© Rose Wong

Tired: Shallow work. Wired: Deep work.Here's what my browser generally looks like: work email in the left-most tab, always open. TweetDeck in the next one, always open. A few Google Docs tabs with projects I'm working on, followed by my calendar, Facebook, YouTube, this publication's website and about 10 stories I want to read - along with whatever random shiny thing comes across my desktop. (Not to mention my iPhone constantly nagging me,

though I've mostly fixed that problem.)

This is no way to work! It's awful, and my attention is divided across a dozen different things. My situation is far from unique, and most people who do most of their work on a computer know it all too well.

Enter "deep work," a concept coined by one of my favorite thinkers in this space, Cal Newport.

He published a book in 2016 by that name, and in it he details his philosophy and strategy for actually focusing on the things we can do and accomplish.

This week I've invited Cal, whose new book,

Digital Minimalism,

comes out next month, to talk about how to do deep work, why it matters and how we can use it in our lives.

Tim Herrera: Hey, Cal! Thanks so much for chatting with me this week. For those who don't know: What exactly is deep work?

Cal Newport: Deep work is my term for the activity of focusing without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. It describes, in other words, when you're really locked into doing something hard with your mind.

TH: So, like, closing your email tab or putting your phone in a drawer?

CN: Right.

In order for a session to count as deep work there must be zero distractions. Even a quick glance at your phone or email inbox can significantly reduce your performance due to the cost of context switching.TH: You use a term in your book to describe that feeling:

attention residue. What exactly do you mean by that, and what's the reason for it? Is there a way to actually avoid it?

CN:

Every time you switch your attention from one target to another and then back again, there's a cost. This switching creates an effect that psychologists call attention residue, which can reduce your cognitive capacity for a non-trivial amount of time before it clears. If you constantly make "quick checks" of various devices and inboxes, you essentially keep yourself in a state of persistent attention residue, which is a terrible idea if you're someone who uses your brain to make a living.TH: You outline the four rules of deep work in your book, which I think is a great place to start for someone who's just learning about these ideas. Let's go through them. What is the first rule of deep work, and how do I apply it to my life?

CN: The first rule is to "work deeply." The idea here is that if you want to successfully integrate more deep work into your professional life, you cannot just wait until you find yourself with lots of free time and in the mood to concentrate. You have to actively fight to incorporate this into your schedule. It helps, for example, to include deep work blocks on my calendar like meetings or appointments and then protect them as you would a meeting or appointment.

TH: And that has a lot to do with habit formation vs. willpower, too, right?

CN: Right.

Deep work is demanding, and our brains, which are evolved to avoid unnecessary energy expenditure, therefore try to avoid it if possible. We're simply not evolved to give concentration the same priority that we might give to evading a charging lion. Therefore, you cannot rely on willpower alone. You need all the help you can get to trick yourself into getting started with this activity.TH: So, great, we've got a strategy to build habits around deep work and to actually do it. What's rule two?

CN: The second rule is to "embrace boredom."

The broader point here is that the ability to concentrate is a skill that you have to train if you expect to do it well. A simple way to get started training this ability is to frequently expose yourself to boredom. If you instead always whip out your phone and bathe yourself in novel stimuli at the slightest hint of boredom, your brain will build a Pavlovian connection between boredom and stimuli, which means that when it comes time to think deeply about something (a boring task, at least in the sense that it lacks moment-to-moment novelty), your brain won't tolerate it.TH: Which is a perfect segue into your third rule of deep work.

