Keltner describes awe most simply as, "Being in the presence of something vast, beyond current understanding." Awe can be inspired by a broad spectrum of stimuli such as panoramic views, being immersed in nature, looking up at the stars, brilliant colors in the sky at sunrise and sunset, remarkable human athletic accomplishments, mind-boggling architectural structures such as skyscrapers or the Egyptian pyramids, breathtaking art, music, etc. The possibilities for experiencing awe are limitless and aren't reserved just for "peak experiences."

In the Living Philosophies anthology, Albert Einstein described the importance of keeping your antennae up and senses open to experience awe. Einstein wrote,

"The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder or stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed."In 2007, Michelle "Lani" Shiota, Dacher Keltner, and Amanda Mossman Steiner (all of UC Berkeley at the time) published, "The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept." In this groundbreaking study, Shiota et al. identified universal subjective descriptions people used to describe a sense of awe. These included:

"Feeling small, insignificant ... the presence of something greater than self ... unaware of day-to-day concerns ... connected with the world around me ... did not want the experience to end."Over the years, Keltner and colleagues have found that people tend to become less self-focused, greedy, materialistic and narrow-minded after experiencing awe. In fact, many of the studies conducted by Keltner et al. have sought to understand why awe arouses altruism of different kinds. The recurrent theme of their research seems to be that awe imbues people with a different sense of themselves...one that is smaller, more humble, and cognizant of being a unique, but insignificant "flea" in a much larger universal scheme.

Paul Piff, currently of the University of California, Irvine worked with Keltner as a student at Berkeley. Since then, Piff has become a thought leader when it comes to awe research. He is particularly interested in the ability of awe to reduce our "it's all about me" egocentric tendencies (myself included) and the constant buzzing and preoccupation with one's self.

The good news is that Piff's research on awe has found that even very short bursts (60 seconds) of episodic awe can shift someone's attention away from the self and cause people to lose themselves in something much bigger than their "small selves."

Piff has discovered that awe seems to "dissolve the self" and promote a type of "self-distancing" that has been observed in other vagal maneuvers that stimulate parasympathetic "tend-and-befriend" responses and prosocial behaviors. Awe also appears to prime the mind to seek more collective interests and breaks the cycle of "us" against "them" divisive thinking.

In 2015, Paul Piff and and Dacher Keltner, along with Pia Dietze, from New York University, Matthew Feinberg from University of Toronto, and Daniel Stancato also from UC Berkeley, published a landmark study, "Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior," in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

For this study, Piff and colleagues used a series of various experiments to examine different aspects of awe. Some of the experiments measured how predisposed someone was to experiencing awe... Others were designed to elicit awe, a neutral state, or another reaction, such as pride or amusement. In the final experiment, the researchers induced awe by placing participants in a forest of towering eucalyptus trees.

After the initial experiments, the participants engaged in an activity designed to measure what psychologists call "prosocial" behaviors or tendencies. Prosocial behavior is described as "positive, helpful, and intended to promote social acceptance and friendship." In every experiment, awe was strongly associated with prosocial behaviors. In a statement, Paul Piff described his research on awe:

"Our investigation indicates that awe, although often fleeting and hard to describe, serves a vital social function. By diminishing the emphasis on the individual self, awe may encourage people to forgo strict self-interest to improve the welfare of others. When experiencing awe, you may not, egocentrically speaking, feel like you're at the center of the world anymore. By shifting attention toward larger entities and diminishing the emphasis on the individual self, we reasoned that awe would trigger tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors that may be costly for you but that benefit and help others."Across a wide range of different elicitors for awe, the researchers identified that experiencing awe made people feel smaller, less self-important, and reduced narcissist, self-serving behaviors. Piff believes that finding ways to create more everyday awe experiences could create a domino effect that leads people from all walks of life to start volunteering to help others, donating more to charity, or making more of an effort to avoid impacting the environment in negative ways.

From a historical perspective, it's exciting to have the latest empirical evidence support the timeless wisdom of people such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who led the Transcendentalism movement of the 19th century and understood the ability of awe to create "oceanic self-transcendence" or what is currently called "self-distancing." In 1836, Emerson wrote in his seminal book Nature, (p. 39):

"Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by blithe air—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me ... I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty."Along this same line, in The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James famously described a secular type of awe inspired "self-transcendence" and how a sense of wonder can play a central role in lifting people out of their mundane sense of the ordinary workaday world. James used language to describe profound awe or when spiritual emotions take center stage in someone's psyche. William James wrote:

"A feeling of being in a wider life than that of this world's selfish little interests; a conviction of the existence of an Ideal Power and a willing self-surrender to its control. An immense elation and freedom, as the outlines of the confining selfhood melt down. A shifting of the emotional Centre towards loving and harmonious affections, towards "yes, yes" and away from "no," where the claims of the non-ego are concerned."Over a century ago, James discussed the idea that the practical consequences of creating the "small self" as Piff would describe in the 21st century were also linked to a "blissful equanimity" free from anxieties, a withdrawal from the material world, and magnanimity towards others.

Why Is Awe Such an Important Emotion from an Evolutionary Perspective?

In 2015, Paul Piff and Dacher Keltner co-wrote an article for The New York Times that tackled the question, "Why Do We Experience Awe?" Piff and Dachner sum up their years of clinically studying awe:

"Our research finds that even brief experiences of awe, such as being amid beautiful tall trees, lead people to feel less narcissistic and entitled and more attuned to the common humanity people share with one another. In the great balancing act of our social lives, between the gratification of self-interest and a concern for others, fleeting experiences of awe redefine the self in terms of the collective, and orient our actions toward the needs of those around us."Lani Shiota is currently a professor of psychology at Arizona State University and is a trailblazing researcher on how our autonomic nervous system and vagus nerve responds to awe. In 2016, she presented a lecture, "How Awe Transforms the Mind and Body" which discusses how the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems respond to experiencing awe.

Shiota is especially curious to explore how the emotions surrounding the experience of awe must have adaptive functions and evolved to influence cognition and behavior in ways that helped our ancestors survive. For example, fear promotes escaping from physical danger and avoiding harmful threats. Love facilitates the close-knit bonds and interdependent relationships on which humans cooperation and community depend.

In a 2011 study, "Feeling Good: Autonomic Nervous System Responding in Five Positive Emotions," Shiota and colleagues found that most positive emotions are arousing and engage the "fight-or-flight" response of the sympathetic nervous system to help someone pursue rewarding goals that feel good. Notably, awe has the opposite effect. Shiota found that awe reduced the sympathetic influence on the heart marked by vagal parasympathetic activation in the vagus nerve.

Additionally, while studying the properties of "awe as an emotion" Shiota found that the facial expression associated with awe were very different from the expressions of other positive emotional constructs such as amusement, contentment, gratitude, interest, joy, love, and pride. Across the study of eight positive emotions, awe was unique because instead of a smile the facial expression included widened eyes, raised inner eyebrows, and a relaxed, open mouth. Shiota concludes that the absence of a smile suggests that awe's function isn't primarily about social affiliation but has different visceral effects.

Most of us are inclined to think that experiencing awe has to involve a personal Everest "wow!" moment that would be classified as a type of peak experiences. But awe can be found in everyday life and may be facilitated by using vagal maneuvers that increase self-distancing and reduce egocentric bias. (Such as speaking to yourself using non-first-person pronouns or narrative expressive journaling that avoids "heart on your sleeve" first-person explanatory styles.)

Long before there was empirical evidence to support the importance of self-distancing, novelist Henry Miller, who was a master of surrealist free association, offered insight on self-distancing and pursuing everyday awe experiences. Miller said, "Develop interest in life as you see it; in people, things, literature, music—the world is so rich, simply throbbing with rich treasures, beautiful souls, and interesting people. Forget yourself. . . The moment one gives close attention to any thing, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself."

