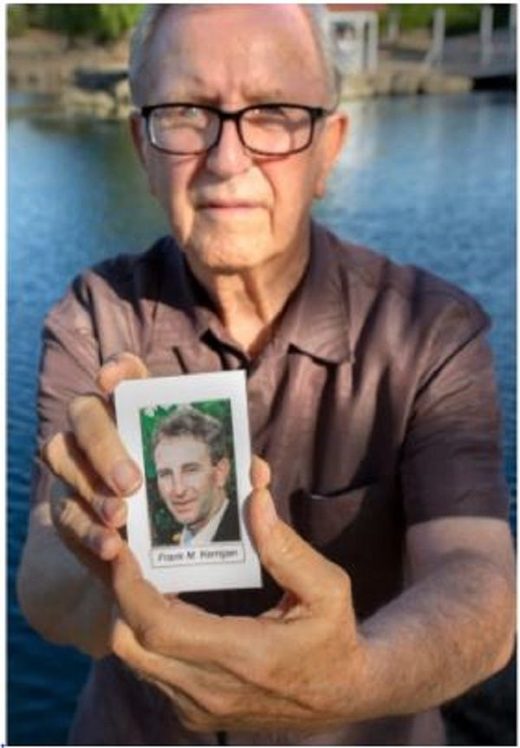

Frank J. Kerrigan, 82, couldn't believe what he was hearing. It was May 23, at night, and he clutched the phone at his home in Wildomar.

On the line was Bill Shinker, a long-time family friend. Shinker also had been a pall bearer, just 11 days earlier, at the funeral of Kerrigan's son, Frank M. Kerrigan.

Only now it seemed that the younger Frank, who was standing on the patio of Shinker's former home in Stanton, had risen from the grave.

"Bill put my son on the phone," Kerrigan recalled. "He said 'Hi Dad'."

It was all part of a bigger mix-up that involved a man found dead in Fountain Valley, a lack of fingerprint records and a mistaken photo I.D.

The mix-up has bewildered the elder Kerrigan, who blames the Orange County Coroner's Office for the confusion.

And it's raised a question:

Since younger Frank is alive, who is buried in his grave?

The ordeal began May 6, when the Riverside County Sheriff's Department told the older Kerrigan to contact the Orange County Coroner. He placed that call and soon was told that his son, who is 57, suffers from mental illness and is homeless, had been found dead behind a Verizon store in Fountain Valley.

Kerrigan says he asked if he should identify the body, but a woman at the coroner's office told him that would be unnecessary since the man had already been identified through fingerprints. However, Kerrigan later learned that apparently wasn't the case.

"When somebody tells me my son is dead, when they have fingerprints, I believe them," he said.

"If he wasn't identified by fingerprints I would been there in heartbeat."

Meanwhile, Frank's sister, 56-year-old Carole Meikle, of Silverado, also learned that her brother had died. She rushed to the Verizon store and was directed to a spot near some bushes where his body was reported to have been found.

Coroner officials had told them that the younger Frank had died peacefully, but that didn't match up with what Meikle saw. "It was a very difficult situation for me to stand at a pretty disturbing scene. There was blood and dirty blankets."

Meikle left a photo of Frank, a candle, flowers and rosary beads at the spot. She hoped to honor her brother.

Later, at Chapman Funeral Home, the elder Kerrigan briefly had the casket opened so that he could take a last look at his son. But Kerrigan was so overcome by grief that he believed he was looking at the younger Frank.

"I took a little look and touched his hair," Kerrigan recalled. "I didn't know what my dead son was going to look like."

Still, all along there were red flags that the dead man wasn't Frank.

Kerrigan said when he received Frank's personal belongings from the Coroner's Office they were in a blue bag instead of the black attache case he always carried. A wallet containing no identification was in the bag, but a watch that was one of the younger Frank's prized possessions, along with a favorite writing pen, were missing.

They held a $20,000 funeral May 12, at Holy Family Catholic Cathedral in Orange. Frank's brother, John Kerrigan, gave the eulogy, and about 50 people came from as far as Las Vegas and Washington State.

"It was a beautiful ceremony," Kerrigan said.

After the services, the body was interred at the Cemetery of the Holy Sepulchre in Orange. That's 150 feet from the spot where Kerrigan's late wife, Catherine Kerrigan, is buried.

Exactly, how the Coroner's Office misidentified Frank isn't clear.

Someone apparently told authorities that the person found outside of the Verizon store looked like the younger Frank, who coincidentally grew up up about two blocks from where the body was found.

Doug Easton, a Costa Mesa attorney hired by Kerrigan, said coroner officials told him they ran the fingerprints of the dead man through a law enforcement database but didn't get a match. They then apparently used an old photo from Frank's driver's license, compared it to the body, and made visual identification, he said.

Meikle added that when her family told county officials that the younger Frank was alive, they were told that authorities had re-entered the man's fingerprints into the database, on June 1, and learned they matched someone else.

The Kerrigan family has been given the man's name from the Coroner's Office, but that identification has not been independently confirmed, said Easton, who plans to file a notice of claim next week against Orange County as a precursor to a lawsuit.

The lawsuit will argue that Frank's civil rights were violated because the Coroner's Office did not make adequate efforts to determine if the body was in fact his because he is homeless.

Orange County Sherrif's Lt. Lane Lagaret, who is a spokesman for the Coroner's Office, declined to comment on the case because an active internal investigation is under way.

Meanwhile, a stranger remains buried in the plot that was suppose to be Frank's final resting place.

"We thought we were burying our brother," said Meikle. "Someone else had a beautiful send off. It's horrific."

She also said Social Security and other federal agencies believe the younger Frank is dead, and are withholding disability payments. The family is working to fix that.

Meanwhile, Meikle said she is thrilled Frank — who has returned to living on the street, declining offers of shelter — is alive. Still, she can't shake the trauma.

"We lived through our worst fear," she said, adding that her brother does not grasp the magnitude of the incident.

"He was dead on the sidewalk. We buried him. Those feelings don't go away."

Reader Comments

lived in Fountain Valley for quite a while... quite a while back....R.C.

P..s, This could have been phrased better: RC