© National Weather Service

A mind-boggling 751 inches of snow have pummeled the Sugar Bowl ski area near Lake Tahoe this winter. It's emblematic of a record season for precipitation in California's northern Sierra Nevada mountain range, and the abrupt end to a historic drought.

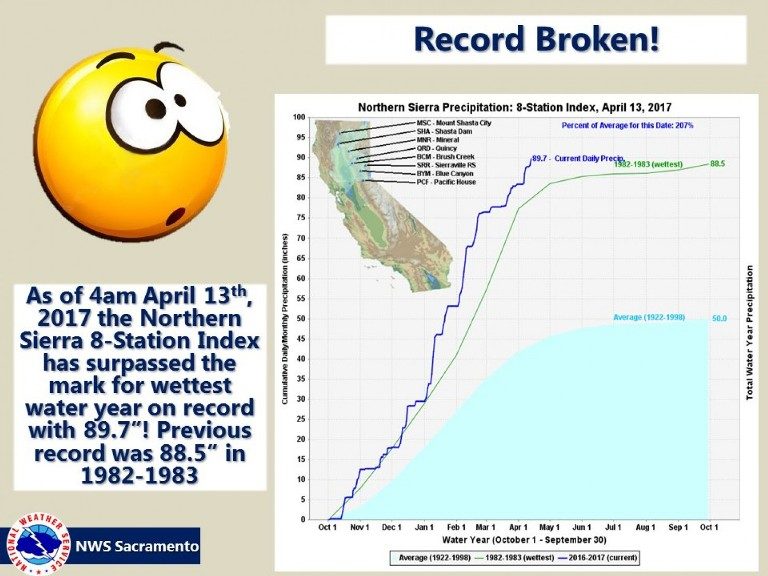

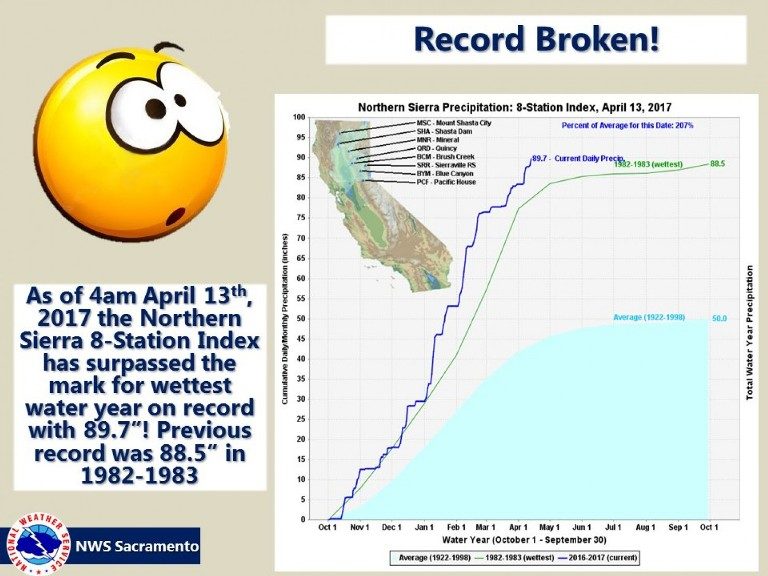

As of Thursday morning, the

northern Sierra had achieved its wettest water year in recorded history, the National Weather Service office in Sacramento

announced.

At eight representative weather stations in the northern Sierra, the average precipitation reached 89.7 inches (combining rain and melted snow), passing the previous record of 88.5 inches set in 1982-1983. And there's plenty of time to add to this record, as the water year, which began Oct. 1, continues until Sept. 30.

The precipitation has come practically nonstop since October. Every single month except November produced above-average amounts.

Ryan Maue, a meteorologist for WeatherBell Analytics,

calculated that the state of California has received the equivalent of 90-trillion gallons of water since October, the greatest volume on record.

In a tweet Wednesday, the Western Regional Climate Center documented more than a dozen individual locations, mostly in the Northern Sierra, having their wettest water years:

In Sacramento, more than

32 inches of rain has fallen this water year, the fourth most since 1877, with time to climb even higher.

The Weather Service described

high-elevation snows as "incredible," with seasonal totals exceeding 600 inches in a number of locations. These amounts are equivalent to snow piling up to the height of a five- or six-story building.

One to five feet of snow has buried the high country in the past week, and

heavy snow was falling in the region again Thursday.

A number of ski areas, including Squaw Valley and Mammoth Mountain, plan to remain open into July.

The phenomena responsible for the onslaught of precipitation are known as atmospheric rivers. Scripps Institution of Oceanography documented 45 cases of these rivers in the sky gushing into the West Coast from the Pacific Ocean between October and March. A large fraction of them made landfall in Northern California, and several were classified as strong or extreme.

What's remarkable is that precipitation this water year outgunned 1982-1983, which featured one of the strongest El Niño events on record. El Niño events tend to tap into abnormally warm ocean waters over the tropical Pacific to intensify precipitation along the West Coast.

Yet there was no El Niño this winter.The quantity of precipitation over the winter stunned forecasters, who failed to predict such amounts in the fall.One theory is that a frigid air mass over Siberia in November set the stage for the tremendous Pacific Ocean storminess. As the Siberian air moved over the Pacific, it cooled ocean temperatures in the North Pacific heading into the winter months. This created a zone of sharp temperature contrast in the Central Pacific, where the storminess developed.

The bountiful precipitation prompted Gov. Jerry Brown to declare California's drought over last Friday.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter