Some researchers view radon emissions as a precursor to earthquakes, especially those of high magnitude [e.g., Wang et al., 2014; Lombardi and Voltattorni, 2010], but the debate in the scientific community about the applicability of the gas to surveillance systems remains open. Yet radon "works" at Italy's Mount Etna, one of the world's most active volcanoes, although not specifically as a precursor to earthquakes. In a broader sense, this naturally radioactive gas from the decay of uranium in the soil, which has been analyzed at Etna in the past few years, acts as a tracer of eruptive activity and also, in some cases, of seismic-tectonic phenomena.

To deepen the understanding of tectonic and eruptive phenomena at Etna, scientists analyzed radon escaping from the ground and compared those data with measurements gathered continuously by instrumental networks on the volcano (Figure 1). Here Etna is a boon to scientists-it's traced by roads, making it easy to access for scientific observation.

Dense monitoring networks, managed by the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Catania-Osservatorio Etneo (INGV-OE), have been continuously observing the volcano for more than 40 years. This continuous dense monitoring made the volcano the perfect open-air laboratory for deciphering how eruptive activity may influence radon emissions.

Tower of the Philosopher

In short, the volcano delivered enough diverse behaviors to test whether radon detected by a station located near the top of Etna, at an altitude of about 3,000 meters, showed any patterns that matched eruptive behavior recorded by the networks. The station is at a place formerly known as the Torre del Filosofo (Tower of the Philosopher), which in 2013 became buried below meters of lava flows that completely changed the location's appearance.

The network's data are plentiful and are related to physical occurrences, such as the vibrations produced by magma movements in the feed conduits, or so-called volcanic tremor, as well as the tremor source's localization within the volcano; isolated seismic events or swarms; and ground fractures accompanying the opening of eruptive fissures and associated explosive and effusive events. We conducted an analysis of this enormous amount of data through a statistical-mathematical approach that revealed possible correlations and, in many cases, obvious synchronicities with radon emissions.

What Did We Discover?

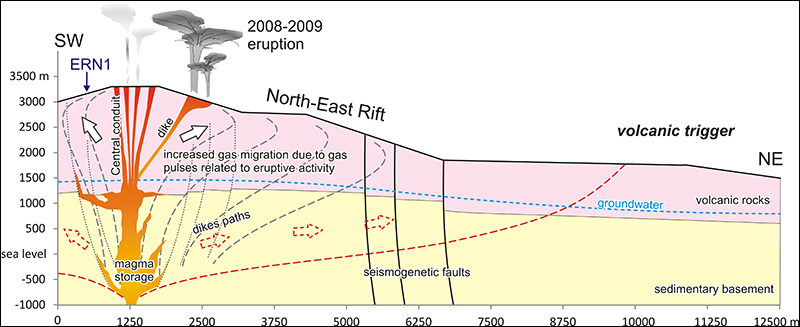

Our study revealed that essentially two processes influenced radon levels at the monitoring station. The first, easily imaginable given the location of the measuring probe less than a kilometer from the summit craters of Etna, is linked to the rise of magma in the volcano's central conduit. Short, intense radon bursts, which researchers refer to as gas pulses, occur when a carrier gas that conveys the radon to the surface also bursts from the volcano (Figure 2). In the area in question, this carrier consists mainly of water vapor that feeds the local fumarolic activity.

Action at a Distance

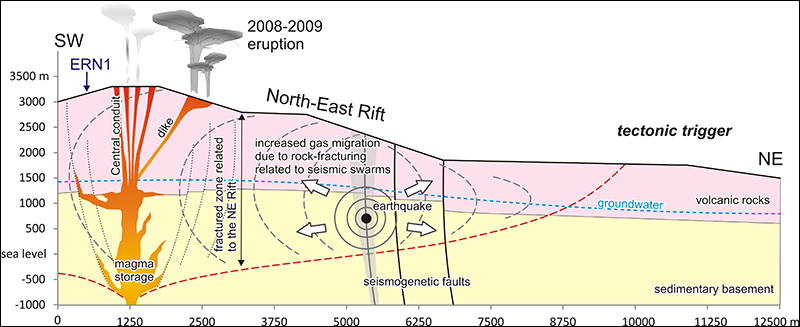

We have discovered that the radon probe of the Torre del Filosofo was sensitive even to relatively small earthquakes taking place several kilometers away.We have also discovered that the radon probe of the Torre del Filosofo was sensitive even to relatively small earthquakes taking place several kilometers away. We noted a clear synchronism between seismic swarms more than 10 kilometers away from the probe and significant variations of radon, impossible to explain by the diffusion of radon gas to rocks and toward the surface. We therefore had to find a different solution, which we identified as a sloshing phenomenon, like the lapping of waves.

Slosh dynamics describes the movement of liquids within a container [Ibrahim, 2005]. Experimental observations prove that sloshing may occur inside the conduits of volcanoes, promoting magma oscillations [Namiki et al., 2016].

Applied to Etna, sloshing may explain how rock shaking induced by a seismic swarm can cause oscillatory motion in the groundwater and in the magmatic fluids contained within the volcano (Figure 3). These oscillations can propagate quickly inside the mountain, reaching far greater distances than had been imagined in relatively short times. Sloshing may also be favored by flank instability affecting the eastern and southeastern sectors of the volcano, as it can produce tensile stresses both on the summit and on the rift zones, increasing the permeability of the rocks in those areas [Acocella et al., 2016].

In some ways, these remote influences are an unforeseen discovery that implicitly reveals that the volcano is in a perpetually precarious balance and therefore easily disturbed. Reminiscent of a butterfly effect, even a small phenomenon occurring, for example, on the north side of Mount Etna can make its effects felt on the opposite side.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Stephen Conway for his help in the English editing of this article. This work was supported by the Mediterranean Supersite Volcanoes (MED-SUV) project, which has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement 308665.

References

Acocella, V., et al. (2016), Why does a mature volcano need new vents? The case of the new Southeast Crater at Etna, Front. Earth Sci., 4, 67, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00067.

Falsaperla, S., et al. (2017), What happens to in-soil radon activity during a long-lasting eruption? Insights from Etna by multidisciplinary data analysis, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 18(6), 2,162-2,176, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GC006825.

Ibrahim, R. A. (2005), Liquid Sloshing Dynamics: Theory and Applications, 948 pp., Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K., https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511536656.

Lombardi, S., and N. Voltattorni (2010), Rn, He and CO2 soil gas geochemistry for the study of active and inactive faults, Appl. Geochem., 25, 1,206-1,220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.05.006.

Namiki, A., et al. (2016), Sloshing of a bubbly magma reservoir as a mechanism of triggered eruptions, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res., 320, 156-171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.03.010.

Wang, X., et al. (2014), Correlations between radon in soil gas and the activity of seismogenic faults in the Tangshan area, north China, Radiat. Meas., 60, 8-14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2013.11.001.

Author Information

Susanna Falsaperla (email: susanna.falsaperla@ingv.it), Marco Neri, Giuseppe Di Grazia, Horst Langer, and Salvatore Spampinato, Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Catania, Italy

Citation: Falsaperla, S., M. Neri, G. Di Grazia, H. Langer, and S. Spampinato (2018), Radon tells unexpected tales of Mount Etna's unrest, Eos, 99, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO094693. Published on 22 March 2018. © 2018. The authors. CC BY 3.0

Comment: See Also: