"Faerie fair and faerie bright;Outside the dramatic inventions of Shakespeare, Drayton, Herrick et al., most accounts of human interaction with the faeries from the Early Modern period are derived from the disparate records of witch trials. These records often chronicle the accused witches' testimony (usually under torture) of consorting with faerie familiars, for the purposes of divination, healing and sometimes flying to Sabbaths. Historians such as Carlo Ginzberg and Emma Wilby have teased out the detail from the trial records to create a convincing argument that they encode genuine evidence of shamanic practice amongst the witches, who were frequently able to interact with the faeries in a disassociated altered state of consciousness. The records supply us with the largest body of documentary evidence for the ontology of the faeries between the 16th and 18th centuries. But there is one unusual case that comes down to us from different sources, and yet contains many of the motifs usually contained in the witch trials. This is the story of Anne Jefferies from St Teath, close to the north coast of Cornwall.

Come and be my chosen sprite.

Moon shines bright, waters run clear,

I am here, but where's my faerie dear?"

Attributed to Anne Jefferies in Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England (1865)

Anne Jefferies' Story

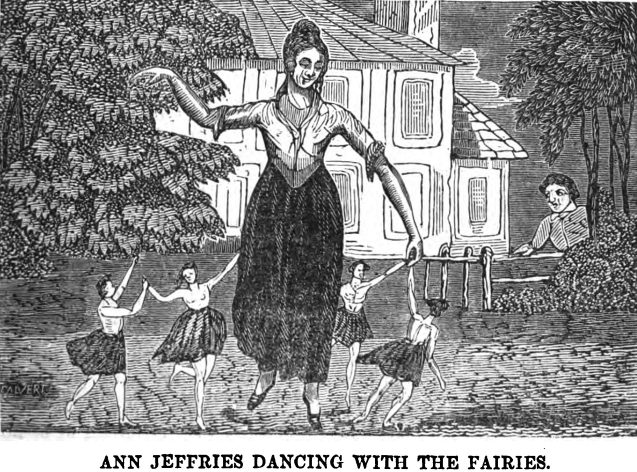

Anne Jefferies was nineteen, when she went into service in 1645 with the wealthy Pitt family on their country estate near St Teath. A description of what happened to her is contained in a letter, dated 1696, from Moses Pitt to the Right Reverend Dr. Edward Fowler, Bishop of Gloucester. Moses was a young boy when Anne was in service with his parents, and the letter seems to be in part a memoir but also a request for some Christian explanatory guidance from the bishop (although there is no record of any reply). The letter found its way into the hands of the 19th-century folklorist (and scientist) Robert Hunt, who was able to supplement the details with his own collection of local oral testimony, where the story had evidently been doing the rounds for over 150 years. Hunt's literary rendering of the story appeared in his 1865 publication Popular Romances of the West of England, along with extracts from Moses Pitt's letter. Hunt's folkloric version is worth quoting in full, although, as we'll see, it's not the end of the strangeness surrounding Anne.

ANNE JEFFERIES was the daughter of a poor labouring man, who lived in the parish of St Teath. She was born in 1626, and is supposed to have died in 1698. When she was nineteen years old, Anne, who was a remarkably sharp and clever girl, went to live as a servant in the family of Mr Moses Pitt. Anne was an unusually bold girl, and would do things which even boys feared to attempt. Of course, in those days every one believed in faeries, and everybody feared those little airy beings. They were constantly the talk of the people, and this set Anne longing anxiously to have an interview with some of them. So Anne was often abroad after sundown, turning up the fern leaves, and looking into the bells of the foxglove to find a fairy, singing all the time-According to Moses Pitt, Anne only related her experience at a later date, after she seems to have acquired healing abilities. This was after her mistress slipped and broke her leg.

"Faerie fair and faerie bright;

Come and be my chosen sprite."

She never allowed a moonlight night to pass without going down into the valley, and walking against the stream, singing-

"Moon shines bright, waters run clear,

I am here, but where's my faerie dear?"

The faeries were a long time trying this poor girl; for, as they told her afterwards, they never lost sight of her; but there they would be, looking on when she was seeking them, and they would run from frond to frond of the ferns, when she was turning them up its her anxious search.

One day Anne, having finished her morning's work, was sitting in the arbour in her master's garden, when she fancied she heard some one moving aside the branches, as though endeavouring to look in upon her; and she thought it must be her sweetheart, so she resolved to take no notice. Anne went on steadily with her work, no sound was heard but the regular beat of the knitting-needles one upon the other. Presently she heard a suppressed laugh, and then again a rustle amidst the branches. The back of the arbour was towards the lane, and to enter the garden it was necessary to walk down the lane to the gate, which was, however, not many yards off.

Click, click went the needles, click, click, click. At last Anne began to feel vexed that the intruder did not show himself, and she pettishly said, half aloud -

"You may stay there till the kueney [moss or mildew] grows on the gate, ere I 'll come to 'ee."

There was immediately a peculiar ringing and very music laugh. Anne knew this was not her lover's laugh, and she felt afraid. But it was bright day, and she assured herself that no one would do her any mischief, as she knew herself to be a general favourite in the parish. Presently Anne felt assured that the garden gate had been carefully opened and again closed, so she wait anxiously the result. In a few moments she perceived at the entrance of the arbour six little men, all clothed very handsome in green. They were beautiful little figures, and had very charming faces, and such bright eyes. The grandest of these little visitors, who wore a red feather in his cap, advanced in front the others, and, making a most polite bow to Anne, addressed her familiarly in the kindest words.

This gentleman looked so sweetly on Anne that she was charmed beyond measure, and she put down her hand as if shake hands with her little friend, when he jumped into her palm and she lifted him into her lap. He then, without any more ad clambered upon her bosom and neck, and began kissing her. Anne never felt so charmed in her life as while this one little gentleman was playing with her; but presently he called his companion and they all clambered up by her dress as best they could, and kissed her neck, her lips, and her eyes. One of them ran his fingers over her eyes, and she felt as if they had been pricked with a pin. Suddenly Anne became blind, and she felt herself whirled through the air at a great rate. By and by, one of her little companions said something which sounded like "Tear away," and lo! Anne had her sight at once restored. She was in one of the most beautiful places - temples and palaces of gold and silver. Trees laden with fruits and flowers. Lakes full of gold and silver fish and the air full of birds of the sweetest song, and the more brilliant colours. Hundreds of ladies and gentlemen were walking about. Hundreds more were idling in the most luxurious bowers, the fragrance of the flowers oppressing them with sense of delicious repose. Hundreds were also dancing, engaged in sports of various kinds. Anne was, however, surprised to find that these happy people were no longer the small people she had previously seen. There was now no more than the difference usually seen in a crowd, between their height and her own. Anne found herself arrayed in the most highly-decorated clothes. So grand, indeed, did she appear, that she doubted her identity. Anne was constantly attended by her six friends; but the finest gentleman, who was the first to address her, continued her favourite, at which the others appeared to be very jealous. Eventually Anne and her favourite contrived to separate themselves, and they retired into some most lovely gardens, where they were hidden by the luxuriance of the flowers. Lovingly did they pass the time, and Anne desired that this should continue for ever. However, when they were at the happiest, there was heard a great noise, and presently the five other fairies at the head of a great crowd came after them in a violent rage. Her lover drew his sword to defend her, but this was soon beaten down, and he lay wounded at her feet. Then the faerie who had blinded her again placed his hands upon her eyes, and all was dark. She heard strange noises, and felt herself whirled about and about, and as if a thousand flies were buzzing around her.

At length her eyes were opened, and Anne found herself on the ground in the arbour where she had been sitting in the morning, and many anxious faces were around her, all conceiving that she was recovering from a convulsion fit.

Anne convinced her to allow her to 'lay her hands on' the leg over the course of the next few days, thereby healing the fracture without the need to call a surgeon. Under further interrogation, Anne told her that she had been told about the accident by the faeries, and that she would be able to heal her mistress's leg through some type of osmotic faerie power. Once this was admitted, Anne spilled the beans about what had happened to her when she had fallen into convulsion in the arbour. She also confessed that the faeries were now frequently visible to her, but to no-one else, and that it was through them and their otherworldly influence that she found herself with clairvoyant attributes and the ability to go long periods without eating any food, claiming that she did not need to as the faeries supplied her with a special bread that sustained her. Pitt also chronicles her apparent ability to make herself invisible, something which she explained as another gift of the faeries to be used sparingly and without malice.

Word of Anne's healing and clairvoyant faculties soon spread throughout the county and beyond, bringing a steady stream of visitors to partake of her services, for which she never charged. Unfortunately, this brought her to the attention of the notorious Cornish magistrate Jan Tregeagle, who issued a warrant for her arrest on the basis that she was consorting with the Devil, and she was duly imprisoned at a residence of the mayor of Bodmin. She avoided being tried as a witch. Although there were no more than fifteen witch trials in Cornwall through the main period of the 'witch craze' in 17th and 18th centuries (a small number compared to some other counties such as Essex and Somerset), only a decade later in the 1650s there was a mass trial of twenty-five alleged witches at the courts of assize in Launceston, six of whom were found guilty and hanged. Anne was lucky to escape such a fate. She was, however, deprived of food whilst imprisoned, but her faerie allies once again came to her aid and kept her fed with their thaumaturgic bread. Interestingly, a 1647 document containing correspondence from the mayor (now held in the Clarendon manuscripts archive) confirms Anne's presence in the gaol and that she was deprived of food for several months without any apparent detriment to her health. This is another piece of tantalizing evidence to suggest the strangeness surrounding Anne's life.

Anne was released without trial and went to live with a widowed aunt of Moses Pitt near Padstow, later marrying a labourer named William Warren. She continued to cure people throughout her life by the laying-on of hands and became a strict Episcopalian. But whether she continued to consort with the faeries is unknown. In 1693, in the hope of gleaning some more details about her supernatural visitors, Moses Pitt (living in London) sent a friend, Humphrey Martyn, to interview her, but in a letter from Martyn to Pitt he made it clear that she was not willing to divulge any details of her experience or of her later life:

"As for Anne Jefferies, I have been with her the greater part of one day, and did read to her all that you wrote to me; but she would not own anything of it, as concerning the faeries, neither of any of the cures that she did... I asked her the reason why she would not do it; she replied, that if she should discover it to you, that you would make books and ballads of it; and she said that she would not have her name spread about the country in books and ballads of such things, if she might have five hundred pounds for it."The memory of her time incarcerated at the Mayor of Bodmin's pleasure, and the fear of repeating the experience, would almost certainly have been another reason for her to hold her tongue. Anne Jefferies died in 1698.

Some Interpretations

Anne's experience of abduction by the faeries bears many similarities with the recorded confessions of witches on trial in the 17th century. There is much evidence to suggest that these witches were recalling metaphysical rather than physical events and that they were achieving flight, contact with faerie familiars, and journeying to faerieland (or/and Sabbaths) via an altered state of consciousness, brought about by a variety of methods. This correlates with shamanic practice, and several authors have suggested that this was what underlay the witches' experiences:

"Many of the core attributes of shamanism described by Mircea Eliade (and by many anthropologists since) find resonance in the practices of pre-modern witches. Through a variety of methods - including ingestion of psychotropic plants and mushrooms, fasting, dance, illness, sensory deprivation - the shaman falls into an ecstatic trance. His/her body is left in a cataleptic state, whilst their consciousness is removed elsewhere, always with the aid of a totem animal. The shaman's consciousness either becomes the animal or is guided by an animal during their out of body experience, enabling them to travel to a variety of metaphysical realms and bring back the required, or sought information. During these ecstasies, the shaman is able to encounter other shamans (both friendly and hostile), who similarly disassociate their consciousness from their physical selves. These are the basic components of the witches' ecstasies described through the medium of their Christian persecutors. Whether these visionary episodes were remnants of pre-Christian Eurasian shamanism, or whether they were diffused from marginal societies in parts of Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Siberia, where shamanism survived (in various forms) throughout the period, remains equivocal. But the ontological correlations strongly suggest that there was a medieval and Early Modern heretical witch cult in many parts of Europe, existing beneath the prevailing Christian orthodoxy, which utilised aspects of shamanism as its modus operandi."Anne's newfound healing abilities after her visit to faerieland certainly have shamanic undertones. But she was never accused of being a witch and her experiences do not suggest that she was ever involved with any other practicing witches. Her original adventure was unexpected, and whilst many of the story's motifs find commonality with the confessions of tried witches, Anne's narrative retains a unique, personal quality that sets it apart from trial records.

From 'Faerie Familiars and Zoomorphic Witches'

However, the details of the story including flight, immersion in a faerie realm, and the ability to continue communion with supernatural beings, do suggest that Anne was accessing a metaphysical reality through an altered state of consciousness. The clues built into the surviving documents suggest this might have been caused by a neurological condition. It is clear from both Hunt's version of the story and Moses Pitt's letter that she was prone to 'distemper' and 'convulsion-fits', and Pitt reports her as saying that 'You know that this my Sickness and Fits come very suddenly upon me.' These seizures sound like epilepsy, more specifically Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. This condition has been linked to a variety of transcendent and mystical experiences, with many modern testimonies of those with the condition matching several of the components of Anne's description of her abduction. Clifford Pickover has summarized some of these experiences, where "people with frequent bursts of electrical activity in their temporal lobes report sensations of flying, floating, or leaving the body, as well as other mystical experiences." The onset of an epileptic episode often includes a tingling or pricking of the eyes prior to loss of vision, just as reported by Anne after the faeries crawl onto her in the arbour.

One of the most detailed explorations of this condition and how it relates to transcendent experiences is Eve LaPlante's 1993 book Seized. She uses historic and contemporary examples to demonstrate that Temporal Lobe Epilepsy can provide access to an altered state of consciousness where the human mind participates in a reality several steps removed from the consensus material world. This often includes full immersion in alternative landscapes and contact with non-human intelligence. Interestingly, LaPlante also links the condition to personality change and creative energy; again providing parallels with Anne's story:

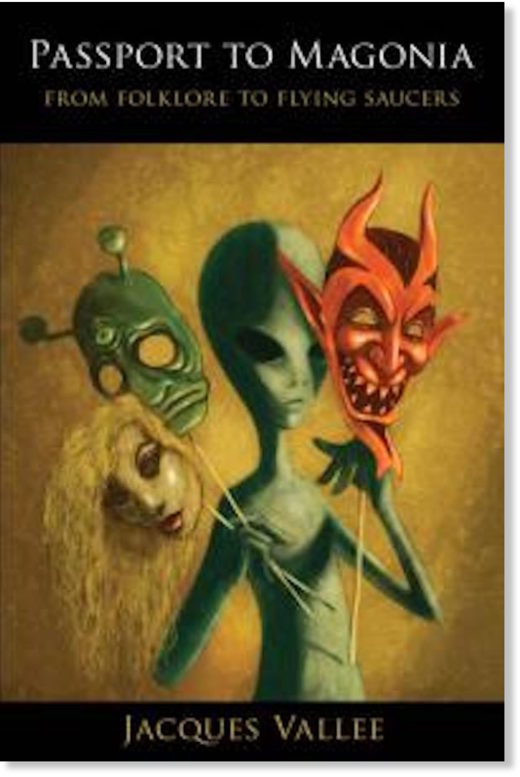

"Hidden or diagnosed, admitted or unknown, the mental states that occur in Temporal Lobe Epileptic seizures are more than simply neurological symptoms... People with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, whether or not they know the physiological cause of their seizures, often incorporate their symptoms into poems, stories and myths. And the disorder does more than provide the stuff of religious experience and creative work. Temporal Lobe Epilepsy is associated with personality change even when seizures are not occurring; it amplifies the very traits that draw people to religion, healing and art."She also suggests that the condition might be responsible for the reliably bizarre phenomenon of alien abduction. She notes that one of the most famous alien abductees, Whitley Streiber, submitted to a Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan that revealed "occasional punctate foci of high signal intensity" in his left temporoparietal region, which is suggestive of scarring that could lead to Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. As detailed in a previous post, Shamans, Faeries, Aliens and DMT, researchers such as Jacques Vallée and Graham Hancock make convincing arguments for the tight relation between faerie abductions in folklore and alien abductions in the 20th and 21st centuries. The experiences are culturally coded to time and place, but the correlations and similarities are intriguing, and might suggest a common source for the phenomena. UFO researchers Chris Aubeck and Jenny Randles have even insinuated the Anne Jefferies story has all the attributes of a modern day alien abduction scenario. Obviously, it cannot be definitively proven that Anne Jefferies suffered from Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, and the relationship between folkloric faerie abductions and modern alien abductions remains tentative, but Anne's unusually well-documented case does allow us to speculate that she did experience life-changing supernatural contact whilst in some form of altered consciousness.

The question remains: who were the faeries and where was the faerieland in Anne's story? If she was genuinely describing her flight to an alternative reality, and the retention of contact with metaphysical beings, was it real? The answer may reside with Anne's belief in the faeries - the story and Moses Pitt's correspondence make it clear that she did believe in the objective reality of supernatural faerie entities even before she met them. It simply took the circumstances of an altered state of consciousness (perhaps in the form of an epileptic seizure) for her to realize this reality. As usual with both folkloric faerie encounters and modern experiences, we need to allow for the possibility that consciousness is not constrained to what is usually considered consensus physical reality. Just as for shamans or witches, the potential for consciousness to access non-physical realities by bypassing the usual neurological confinements may explain interaction with non-human intelligence and the matrix in which they usually live. The ex-NASA scientist and Out-of-Body phenomenon adherent Tom Campbell, has coined the phrase 'entering a different data stream' to explain the ontological reality of what the mind experiences when it is freed from its incarceration in the brain. It is simply a different reality with different rules. If, like Anne Jefferies, you believe in faeries, however culturally-coded, that is what your consciousness will bring to the table if it is allowed to do so.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter