In a forthcoming open-access article in the journal Analecta Romana, archaeologist and historian Steven Tuck of Miami University explains how his creation of a database of Roman last names led him to match up records from Pompeii and Herculaneum with records from the parts of Italy unaffected by the destructive power of Vesuvius. Tuck's goal in doing this work was not just to identify refugees but also "to draw conclusions about who survived the eruption, where they relocated, why they went to certain communities, and what this pattern tells us about how the ancient Roman world worked socially, economically, and politically."

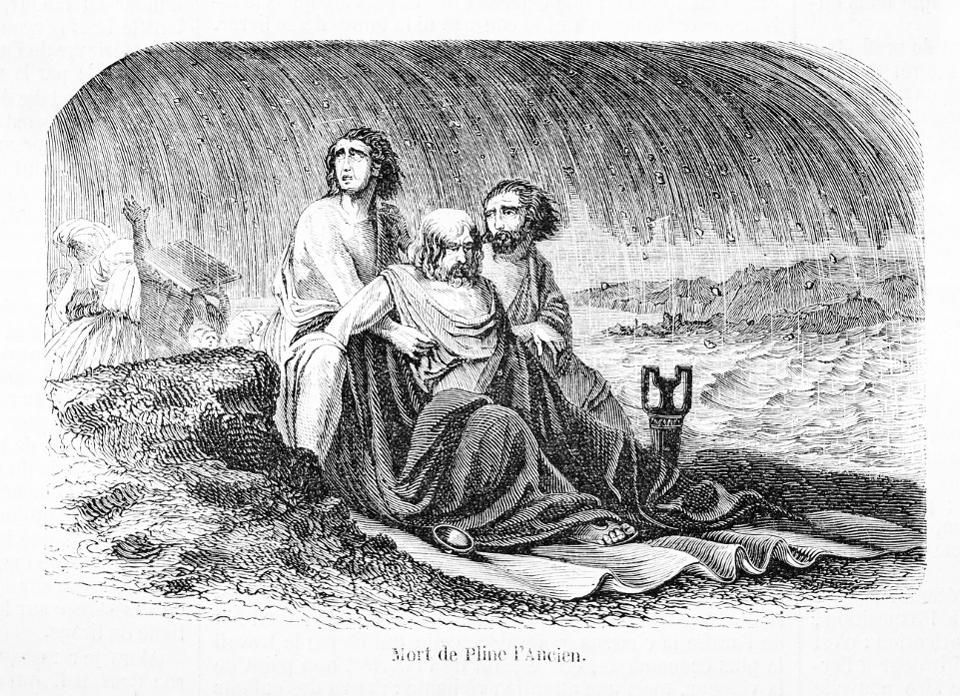

In order to find refugees, Tuck needed to investigate inscriptions on public buildings and tombstones, because historical records only emphasized the physical damage of disasters. This may seem odd to us today, as our news reports tend to center the loss of human life as the main result of a catastrophe, but in Roman times only a handful of narratives, such as Pliny the Younger's account of his famous uncle's death near Pompeii, reflect the human toll of these ancient natural disasters.

Tuck created a method for identifying refugees based on several lines of evidence, including: last names that were common in cities near Vesuvius and that show up elsewhere after 79 A.D.; specific inscriptions that list a person's origin at Pompeii or indicate they were born elsewhere; artifacts or cult objects characteristic of Pompeii or Herculaneum that were found in other places after the eruption; and new public infrastructure that may have been built to accommodate a refugee community.

"I looked for names at Pompeii that were prominent in the later years of the city and inscriptions that were as near as possible post-80 A.D. in the 'refuge communities'" elsewhere in Italy, Tuck explains. As an example, there are six people from the family Caninia known from 2nd century A.D. inscriptions at Neapolis (modern Naples). That last name appears earlier at Herculaneum but essentially nowhere else, suggesting the family moved because of Vesuvius.

Tuck makes an even stronger connection, though, for a particular member of this family: Marcus Caninius Botrio, whose name is recorded in the Album of Herculaneum. It is likely that Botrio "is the best surviving evidence of a specific individual from Herculaneum who resettled at Neapolis as a refugee, and then died there as attested by his tomb inscription," Tuck notes.

Another example Tuck presents comes from Roman Dacia, an area of the Empire that is now Romania and Serbia. On a tombstone there dated to 87 A.D., an inscription lists one Cornelius Fuscus, who was a citizen at Pompeii, lived at Neapolis, and was stationed in Dacia as a praetorian prefect who led five legions in Domitian's war. Fuscus "seems to have resettled from Pompeii to Neapolis after the eruption," Tuck concludes.

Tuck's combination of history and archaeology has produced strong evidence that it is possible to trace Vesuvian refugees. He finds that many refugees settled on the north side of the Bay of Naples, and that families tended to move together and then to marry within their refugee community. These people probably "represent either those who fled at the first sign of the eruption," Tuck says, "or those who were away from the cities when the eruption occurred." But while this method seems to work for identifying reasonably wealthy citizens, Tuck knows that it is limited because it cannot help him discover non-Romans, slaves, or migrants who escaped Vesuvius.

In the end, Tuck finds it important to note the Roman government's reaction to Vesuvius. While in the contemporary U.S., our governors or president immediately declare a state of emergency and work to help people affected by a natural disaster, the Roman government didn't react until after people were resettled. Once refugees had moved, though, the emperor earmarked money to build new infrastructure in communities like Naples and Pozzuoli to accommodate the influx of people.

"The evidence presented makes it clear that we can now answer the questions of whether anyone survived the eruption of Vesuvius from Pompeii and Herculaneum and where they resettled," Tuck concludes. "How many refugees escaped is a question that cannot be answered with any certainty; the evidence simply is not good enough to allow for anything like accurate counts."

Tuck's work, though, combined with bioarchaeological evidence from the skeletons of people who were trapped by Vesuvius, and with biochemical evidence in the form of isotope and ancient DNA analysis, paves the way for a fuller understanding of this catastrophic natural disaster and its ramifications on the Roman people.

Kristina Killgrove is a bioarchaeologist and science communicator. For more ancient news, follow her on Twitter (@DrKillgrove), Instagram (PoweredbyOsteons), or Facebook (Powered by Osteons).

Comment: See also:

- Pompeii: Newest find shows man decapitated by rock during eruption of Vesuvius

- Exploded skulls and vaporized bodies: Pompeii finds reveal horror of Vesuvius eruption

- The destruction of ancient Rome - The barbarians were not responsible

And for more on the disasters civilizations have endured, check out SOTT radio's: Behind the Headlines: Who was Jesus? Examining the evidence that Christ may in fact have been Caesar!