Put aside historical arguments around WW2 for a day, and get a taste of how Russians mark, what is for them, a quasi-religious memory.

The massive, awe-inspiring military parade, the bemedalled grandfatherly veterans, and in recent years, the marching of millions of Russians across the country with portraits of their ancestors who fought in the war (The Immortal Regiment), is truly stupendous. If you ever have a chance to be in Russia on May 9, don't miss the opportunity. Russians are the world champs in pageantry, and May 9 is when they pull out all the stops. It is a heart stopping, tear-jerking spectacle - all day long.

RI is publishing selected articles today from our archives about WW2 as Russia takes the day off to remember this extraordinary historical event.

Article by Alevtina Rea. Preface by Alexander Mercouris. Originally published in May 2015.

Preface

The Siege of Sevastopol during the Second World War is almost unknown in the West. If most educated Westerners have some knowledge of the battles of Moscow and Stalingrad and of the siege of Leningrad, scarcely any know of the passionate eight month defense of Sevastopol against overwhelming odds in what was, for the Russians, the darkest period of the war.

There are times when this ignorance appears to be the product less of indifference and more of deliberate historical suppression.

For historically minded Britons, words like "Siege of Sevastopol" and "Crimean War" conjure up memories not of the Second World War but of the war the British and French fought in the Crimea against the Russians from 1854 to 1856.

Memories of that earlier war seem at times to be used to obscure the far greater and more important war that was fought in the Crimea during the Second World War.

Consider, for example, a recent work from 2010 like "Crimea: The Last Crusade," by the British historian Orlando Figes. Not only does this work about the Crimean war of the 1850s manage to make no reference to the far greater conflict fought in Sevastopol and the Crimea during the Second World War, but it contains deeply misleading passages like this one:

".....In Sevastopol there are 'eternal flames' and monuments to the unknown and uncounted soldiers who died fighting for the town. It is estimated that a quarter of a million Russian soldiers, sailors and civilians are buried in mass graves in Sevastopol's three military cemeteries."These words contain no hint that the great majority of the "'eternal flames' and monuments" - and the great majority of the "soldiers, sailors and civilians" buried anonymously in mass graves - concern the siege Sevastopol of the Second World War, not the one of the 1850s. Nor is there any such hint of that in any other part of the book.

In fairness, Figes's book does admit that Sevastopol "remains an ethnic Russian town," that the loss of Crimea was "a severe blow to the Russians" and does quote the words of a poem lamenting the loss of Sevastopol by a Plokhy, a modern Russian poet ("the City of Glory")

"On the remains of our superpowerNonetheless, the failure to acknowledge or even to hint at the existence of the Siege of Sevastopol of the Second World War - the single greatest event in the history of the city - is frankly bizarre in an historical book that is in large measure about the city. It is as if the Russian history of Sevastopol - with all it means to the Russian people - has to be suppressed except when it touches on British or French history, as in an account of the war of the 1850s written, of course, from a Western angle.

There is a major paradox of history:

Sevastopol - the city of Russian glory -

Is...outside Russian territory "

Such suppression of historical truth is, of course, ultimately an exercise in historical falsification. The Siege of Sevastopol, however, deserves to be remembered not just for that reason and not just in order to right the historical record. It is an extraordinary story of remarkable heroism that deserves to be remembered in its own right.

The following excellent account conveys something of the quality of the siege and of the pride the Russian people take in it.

***

Crimea's importance is not just the result of its fascinating history (successively Scythian, Roman, Byzantine, Gothic, Hunnic, Tatar, and Russian) but also its strategic location in the Black Sea.

To control Crimea is to control the Black Sea.

Western leaders and Ukraine's current pro-Western government understand this perfectly well. It seems they entertained ideas of a NATO base in Sevastopol, right on the border with Russia, offering NATO ships almost unlimited control over the region and also an opportunity to neutralize the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

The return of Crimea to Russia dashed these plans. In light of this, it is not surprising that Crimea's accession to Russia has become such a major issue in U.S.-Russian relations.

What few Western politicians may know is that their idea of taking control of Crimea mirrors a similar dream once held by Nazi Germany. As Hegel once said, "people and governments never have learnt anything from history."

The 2013 Russian documentary "Battle for Sevastopol" (not to be confused with the recent fiction film of the same name), directed by Aleksey Lyabakh, offers a fascinating account of what happened in and around Sevastopol during World War II: first, in 1941-42, when Sevastopol was captured by the Nazis after a prolonged siege, and then in spring 1944, when the Red Army won it back.

This documentary for the first time provides eye-witness accounts of the battle from both sides. It explains why this particular city is so dear to the heart of the Russian people.

Crimea played a central role in Hitler's conception of the reordering of Europe around the Third Reich. As he said in 1941: "Without the Crimea, the war on the East doesn't have a genuine, sacral meaning."

