The news headlines are what caught Stephen Midway's attention. It all seemed so unusual to him.

Researchers would later chalk it up to especially warm water off the coast of North Carolina during that summer in 2015, or, in some cases, to an unusual distribution of tasty fish, or to the fact that more people went to the beach that year.

Whatever it was, one thing was clear: the sharks were out, and they seemed to be nipping people at a higher rate than usual.Curious about it, Midway, an oceanography professor at Louisiana State University, decided to partner with scientists at the University of Florida to embark on a research project to figure out if the seemingly rising number of shark bites were statistically important. It started as a question local to the US but morphed into a project that is the first of its kind to look at shark attacks on a global level across a half-century.

Their work was

published this week (Feb. 27) in the journal

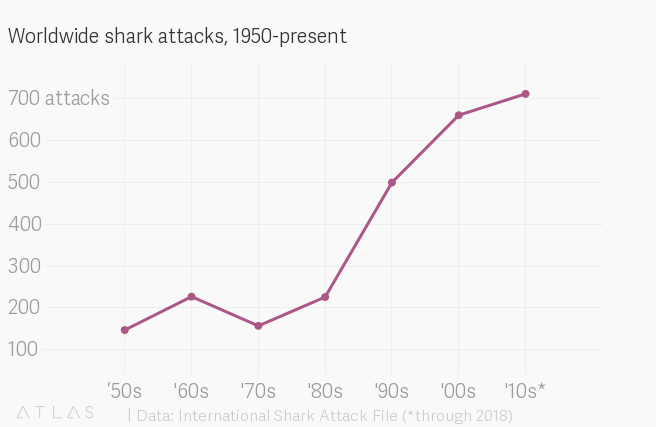

PLOS One. It shows the number of global shark attacks are on the rise, but the risk of being bitten by one of the seafaring predators—despite the occasional smattering of alarming news headlines—remains extremely low. To be sure, the number of attacks haven't increased every consecutive year (between 2017 and 2018 the number decreased),

but generally they do. The overall trend across the decades shows more people are being bitten by sharks.Midway and his team looked at shark attack data between 1955 and 2015 across 14 countries, focusing especially closely at the three countries that logged the most attacks: the US, Australia, and South Africa. What he found was that in some heavily-populated areas, where beachfront developments and tourism had sprouted and grown, attacks had as much as doubled. That was particularly notable in areas along the East Coast of the US and in Southern Australia.

In the US, the number of shark attacks increased from four people in 1955 to 57 in 2015, according to the Global Shark Attack File. In Australia it jumped from three to 23. The majority of countries saw no change, with most of them showing attacks at zero for most years across the six decades.

"With more people in the water, the chance for a shark attack increases," Midway says in a statement. "However, I must stress the fact that not all places across the globe saw an increase. And even in the places where we saw an increase, the chances were still one in several million."

Only a tiny portion, about 6% or less, of shark bites end in death, according to the research. The rest are charitably described by Midway as being akin to "dog bites." In the 55 years between 1960 and 2015, officials reported a total of 1,215 shark attacks in the US. Most were just nips and bites; only 24, or about 2%, were logged as fatal.

Midway says scientists need to learn more about sharks, why they go where they go, and what their regional trends are before anything definitive can be said about how to predict individual shark attacks, which right now is close to impossible.

The overall number of bites have been increasing in some areas over time.

Comment: Also pertinent is this recent January 2019 report which again points to an increasing trend in attacks: Fisherman killed by shark off Réunion Island - 23rd attack since 2011, with 10 fatalities

The above report is perhaps even more noteworthy because the large number of attacks that occurred were off a small island within a relatively short time frame.