the U.S. with a reduction of 96% since its peak in 2012. The decline is positive news for the ocean, rivers, ecosystems and the people of the receiving countries and world: less plastic waste was sent to places that do not have secure waste management systems such that all of the plastic waste will be responsibly recycled into new plastic products.

Exposed: Plastic Waste Creates Plastic Pollution and Social Harm in Importing Countries and the Ocean

The documentary "Plastic China" by Wang Jiuliang debuted in China in 2014, exposing the environmental and social harm caused by plastic waste imported by China. The film premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in November of 2016, and was shown at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. It is available online for viewing in the U.S. on Amazon. Some waste experts believe that the documentary was a motivation for China's strict National Sword regulations to end China's unofficial role as the world's "dumping ground" for waste.

China's strict plastic waste import regulations have done more than reduce environmental and social harms within the country. The National Sword has exposed the fallacy and flaws of the international flow of plastic waste exports as a responsible method of recycling plastic and creating a so-called "circular economy" of plastics.

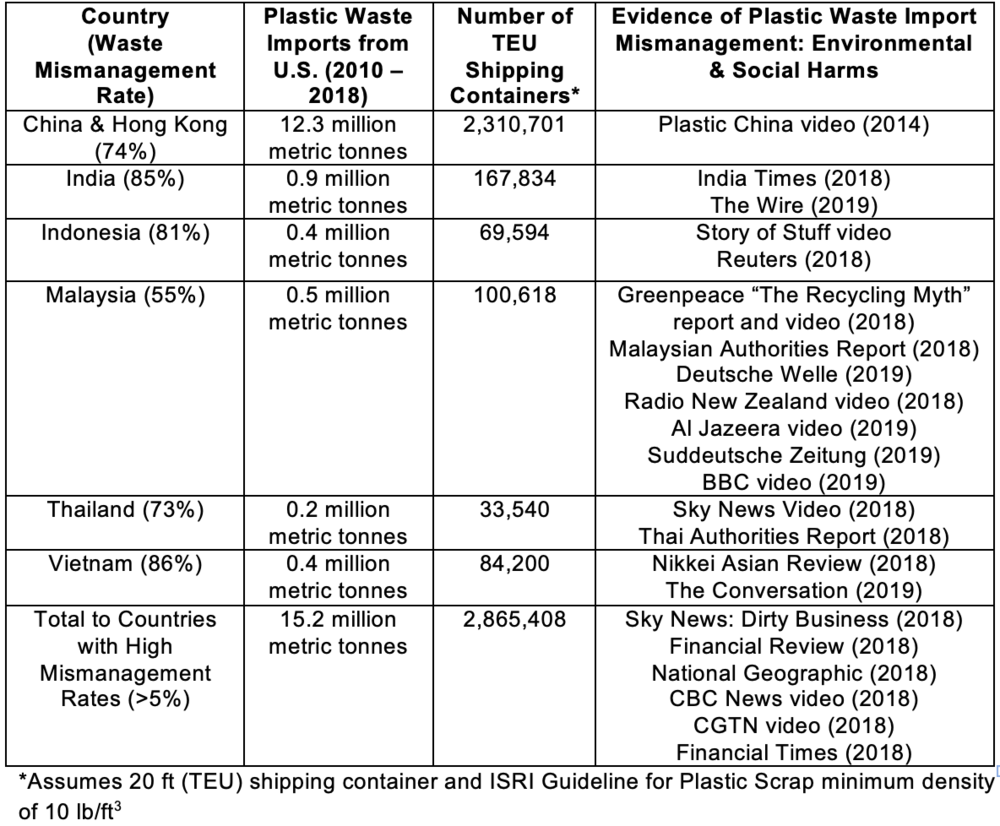

As summarized in Table 1, additional documentaries and reports have shown similar environmental and social harms of plastic waste exports to other countries.

The Conversation reports that in Vietnam "more than half of the plastic imported into the country is sold on to "craft villages", where it is processed informally, mainly on a household scale. Informal processing involves washing and melting the plastic, which uses a lot of water and energy and produces a lot of smoke. The untreated water is discharged to waterways and around 20 percent of the plastic is unusable so it is dumped and usually burnt, creating further litter and air quality problems. Burning plastic can produce harmful air pollutants such as dioxins, furans and polychlorinated biphenyls and the wash water contains a cocktail of chemical residues, in addition to detergents used for washing. Working conditions at these informal processors are also hazardous, with burners operating at 260-400℃. Workers have little or no protective equipment."