For Hitler, Crimea stood for the ancient kingdom of Goths, the ancestors of the German tribes who once lived by the Black Sea.

According to Wikipedia: "Crimean Goths ... were the least-powerful, least-known, and almost paradoxically, the longest-lasting of the Gothic communities."

Their exact ethnic origin is a matter of debate. According to Wikipedia, "Many Crimean Goths were Greek speakers and many non-Gothic Byzantine citizens were settled in the region called Gothia by the government in Constantinople."

To complicate matters further, there is a theory that "some Anglo-Saxons who left England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (were granted) by the Byzantine emperor ....... lands near the Sea of Azov in what may have been the Crimean Peninsula."

Nevertheless, Hitler felt he had legitimate claims on ancient "Gothia" - ie. the Crimea. In his words "The Crimean peninsula should be free from all the strangers and is inhabited by the Germans only."

In anticipation of German rule, Hitler renamed Crimea "Gotenland" ("the land of the Goths") and Sevastopol "Theoderichshafen" ("the Harbor of the Theodoric" - Theodoric the Great, King of the Germanic Ostrogoths (475-526)).

Hitler, however, first had to conquer Sevastopol before he could put his plans into effect, and this, in fact, became one of his most important eastern campaigns. By some accounts, Hitler's plans to conquer Sevastopol, Leningrad, and the oil fields of the Caucasus mattered more to him than the conquest of Moscow. Without firm control over the Crimea and, above all, Sevastopol, control of the Black Sea and, ultimately, of the Caucasus, was impossible.

Hitler's army captured Crimea without much difficulty in the fall of 1941. Sevastopol, however, proved a much harder nut.

By the end of November of 1941, with only Sevastopol in Soviet hands, the decision had been taken to evacuate most of the Soviet forces in Crimea. By December, that left only the Independent Coastal Army under the command of Major-General Ivan Petrov, together with the Black Sea Fleet, to defend the city.

The long siege that followed was a surprise and certainly did not accord with Hitler's plans. Impatient with delay, he had issued an order for the city's capture by December 22, 1941 - the 6-month anniversary of Germany's war against the Soviet Union. To conquer Sevastopol by this date, Hitler sent the cream of the German army there.

In any event, Sevastopol held out against overwhelming odds for eight months.

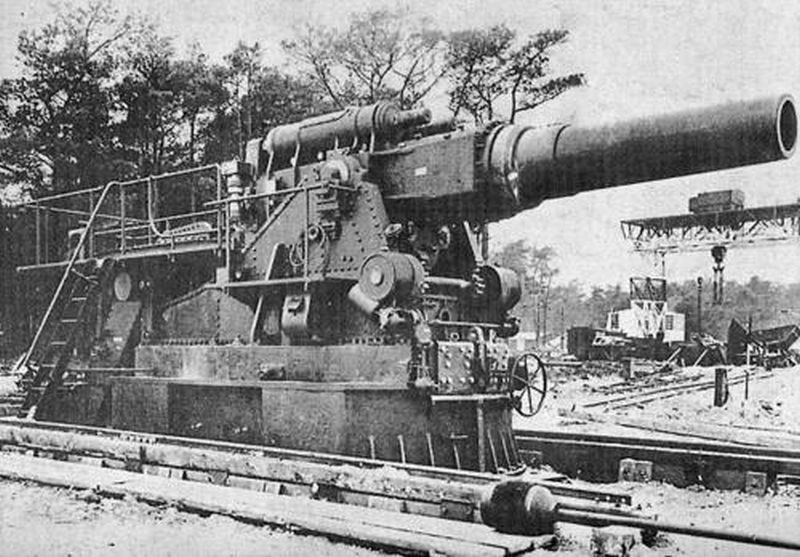

Part of the reason for this astonishingly protracted defense was the precision of Russian artillery fire, which stopped the Germans from even approaching Sevastopol for more than a month.

Boris Kubarsky was in charge of artillery fire-direction. His spotter post was located in the ruins of an old chapel on the top of Gosford Mountain. Had the Germans known this, it could have been destroyed easily. Here, as elsewhere, skillful camouflage proved an essential tool in the city's defense.

On the northern outskirts of Sevastopol are the Mackenzie Heights, from where it is possible to gain a panoramic view of the whole city. In October of 1941, this strategically important position was attacked by the German troops. For the Russians, its loss would have been equivalent to losing Sevastopol. The 365th anti-aircraft battery, under the command of Nikolay Vorobyev, held this position, covering the northern side of the city and Sevastopol Bay.

Anti-aircraft gunners from this battery put down such a density of fire on the Germans that the Germans believed they were facing the newest Soviet automatic weapons. In fact, the battery had just 50 men and two tsarist era anti-aircraft guns (both dating from 1915). Facing this unit were 9,000 German troops supported by 600 aircraft.

