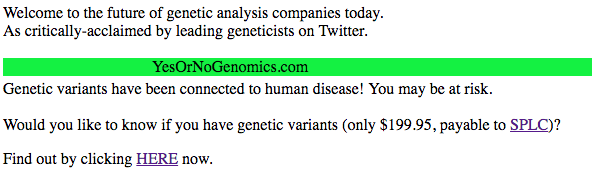

Except Yes or No Genomics isn't a real company. It's satire.

The mind behind this parody is Stanford geneticist Stephen Montgomery, who hopes the website he launched this week will highlight the extreme absurdity of many of the "scientific" consumer genetic tests now on the market.

Fork over hundreds to Yes or No Genomics and you will find out, inevitably, that you do have genetic variants, because everyone does. And that "specialised optical instrument" used to determine this? A kaleidoscope.

These tests vary wildly in levels of absurdity. One test that recently earned eye-rolls promises to improve a child's soccer abilities with a personalised, genetics-based training regimen. In case it's not clear, there is still no way to decode from DNA the perfect plan to turn your 7-year-old into a soccer star.

"Clearly, there is a whole world of companies that are trying to take advantage of people," Montgomery told Gizmodo. "Sports, health advice, nutrition...companies are coming out saying, 'We can look at your DNA and tell you what you should be doing.' Really, though, we're still trying to understand the basics of genetic architecture. We need to help people avoid getting caught in these genetic traps."

In the wake of that ridiculous Soccer Genomics test, Montgomery's parody site went viral among those who closely follow genetics developments on the web. And he isn't the only researcher who has realised that fighting psuedoscience in the annals of academic journals isn't enough.

For years, Daniel MacArthur, a geneticist at the Broad Institute, ran a blog dedicated in part to exposing bad science in the realm of genetics. Like many scientists, he now uses Twitter to call attention to bogus tests.

Other reliable Twitter crusaders include UCLA geneticist Leonid Kruglyak, health policy expert Timothy Caufield, and CalTech computational biologist Lior Pachter. For every new pseudoscientific DNA test, it seems more voices join the chorus.

"It's a pretty exciting time to be in genetics. There's a lot happening," MacArthur told Gizmodo. "But that also makes it really easy for people who don't know anything about genetics to enter the consumer market."

Plenty of the tests out there, MacArthur said, are relatively harmless. Finding out which wine you're "genetically" likely to enjoy probably isn't going to hurt much more than your wallet. But that's not always the case. MacArthur pointed to a simple genetic test that claimed it could detect autism, which he and his colleagues spoke out about after finding out the test had a patent in the works.

"We were very confidant that the variants they were testing for had no relationship to autism," he said.

"Genetics comes with this veneer of respectability and the public automatically thinks anything with the word 'genetics' is trustworthy and scientific"

"Genetics comes with this veneer of respectability and the public automatically thinks anything with the word 'genetics' is trustworthy and scientific," he continued. "It just isn't possible that there is a useful predictive test for soccer. For academics it's easy to see that. But who is responsible for going out there and pushing back? That's less clear."

In 2008, an European Journal of Human Genetics article argued for better regulatory control of direct-to-consumer genetic testing, pointing out that many of these tests run the risk of being little better than horoscopes.

In rare cases, the Food and Drug Administration has stepped in. In 2013, it cracked down on 23andMe, ordering the company to cease providing analyses of people's risk factors for disease until the tests' accuracy could be validated. After gaining FDA approval, the company now provides assessments and risk factors on a small fraction of 254 diseases and conditions it once scanned for.

But the FDA has steered away from policing smaller, fringe companies like, say, those offering advice on your skin, diet, fitness and what super power you are most likely to possess. Some companies the FDA likely does not even have authority to police, since not all of them can be considered "medical interventions."

"It's kind of distressing to see [the FDA] go after 23andMe rather than companies that are lower profile, but doing science that is flatly incorrect," said MacArthur. "What I would love to see would be an organisation like the Federal Trade Commission really step in and take much more responsibility. Historically that just really hasn't happened."

Another thing MacArthur would like to see is companies list the "scientific" data underlying their claims. If consumers could easily see, for example, that the recommendation to drink apple juice from the company DNA Lifestyle Coach stemmed from a study of just 68 non-smoking men, they might more readily deduce how valid such a recommendation is.

Inspired by satirists like Stephen Colbert, Montgomery is interested in how effective parody might be as a tool to combat bad science. "I've gotten a lot of good reaction" to the website, he said. "I want to see how far can we take this as a joke."

But more than anything, he wants consumers to be wary of the ever-growing number salesmen peddling genetic snake oil.

"We want people to understand which tests are actually useful," he said. "People should be empowered in how they use this data."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter