In other words, can some varieties of evil be better understood in terms of spirit possession or obsession, rather than as a simple breakdown of neurochemistry in combination with subconscious drives?

I became more interested in this question after reading about the serial killer Charles Cullen, who, in his capacity as a nurse, murdered at least forty patients and probably many more. Throughout his life, Cullen made repeated suicide attempts, starting at the age of nine, when he drank chemicals from a chemistry set. After joining the Navy, he attempted suicide seven times before receiving a medical discharge. His first confirmed murders occurred a decade later, after which he attempted suicide on four occasions - three times in 1993 and again in 2000.

Now, it could be argued that these suicide attempts were not serious, since none of them succeeded. But at least some of them do appear to have been legitimate attempts at ending his own life. It's doubtful that, as a nine-year-old, he would have been sure that the chemicals he ingested would not prove fatal. And his last attempt, in 2000, was thwarted only because neighbors smelled the smoke coming from a charcoal grill he'd lit inside his apartment in the hope of poisoning himself with carbon monoxide.

At the very least, it appears that Charles Cullen was a deeply divided personality. On one hand, he murdered scores of people over a long period, with no apparent hesitation or remorse. On the other hand, he repeatedly tried to take his own life, as if he found his homicidal obsessions intolerable. Is this inner conflict rooted only in psychological or neurological dysfunction, or could it be indicative of an external personality trying to control and distort his behavior, and of his increasingly desperate attempts to escape?

The latter argument is in line with the position taken by Dr. Terence J. Palmer in a 2008 paper titled "Are They Evil, Mad or Possessed?" Palmer argues that "previous investigations have neglected important data due to an epistemology that is fundamentally physical and rationalistic." He focuses specifically on Dr. Helen Morrison's 2004 book My Life Among the Serial Killers.

Morrison, a forensic psychiatrist, interviewed more than eighty serial killers. She wrote:

I have found that serial murderers do not relate to others on any level that you would expect one person to relate to another. They can play roles beautifully; create complex, earnest performances to which no Hollywood Oscar winner could hold a candle. They can imagine anything. They can appear to be complete and whole human beings, and in some cases are seen to be pillars of society. But they are missing a very essential core of human relatedness.

Comment: That's a good description of psychopathy.

It is this "dark, barren core" (Morrison's term), this absence of normal human feeling, that Palmer interprets in spiritualist, rather than positivist, terms. He takes a close look at Morrison's descriptions of the killers she interviewed and finds alternative explanations for their psychology.

One of them, Richard Macek, "wanted to be more than he was" (Morrison's words). Palmer observes that this observation implies a duality in Macek, "one personality that was human and one that wasn't." Morrison's sole attempt at hypnotizing Macek ended in disaster with Macek "suffering severe emotional and physical trauma." As a result, she never used hypnosis again, which meant she had no means of uncovering any hidden memories and buried motivations. This approach tended to limit her to physicalistic explanations.

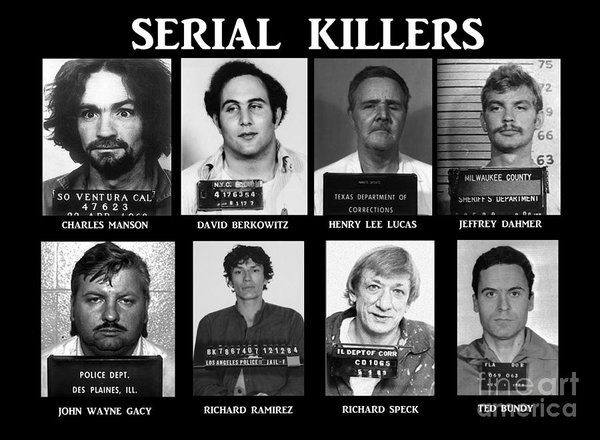

Morrison interviewed the sister of serial killer John Wayne Gacy. The sister recalled that Gacy once passed out after drinking too much, and when he came to, "he was like someone who was drunk, but he wasn't drunk. Something in his voice was different. It was not his voice." Palmer takes this story as additional evidence of a deep-rooted duality consistent with possession or obsession by an external personality.

Another killer often "appeared frightened for no reason, and his eyes darted about the room" (Morrison's words). Still another was so overcome by fear that at times he would run into his closet to hide for no apparent reason. Palmer writes:

It could be argued that at a deep unconscious level all serial killers are terrified of what possesses them, and an understanding of how we all protect ourselves from something mysterious and terrifying would shed much light on why some people become serial killers. To put this principle into ordinary everyday life, it is known that the bullied often becomes the bully.Some killers have heard voices ordering them to kill - usually a commanding, terrifying voice. Schizophrenia, or something more? Palmer notes that psychiatrists using so-called "spirit release" techniques have had some success in treating such symptoms. He cites the work of Alan Sanderson (a 2003 paper called "Consciousness as it Relates to the Nature of Psychiatric Disorder") and Andrew Powell ("The Contribution of Spirit Release Therapy to Mental Health"). A more familiar example may be Thirty Years Among the Dead, the famous 1924 book by Carl Wickland.