The evidence in the documentaries and reports clearly and credibly shows that plastic waste shipped to these countries should not all be counted as "recycled" as is common practice by the U.S., U.K., European Union (E.U.), Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Plastic waste exports should also not all be counted as "recycled" by companies who are promoting the circular economy scheme to defend their single use plastic products.

Asian Countries Taking U.S. Plastic Waste Blamed for World's Ocean Plastic Pollution

In 2016, before China's National Sword restrictions were implemented, University of Georgia waste experts estimated that plastic waste imports added another 10.8 percent to the plastic waste China generated domestically, an additional 7.4 million metric tonnes on top of the 60.9 million metric tons of domestic plastic trash created in China that year.

At the same time that the U.S. and other countries have been exporting plastic waste to Asian countries which are ill-equipped to manage it, those same Asian countries are being blamed as the leading polluters of plastics to the ocean. This editorial on Earth Day 2018 from the Deputy Editorial Director of the USA Today tells Americans not to feel guilty about our plastic trash because "Asian countries and messy fisherman are destroying the world's oceans". U.S. chemical, plastics and consumer product companies highlight Asian countries as the major source of ocean plastic pollution in their industry-funded "Stemming the Tide" report from 2015, while recognizing that there are insufficient plastic waste management systems in those countries.

Reasons to End Plastic Waste Exports to Countries with Poor Waste Management Systems

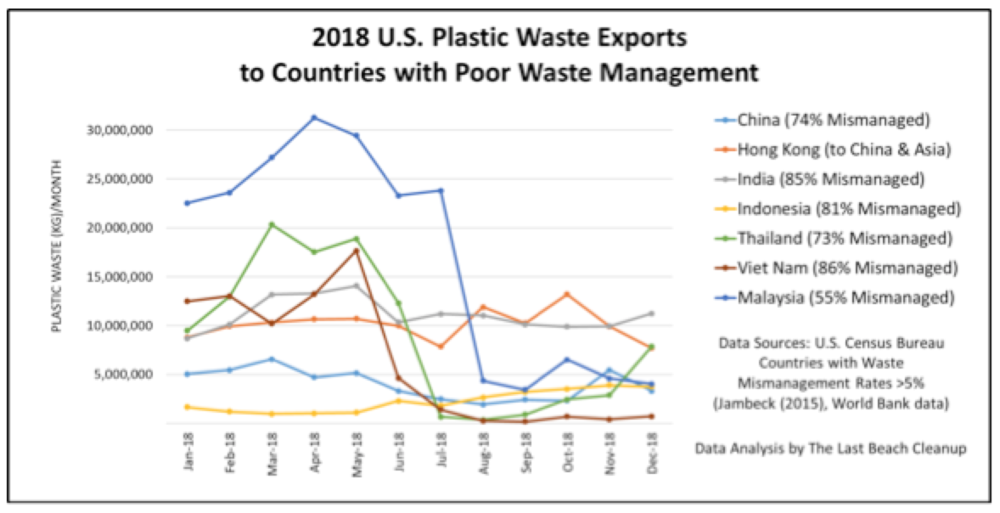

Governments in Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, concerned by the flood of imported plastic waste into their ports in the first half of 2018 and pushed by citizens like Daniel Tay in Malaysia, are beginning to place restrictions on imports of plastic waste. Figure 2 shows declines in U.S. plastic waste exports to two countries (Malaysia and Vietnam) from monthly highs in mid-2018. The declines are partly due to government-induced import restrictions and partly due to congestion in ports and existing recycling facilities from the increased shipments in the first half of the year.

But firm and effective bans are not yet in place and the end of plastic waste imports is not certain. Local businesses in some countries, who would prefer cheap plastic waste imports instead of investing in their own country's waste and recycling system, are fighting against the proposed plastic waste import restrictions. In Indonesia, the plastics industry is pushing to overturn restrictions on plastic waste imports, which were introduced in June 2018. As shown in Figure 2, plastic waste imports in Indonesia continue to increase from the U.S. The export of plastic waste to Thailand more than doubled between November 2018 (2.9 million kg) and December 2018 (7.9 million kg). According to Resource Recycling, "Asian buyers, including those in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, are now back and knocking on doors to purchase North American bales".