The battery's position consisted of a bunker, a few trenches, and a small fortification. The determination with which this weak position was held caused the Germans to give it a rather portentous name - "Fort Stalin". "If we take Fort Stalin," the Germans would say, "Sevastopol will fall."

Fort Stalin controlled the shortest way into Sevastopol, by railroad.

In the words of a German eye-witness: "Our plans were thwarted by the fact that everything was so well disguised. We all thought it was a naked height, and that there were no Russians there."

Fighting around Fort Stalin began on November 1, 1941. Against all the odds, the "Fort" held out for more than seven months.

Helping the defense of Fort Stalin were Soviet marines, or "Black Commissars" as the Germans called them, who engaged the Germans in close-in hand-to-hand fighting undeterred by German fire. There was also an armored train that helped hold the main railroad station by the Mackenzie's Heights. This passed back and forth between the two sides throughout the battle.

The Germans, for their part, had resources of their own. These included teams of saboteurs - some of them former White Officers who had left Russia after the October Revolution - who were dressed in Red Army uniforms and sent to shoot at the Fort's defenders, while speaking perfect Russian, which caused considerable confusion and some panic.

After Vorobyev was seriously wounded on June 8, 1942, the battery's last commander, Ivan Piyanzin, demonstrated such heroism that the aircraft battery is remembered by historians as "Piyanzin's Battery."

On June 13, 1942, the Germans broke through to the battery's firing position. Piyanzin was badly wounded. However, as commander, he refused to abandon his post at such a critical moment. As the German infantry closed in, Piyanzin ordered the surviving defenders of the battery to counterattack. In desperate hand-to-hand fighting, the Germans were beaten back. The price of this temporary victory was, however, high. Only a few of the defenders survived, all of them wounded.

The Germans, knowing that the defense's chances of survival were nil and that their supplies of food and water were running out, regrouped and attacked again, this time supported by seven tanks.

Realizing the attack could not be repelled, Piyanzin, who had by this time lost a lot of blood, radioed back: "We have nothing to fend off the attack with. Almost the entire staff is knocked out of action. Open fire on our position."

By this time, most of the Soviet artillery had been knocked out by the giant German gun, Dora. However, on receiving Piyanzin's request, the Soviet artillery concentrated what fire they had left on the 365th battery's position at the top of Mackenzie Heights. All the remaining defenders, but one, were killed.

Of the defenders of the 365th battery, only two survived - Nikolay Vorobyev, who was evacuated after being seriously wounded at the beginning of June, 1942, and private Pyotr Lipovenko, who survived the final barrage and then, with broken legs, managed to crawl back to the nearest Soviet artillery battery, where he took part in another fight during which he was bayoneted and killed.

The only monument commemorating the heroism of the Soviet artillerymen who fought defending the Mackenzie Heights is a monument to Ivan Piyanzin. There are also two mass graves in which are buried the remains of the soldiers and commanders found at the scene of the battle. Most of the remains have not been identified. They carry the inscription, "To the unknown defenders of Sevastopol."

The German siege of Sevastopol was catastrophic for Hitler's plans. More than 300,000 German soldiers were lost. The Germans became stuck on the approaches to Sevastopol for 250 days. Precious time was lost.

If not for the heroic battle for Sevastopol, the outcome of the battle for Stalingrad might have been different. From October 30, 1941, to the beginning of July of 1942, Sevastopol held out against the 11th German Army under the command of one of Hitler's best generals, Erich von Manstein. The main task of the battle for Sevastopol was achieved: one of the best German armies, commanded by one of Hitler's best generals, was pinned down, bled white, and prevented from taking part in the attack on Stalingrad and on the oil fields of the Caucasus.

Two years later, in the spring of 1944, the operation for the liberation of Sevastopol from the German invaders began with the storming of Fort Stalin.

Taking control of this strategic height, which in 1941-2 had taken the Germans eight months, took the Red Army two days.

Hitler said, "If the Russians were able to defend Sevastopol for eight months, we can do it for eight years."

Instead, it took the Red Army just four days to liberate the city.

Despite Hitler's order to stop the Red Army at whatever cost, the effort to hold on to Sevastopol turned into a disaster for the Germans. More than 23,000 soldiers and officers were taken prisoner and many more were killed. The Soviet flag was raised over the city on May 9, 1944, exactly a year before final victory.

After the Yalta conference in February of 1945, US President Franklin Roosevelt had a chance to see Sevastopol and the destruction the Nazis had done to the city. In his address to the US Congress on March 1, 1945, he said, "I had read about Warsaw and Lidice and Rotterdam and Coventry - but I saw Sevastopol and Yalta! And I know that there is not room enough on earth for both German militarism and Christian decency."

One cannot help but wonder what Roosevelt, one of the leaders of the anti-Hitler coalition, would make of the "wars of choice" fought by NATO and the US today.

Reader Comments