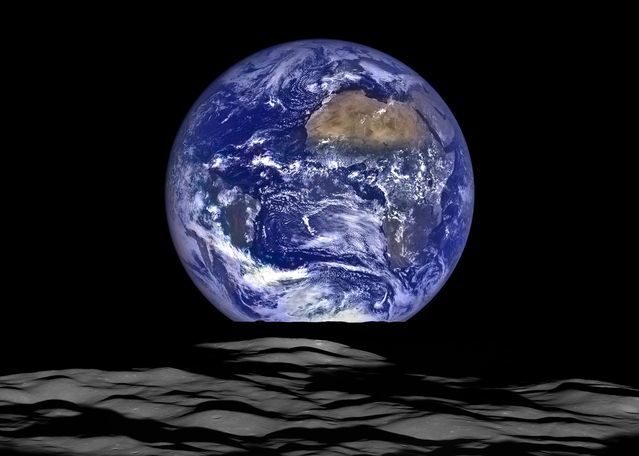

On the opposite end of the spectrum from finding a sense of awe by closely inspecting a blade of grass in your backyard...researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have been examined the life-changing awe called the "overview effect" that astronauts tend to describe after witnessing Earth from outer space. Amongst most astronauts, the overwhelming sense of wonder, and feelings of being a part of a human "oneness" and commonality that is much bigger than one's "small self" corroborates the research of Piff et al.

The 2016 study, "The Overview Effect: Awe and Self-Transcendent Experience in Space Flight" was published in the journal Psychology of Consciousness. David Yaden of Penn's Positive Psychology Center was the lead author of this paper. Yaden and colleagues are studying the overview effect to better understand the emotions astronauts commonly recount and how these might benefit the general population.

In terms of common ways that we can begin to instill everyday experiences of awe into the daily lives of the next generation. A 2014 study, "The Origins of Aesthetic and Spiritual Values in Children's Experience of Nature," found that children who engage in free play, outside, on a regular basis have a higher appreciation for beauty (i.e., balance, symmetry, and color) and more of a sense of wonder (i.e., curiosity, awe, imagination, and creativity).

For this study, Gretel Van Wieren of Michigan State University and her co-researcher Stephen Kellert of Yale University used a blend of research methods that included drawings, diaries, and observation, as well as in-depth conversations with both the children and the parents.

Interestingly, the children in the study expressed feelings of peacefulness and a secular belief that some type of "higher power" had created the natural world around them. The children also reported feeling awestruck and humbled by nature's power, such as storms, while also feeling happy and a sense of belonging in the world. The researchers found that kids who played outside five to 10 hours per week said they felt a spiritual connection with the earth. Children who played outside also felt a stronger obligation to protect the environment than children who spent most of their time indoors.

All too often, the out-of-school programs that might promote a sense of awe for children are being dismantled in lieu of programs that focus solely on crystallized knowledge and standardized testing. Invaluable life lessons learned by running wild and exploring the outside world are sacrificed for strictly cerebral endeavors that take place in sterile "awe-deprived" classrooms.

The study of awe is still a young science. Please stay tuned for more research on this topic and upcoming blog posts in this nine-part Vagus Nerve Survival Guide series.

*This Psychology Today blog post is phase six of a nine-part series called "The Vagus Nerve Survival Guide." The nine vagal maneuvers featured in each of these blog posts are designed to help you utilize your vagus nerve in ways that can reduce stress, anxiety, anger, egocentric bias, and inflammation by activating the "relaxation response" of your parasympathetic nervous system. Recently, "self-distancing" has also been found to improve vagal tone (VT) as indexed by heart rate variability (HRV).

References

Michelle N. Shiota, Dacher Keltner, and Amanda Mossman. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Pages 944-963 | Received 22 Sep 2005, Published online: 19 Jul 2007. Cognition and Emotion. DOI: here

Paul K. Piff, Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, Dacher Keltner. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2015; 108 (6): 883 DOI: here

Michelle N. Shiota, Samantha L. Neufeld, Wan H. Yeung, Stephanie E. Moser, and Elaine F. Perea. Feeling Good: Autonomic Nervous System Responding in Five Positive Emotions. Emotion. 2011, Vol. 11, No. 6. DOI: here

David B. Yaden, Jonathan Iwry, Kelley J. Slack, Johannes C. Eiechstaedt, Yukun Zhao, George E. Vaillant, Andrew B. Newberg. The overview effect: Awe and self-transcendent experience in space flight. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2016; 3 (1): 1 DOI: here

Gretel Van Wieren, Stephen R. Kellert. The Origins of Aesthetic and Spiritual Values in Children's Experience of Nature. Journal of the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, Vol 7, No 3 (2013) DOI: here

Thinking about the uniqueness of life I surmise that many factors work coherently to create this effect: the position of the sun, the planets, the Earth's location is space-time, the leaf, wind-flow, humidity, nutrients in the soil etc. Like a matrix, any difference in the formula changes the outcome.