CN: The third rule is to "

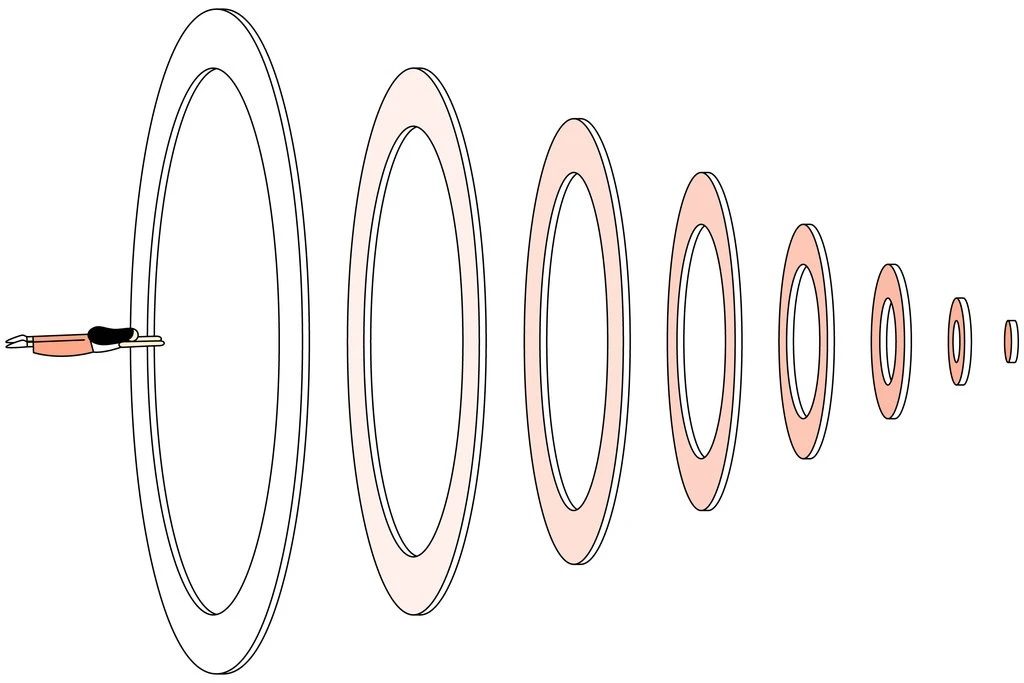

quit social media." The basic idea is that people need to be way more intentional and selective about what apps and services they allow into their digital lives. If you only focus on possible advantages, you'll end up, like so many of us today, with a digital life that's so cluttered with thrumming, shiny knots of distraction pulling at our attention and manipulating our moods that we end up a shell of our potential. In "Deep Work," I introduced this idea mainly to help professionals protect their ability to focus, but it hit a nerve, and eventually evolved into the popular digital minimalism movement that I've been writing about more recently.

For example, I've never had a social media account, and though I may have missed out on various small advantages here and there, I'm convinced that it has had large positive impacts on my professional output and personal satisfaction.TH: Which brings us full circle to your final rule of deep work: "Drain the shallows." What does that mean, and how do we do it?

CN: "Shallow work" is my term for anything that doesn't require uninterrupted concentration. This includes, for example, most administrative tasks like answering email or scheduling meetings.

If you allow your schedule to become dominated by shallow work, you'll never find time to do the deep efforts that really move the needle. It's really important, therefore, that you work to aggressively minimize optional shallow work and then be very organized and productive about how you execute what remains. It's not that shallow work is bad, but that its opposite, deep work, is so valuable that you have to do everything you can to make room for it.TH: That's perfect. I'm taking this to be permission to ignore all of my emails, and now I'm going to go delete my Twitter. Thanks so much for chatting, Cal. Any last words on how we can make deep work

work in our lives?

CN: When it comes to topics like distraction in the workplace, my philosophy is that instead of focusing too much on what's bad about distractions, it's important to step back and remember what's so valuable about its opposite.

Concentration is like a super power in most knowledge work pursuits. If you take the time to cultivate this power, you'll never look back.

My grandfather complained about his middle school students not knowing how to work. 1947. Beneath that is the ability to stay intensely focused on a specific task in the context of a desired goal. His students had trouble with it because their fathers had largely gone to fight the war to end all wars, and if they came home were mutilated physically and emotionally. They were unable to properly nurture their children.

This article is indicative of what happens when fathers are ripped, by economic or legal conditions beyond their control, from the society of their children.