A long-standing idea about the ancient Maya is that for most of the civilization's 700-year-long Classic period, which lasted from 250 to 950 A.D., warfare was more or less ritualized. Perhaps the royal family might be kidnapped, or some symbolic structures torn down, but large-scale destruction and high numbers of civilian casualties were supposedly rare.

Researchers have generally believed that only towards the very end of the Classic period, increasing droughts would have reduced food supplies, in turn escalating tensions between Maya kingdoms and resulting in violent warfare that is believed to have precipitated their decline. Research presented today in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, however, is adding to the evidence that violent, destructive warfare targeting both military and civilian resources (often referred to as "total warfare") was taking place even before a changing climate imperiled Maya agriculture.

"Due to the steep surrounding landscape, sediment accumulated in this lake at the rate of about 1 cm [approximately 0.4 inches] every year," he explains, "providing us with high-resolution information of what was going on in the area." Fast-accumulating sediment indicates that forests were cut and land was cleared, causing increased erosion, while corn pollen found in those sediments leave no doubt about the main crop grown in the area. Yet the most remarkable thing Wahl found at the bottom of Laguna Ek'Naab was a 1.2-inch-thick layer comprised of large chunks of charcoal.

Wahl's first expectation was that the large fire that likely produced all this charcoal — and the decline in corn pollen seen in deposits formed in the decades and centuries after the fire occurred — might have been due to the Terminal Classic-era droughts the paleoclimatologist was interested in studying. Yet for the earlier Classic period in which the charcoal entered the lake — radiocarbon-dated to between 690 and 700 A.D. — there was no evidence of drought.

Comment: It seems the century preceding this date was a particularly troubled time for much of the planet: 536 AD: Plague, famine, drought, cold, and a mysterious fog that lasted 18 months

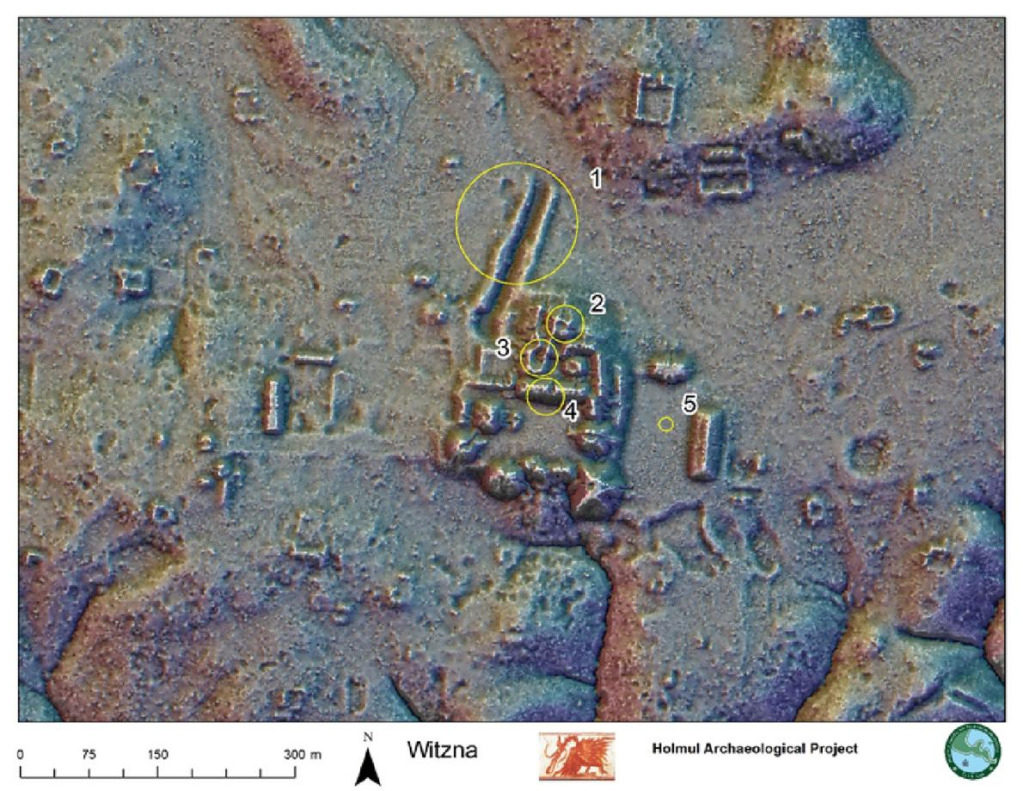

While Wahl was still trying to make sense of this discovery, a team of archaeologists led by National Geographic Explorer Francisco Estrada-Belli of Tulane University started their first dig of Witzna, a site that was initially discovered in the 1960s, but never explored in depth. As they gradually uncovered what was left of the buildings, they found that many of them had been intentionally damaged or destroyed, and traces of fire were all around, suggesting the fire may instead have been an intentional one lit by enemy invaders. They also found something quite rare: an inscription clearly stating the name the ancient Maya gave the city: Bahlam Jol. (The Maya name of many cities remains unknown.)

The scientists contacted Alexandre Tokovinine, an expert in Maya writing at the University of Alabama, who recalled an inscribed stone monument discovered in the nearby city of Naranjo that documented a series of successful military campaigns against neighboring kingdoms. When Tokovinine compared the inscriptions, he realized that part of the Naranjo inscription stated that on a date reconstructed as May 21, 697, "Bahlam Jol burned."

"This is right at the time when the charcoal was shown to have accumulated in the lake," says Wahl, "allowing us to confidently link the description to the actual fire."

Surprisingly, Bahlam Jol was far from the only city proudly proclaimed in the Naranjo monument to have "burned". The same thing happened to at least three other cities in the area, including one known today as Buenavista del Cayo, where researchers have recently also found evidence of large-scale fires. To Wahl and his coauthors, including Estrada-Belli, this suggests it is very unlikely that total warfare only emerged about a century later in the Terminal Classic period.

This suggests the difficulty to grow food due to a changing climate may have been an important driver of the Maya's decline even if it didn't do so by escalating warfare. Wahl's study adds to a recent and growing body of evidence showing that violent warfare existed long before the Terminal Classic period.

As Takeshi Inomata of the University of Arizona, who has done research on pre-Columbian warfare himself but was not involved in this study, points out, "There is an increasing understanding that there were destructive wars throughout the Classic period, which may have resulted in declines in population numbers and economic activities." He adds that there probably were certain restrictions on warfare, however, as there are today. "So instead of making categorical statements, we need to trace specifically how warfare changed through time," Inomata says.

Archaeologist James Brady of California State University in Los Angeles, who has worked on different projects across the region but was also not involved in this study, calls the new data "interesting and provocative.

"I was never convinced that warfare before the Terminal Classic period was only ritualized," he says. "It must have been a fact of life from a very early time, and it often had serious consequences."

If climate and weather, vulcanism and tectonic activity is in fact electrical within a Solar (and Galactic) capacitance then the charge differentials of planetary of cometary instabilities are the destructive element - as in Tunguaska.

Scottish hill forts petrified.... Scottish Crannocks (man made loch islands) constructed.... Connected?

Or on larger scales Sodom and Gomorrah - or indeed look at Andy Hall's work on Plasma Geology (Thunderbolts.info).

Ironically the time of Terror has passed - but human consciousness has been 'terraformed' along with the Earth and re-enacts a catastrophic past in destructive wars and toxicities in the drive for possession and control. While manipulators hack apocalyptic guilt and fear to generate priesthoods of power who sacrifice people in a more systemic, pervasive and industrial scale.