The killer Bobby Joe Long once spontaneously wrote "I am Darkness. I have always been." Morrison dismisses this writing as mere self-dramatizing hyperbole, but what if it was more than that?

Writing about the emotional immaturity of serial killers in general, Morrison asks:

Who, other than an infant, feels like he is controlling not just the world, but the universe around him? Who else but an infant feels so important that he thinks he is the center of the universe? And who else but a child would think in this way for no particular reason, not for wealth, not for power, not for human domination, but just to maintain and protect his own personal cosmos?"Palmer notes that true accounts of possession and exorcism written by M. Scott Peck and Malachi Martin indicate that "the emotional development of the subject was impaired by the possessing entity. The subjects were not able to grow emotionally and reach their true potential until they had been relieved of the possessing entity." Furthermore, an evil entity in touch with ultimate powers of darkness might well regard itself in such terms.

Not all medical practitioners reject the possession hypothesis. Dr Hans Naegeli-Osjord, writing in 1988, observed:

This phenomenon [of dissociative identity disorder, or multiple personalities] should not be viewed exclusively as possession or multiple personality, but [rather] some cases may be a result of dissociated personalities, while others are more likely to be cases of harassment by the spirit of a deceased person.... Both multiple personality and harassment should be considered when viewing the entire range of such disorders.... In cases of weakened ego and/or extreme stress, external entities may invade or harass the person to the point where counseling or treatment is indicated to enable the patient to return to a normal state.The killer Bobby Joe Long once dreamed that someone asked him if he believed in God. In the dream he replied that he did not. His interrogator then "went hysterical, pointing at me and laughing." Palmer notes:

We can perhaps see how Bobby Joe's demon had justification for his hysterical laughter. Bobby Joe in his rejection of a belief in God was in no position to have a belief in demons either, rendering him helpless and defenseless and holding himself responsible for his crimes.Palmer sees such dreams as "the soul of the serial killer ... expressing his fear and screaming out for help," a cry that Morrison missed because she simply assumed, on the basis of Long's absence of affect, that there was no emotional connection between Long and his dreams.

Comment: Morrison sounds like perhaps she just couldn't grok psychopathy. Perhaps there is nothing there to be afraid and "scream out for help". But then again, maybe that's what makes them good hosts, assuming such a thing is possible?

After watching a movie about the Boston Strangler, Long wrote to Morrison:

It was the most scary f-----g movie I ever saw. It was like watching ME in action. ... I remember him tying one to a bed and she started fighting. I had been through the same thing. I knew how the guy felt. Like a mirror. I swear. [The word "ME" is in all caps in the original]Morrison also noted that Long frequently complained about a strange feeling in his head, as if part of his head "had a kind of life of its own... Long said that something in his head and even in his body changed when someone close to him ... did him wrong." Long himself said:

It's similar to before I used to get into a fight, or just before I bust somebody's face. The anger. The blank thought. It's like I was void of thought. Like I left for a little while, then came back after.At one point he wrote to her in all caps:

IT'S NOT A GOOD FEELING TO KNOW MY LIFE IS OVER. TO KNOW THAT AT THE VERY BEST I'LL BE LOCKED UP LIKE AN ANIMAL THE REST OF MY LIFE. ALL BECAUSE I KILLED A BUNCH OF SLUTS AND WHORES AND I DON'T EVEN KNOW - WHY?Frankly, I don't know how much credence to place in the spirit-harassment hypothesis. I was fairly impressed with Wickland's pioneering study, but I haven't kept up with more recent work. As time permits, I intend to do more reading, starting with some of the links listed above. Other possible sources of information are Alan Sanderson's paper "Spirit Release in Clinical Psychiatry" and Terence Palmer's website.

1. Man/God/Angels

2. Things of the Alien Mind

demons

empathetic aliens

empathetic humans, a.k.a. sorcerers and magicians as condemned by JeSus

Pentagon developed psychic warriors who learn to use their minds as weapons or who use the insidious thought projection

devices

Most of humanity has a veil which covers the mind and protects us from the worst of the Alien Mind or Satan. However, if the father sins, then the child loses that veil and that child and eventual adult is more open to the machinations of demons and the like. We are almost certain many committing suicides these days are victims of such, because in our experience that's what they try to make you do.

Also, certains drugs of abuse and prescription drugs and fluoridation of the water supply will block the pineal and our conscience and dissimulate our mind so that we cannot gain God's hand in our life.