When British forces pull down the union jack for the last time in Afghanistan this year, it will be a hugely symbolic moment. It is not just that the departure marks the end of 13 years of British involvement in combat in that troubled country. The surprise is that it could also signal the end of a century or more of unbroken warfare by British forces.

Comment: It didn't. 'ISIS' suddenly arrived on the scene in Syria, then Iraq, and British soldiers were back in 'expeditionary' mode...

Next year may be the first since at least 1914 that British soldiers, sailors and air crews will not be engaged in fighting somewhere - the first time Britain is totally at peace with the rest of the world.

Since Britain's declaration of war against Germany in August 1914, not a year has passed without its forces being involved in conflict. It is a statistic that has been largely overlooked, and not one about which the government is likely to boast.

Comment: Indeed. In the entire time since then the whole world has been daily informed (largely through anglophone media) about these dictators and those tyrants, but the backdrop - British and American warmongering - is so ubiquitous and monotonous that it's like white noise, or wallpaper no one notices.

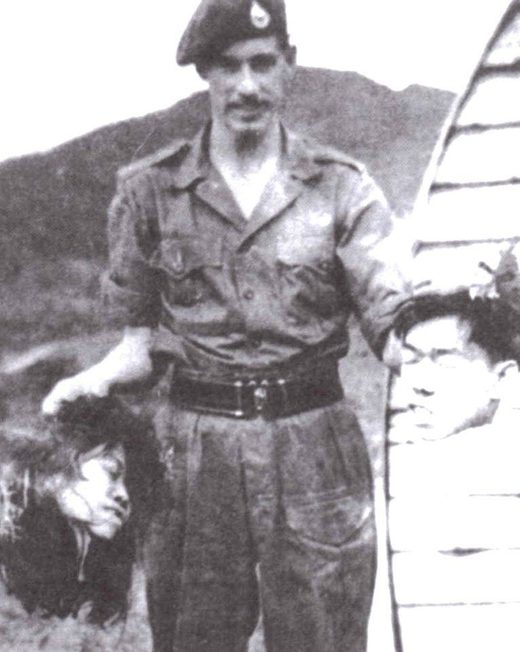

The past 100 years have seen two world wars, large-scale conflicts in Korea and Iraq, and small-scale actions in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. There have been punitive operations in defence of empire, cold war operations, post-9/11 support for the US, and the Troubles in Ireland.

No other country, even those with similarly militaristic traditions, has been engaged continuously over such a long span. Even during 1968, a year often hailed by members of the British armed forces and some military historians as a year of peace, there was fighting.

The timeline of constant combat may stretch even further back, given Britain's imperial engagements, all the way to the creation of the British army in 1707.

Britain's generals and politicians anticipate that 2015 may be a year finally without conflict and are planning accordingly. Senior military staff describe this as a "strategic pause".

Comment: They never left Afghanistan. About 500 (declared) soldiers remained, a number that has doubled every year since 2015. The UK is currently engaged in about 25 military operations in 30 countries. And that doesn't even begin to account for how many mercenaries in 'war theaters' are hired through British-registered, or British-controlled, firms.

Assuming agreement is reached with the Afghanistan government before the end of the year, a few hundred soldiers will be left behind to help with training at the army academy, and a few others in a consultative role but not for combat. Special forces could be deployed but no one in the Ministry of Defence is going to go public on that.

Comment: You have to hand it to British civil servants: their (ab)use of the English language is marvelous (in a devious sense).

The potential absence of war is attributed to a number of factors: lack of public support for the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts; cuts in the size of the army, making it harder to mount similar operations; an increasingly multicultural Britain that could make intervention in Muslim countries more problematic; and antipathy among the present generation of politicians to interventions, as demonstrated by last year's Commons vote against action in Syria.

Comment: Like any of that ever stopped the British from waging a nice little war.

A report by the International Institute for Strategic Studies this week showed Britain dropping from fourth place to fifth in the world in terms of budget spending on defence. The army is to be cut from 102,000 to 82,500 by 2018.

The former Labour defence secretary Lord Browne said: "The British public have made it clear that there is very little support for new expeditionary wars of choice, even where there is a national security dimension. They may tolerate long-range support of oppressed people, but intervention by UK troops is for now off-limits.

"The new generation of British politicians have taken note. They have seen their immediate predecessors' political capital drain away in times of war. In my view, there is a growing reluctance among them to allow the same thing to happen to their generation."

Read the rest here

Comment: 'War-weariness' is not a problem for the British elites: they can rely on media creating fictitious enemies (the Russians, currently).