Beyond legal exports, reports of rising illegal plastic recycling factories in Malaysia and "traders fudging paperwork to skirt import limits" indicate that import restrictions may not be respected as "some exporters in the U.S. and elsewhere, and their importing counterparts in the destination countries, are reportedly falsely identifying scrap plastic as another product in shipping paperwork", according to recycling industry journal Resource Recycling. In Malaysia, Suddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) reports that "people complain that the state does not enforce its own rules. They have little faith in the authorities. Two SZ inquiries to the relevant ministry in January (2019) remained unanswered, so there is no official information, whether the import ban imposed in the fall actually affected all deliveries from abroad". In February 2019, a Malaysia official noted that 139 illegal plastic recycling operators had been found, that they quickly move from one location to another and stated "Wherever there is a port, you will have the import of plastic waste".

Figure 2: Destination of 2018 U.S. Plastic Waste Monthly Exports (U.S. Census Bureau data) and Country Waste Mismanagement Rates (Jambeck, 2015).

The evidence of plastic waste mismanagement and continuing high waste mismanagement rates shows that recycling of imported plastic waste has not led to creation of a strong domestic waste management system in destination countries. Beyond reducing plastic pollution in importing countries, ending plastic waste exports will provide benefits to the destination countries by spurring investment and local employment in waste and recycling systems in their domestic markets. Funding from international and in-country government sources is growing for improvement in countries with high waste mismanagement rates. To reduce plastic pollution and improve waste management system infrastructure and operation in the countries, it is critical that the funding be invested in improving domestic waste systems, not recycling businesses for imported waste.

Ending plastic waste exports to countries with poor waste management will also benefit the U.S.:

- We will have a clearer picture of our plastic waste generation volume. That will drive reduction in the generation of low value single-use plastic waste that is economically unrecyclable and commonly polluted, like single use polyethylene bags, expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam food containers and plastic straws. City and state laws are spreading across the U.S. now to restrict free distribution of these items to prevent plastic pollution and reduce waste to landfills. New Jersey and Vermont have proposed plastic pollution "trifecta" legislation to reduce waste generation from plastic bags, straws and EPS foam food containers.

- The need for legislation to strengthen U.S. recycling systems to recover higher value plastic will become evident. As detailed in a recent Plastics News article, a plastics recycling expert has calculated that container deposit laws are required across the U.S. to increase PET beverage bottle recycling above 40% from the current rate of about 29%. Washington State's proposed Plastic Packaging Stewardship legislation requires extended producer responsibility (EPR) to develop local recycling infrastructure which has been neglected because of the cheaper option of exporting plastic waste.

- Reduction of plastic pollution in the ocean that causes many harms to human, ecosystem and marine health and economic and social costs will benefit Americans.

States and Cities Can Lead, If U.S. Commerce Department Will Not

The U.S. Federal Government can restrict plastic waste exports via Commerce Laws as is done for some types of electronic waste, but is not expected to in the near future. Instead, U.S. cities and states can follow Washington State's proposed Plastic Packaging Stewardship legislation and employ their legal rights to require that "plastic packaging exported for recycling is managed in an environmentally sound and socially just manner at facilities operating with human health and environmental protection standards that are broadly equivalent to those required in the United States" to ensure that U.S. plastic waste does not directly contribute to plastic pollution in other countries. Cities can also follow Palo Alto's new waste management contract model that requires the contractor to track the final destination of waste and assess environmental and human-rights violations in the final destinations. The city retains the option of directing the contractor to use different waste purchasers if any environmental and social issues are identified.

If we are serious about ending plastic pollution to the ocean, the U.S. must stop exporting our plastic waste to countries that we know are ill-equipped to manage it.

Jan Dell, PE, is an Independent Engineer on a Quest to The Last Beach Cleanup. Jan has worked with companies in diverse industries to implement sustainable business and climate resiliency practices in their operations, communities and supply chains in more than 40 countries including throughout Asia. Appointed by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, Jan was a member of the U.S. Federal Committee that led the 3rd National Climate Assessment from 2010 to 2014 and the Vice Chair of the U.S. Federal Advisory Committee on the Sustained National Climate Assessment in 2016-2017.Send her an email here.

Countries, where the leaders consider the US pissing on them as rain.

Shalom