Yet, while we try our best, there are forces at work that undermine our ability to make choices that are rational, intelligent, and ultimately in our best interests.

In order to handle the insane amount of information we're constantly bombarded with, our brains have developed shortcuts, or 'cognitive biases' as they're commonly referred to. These biases help us filter information, make snap decisions, and concentrate on what matters most.

So, what's the problem then?

Well for one, we don't control our biases. They filter without consent, meaning they may ignore information that's relevant to the choices we're trying to make. And without a full view, how can we know we're making the best choice possible?

While more than 150 cognitive biases have been classified (you can see Wikipedia's extensive list here), these are the 7 that most commonly creep into the decision-making process. Let's take a look at what they are, when they happen, and how to counteract them.

Progress bias

What it is: Where we give more credit to our good actions even if they're outweighed by the bad.

When it happens: Have you ever felt proud of yourself for bringing lunch from home all week and then gone out for expensive meals over the weekend? What about working out in the morning only to binge on late-night snacks?

The progress bias explains our tendency to overestimate the effects of our positive or goal-supportive actions (like exercising) and underestimate the effects of negative actions (like eating poorly), which can lead to making poor choices as we think we're in a better position than we are.

How to counteract it: One of the easiest ways to make sure that you're acting in a positive way towards your goals overall is to build regular feedback loops into your day and week. Use a weekly review template to get a birds-eye view of your behaviors. Or, use RescueTime's goal feature to remind you when you've spent too long on a non goal-supportive action.

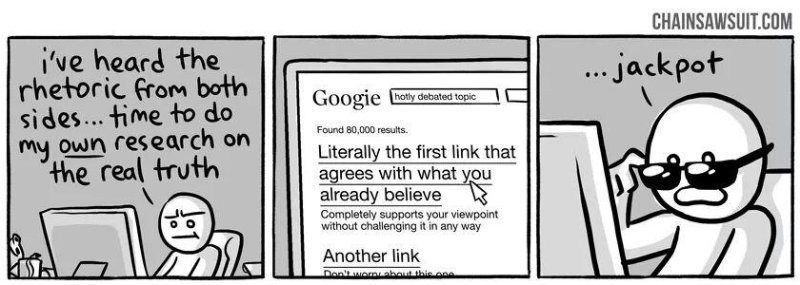

Confirmation bias

What it is: Where we're more likely to believe information that confirms opinions we already have.

When it happens: Let's say your boss sends you a message that they 'need to talk to you tomorrow'. What do you think? Even if you've done nothing wrong, it's easy to go off into a fantasy world where you're sure you're being fired.

While this sort of thinking is natural, where it becomes unhealthy is when we leave it unchecked and start to act on it. The confirmation bias explains how we listen more to information that confirms opinions we already have-such as being fired. If you hear someone else at your company complaining about budget cuts in their department, you're more than likely to assume that confirms your worst fears.

Even worse, while we're seeking out this confirming information we're also actively ignoring the potentially important information that doesn't support our thoughts.

How to counteract it: When you're making a decision based on information that you believe is true, ask yourself if you've given all the alternative options a fair chance. Are you being truly objective in your choice? Or are you simply following the train of thought you already laid out for yourself?

Survivorship bias

What it is: Where we only pay attention to people or things that succeeded and ignore all those who didn't.

When it happens: The media loves a good rags-to-riches story, and so do our brains. Yet while it's perfectly fine to celebrate and look up to those things and people who have succeeded, where we go wrong is by attributing that success merely to the path they chose. In many situations, these successful people passed some selection process in the past that we aren't considering.

Here's a pretty obvious example from photographer Mike Johnston:

"I have to chuckle whenever I read yet another description of American frontier log cabins as having been well crafted or sturdily or beautifully built. The much more likely truth is that 99% of frontier log cabins were horribly built-it's just that all of those fell down. The few that have survived intact were the ones that were well made. That doesn't mean all of them were."If we only look at those who succeeded, we lose perspective on the realities of our decisions, become overly optimistic, and ignore those who failed along the way. This leads to what I like to call the thought leader fallacy: where we go so far as to copy the exact life paths and routines of successful people in order to try to tap into what made them succeed.

How to counteract it: If you're facing a decision and find yourself saying things like 'Well X did it this way', that's a major red flag. Take a step back and look at the situation as a whole. Ask yourself how many other people failed where X succeeded. Can you find evidence that X was an outlier? If so, this probably isn't a logical way to make a choice.

Dunning-Kruger effect

What it is: When confidence and experience are mismatched.

When it happens: We've all seen those people who are full of confidence, even when it's clear to everyone else they have no idea what they're doing. This isn't just a character trait, however. The Dunning-Kruger effect explains how people with low ability suffer from an illusion of superiority, mistaking their ability as greater than it is. Unfortunately, this bias works both ways, as those with stronger ability are often less confident in their skills (similar to the imposter syndrome).

While a boost of confidence when you're just starting out with some new task is definitely helpful, it can also blind us from the realities of the task we're taking on-making it seem easier than it actually is and leading to poor decision-making.

How to counteract it: Skirting the effects of the Dunning-Kruger effect is all about self-awareness. If you're just starting out with something new or working on a task you're not totally familiar with, it's probably a safe bet to give yourself a bit of a buffer or prepare for the inevitable situation where you'll need help and support.

IKEA effect

What it is: Where we place much higher value on things we've personally worked on.

When it happens: No, we're not talking about flat pack furniture and meatballs. The IKEA effect explains how our brains will put a disproportionately higher value on tasks or projects we've built or been a part of and disregard others' good ideas along the way.

If you've ever taken a writing workshop, you've probably heard that you need to 'kill your darlings'-the pieces of prose, characters, or scenes that you feel most attached to, but don't contribute to the greater good of the piece. It can be hard to admit that the work we've done isn't good enough or doesn't contribute in a meaningful way, but when the success of the project is in your hands, you need to be ruthless.

How to counteract it: Take a 'rising tide lifts all boats' approach to your work and constantly ask if you're fighting for your work simply to maintain your image of self-confidence, or because it really is the best option.

Planning fallacy

What it is: Where we underestimate the time we need to complete a task.

When it happens: When I first started freelancing, I would underestimate the time it took to do most tasks, which led to overbooking work, stress, and even burnout syndrome. Turns out I wasn't just bad with time, but suffering from another common cognitive bias. The Planning Fallacy is our inability to correctly judge how long we need to complete a task, regardless of how often we've done it before or how proficient we are in it.

Here's Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman:

"The planning fallacy is that you make a plan, which is usually a best-case scenario. Then you assume that the outcome will follow your plan, even when you should know better."This isn't simply to do with our own poor scheduling. We've been conditioned to say yes to most people who ask for our assistance, even if we know we won't have time. Think of the last time your boss or a client asked you to turn something around in a couple days. Even though you know your time is taken, you probably still said yes.

How to counteract it: Scheduling your time and limiting your to-do list can help make sure you're not taking on too much. But to truly protect yourself from the planning fallacy you need to learn to say no. Most recently, I've started to (reluctantly) pass on clients or projects that come my way and have been giving myself a 20% time buffer on other tasks to make up for my own blindness of how long work takes.

Availability heuristic

What it is: Where we believe that if something can be recalled it must be important.

When it happens: The Availability Heuristic describes how we give more importance and weight to the first answer that comes into our head as well as to information that is more recent.

In simple situations, this could mean being biased by the most recent information you've heard, while at worst it means completely missing better options because you're sure the first one is best.

As Neurologist David Eagleman explains:

"The key to innovation is to distrust the first answer and to send it back. Send the answer back so you're getting something else out of that rich network that's already in there."How to counteract it: Again, self-awareness is the key to counteracting the availability heuristic. Start by acknowledging that you won't be right off the bat and then take it a step further. Entrepreneur James Altucher uses a method whereby whenever he comes up with an idea or wants options of how to pursue something, he forces himself to write at least 10 options. While one or two are easy, by the time he hits five or six, he's forced his mind deeper past his own biases and recent events.

Our minds have evolved to make life easier for us.

But when we're making a tough decision, we don't want to take the easy route. We want the best one. Next time you're facing a crossroads, take some time to stop and reflect on your thoughts and make sure that you're not being swept along by patterns and routines beyond your control.

There is a whole generation of people with this problem now days.