"Calculated misery" sounds like a movie featuring a slow-boil revenge plot — one that involves social media and tears of frustration. Instead, it's the concept that there's money to be made by making an experience so awful that a customer will want to avoid it.

And not only is it sinister, it's profitable — at least when it comes to air travel.

It's common to pay extra for higher-quality products or services. And it's natural to want to pay the lowest possible price for whatever you want or need to buy. That's why many Americans are always looking for the best deal, regardless of what they're shopping for.

That mindset allows airlines to use "calculated misery" to make their baseline products and services so low-quality and unpleasant that lots of people will be willing to pay more to avoid them.

It's easy to name other businesses that would shrivel up and die if they took the "calculated misery" approach.

You wouldn't go back to a barber who purposely gave you a terrible haircut, or who gave you a terrible haircut and then charged you a fee to fix it. And you wouldn't eat at a restaurant where your meal would cost more if you wanted a guarantee that you could sit next to your dining partner.

But the airline industry is a unique beast.

United Airlines' ghastly plane dragging incident has inspired lots of discussion this week about how terrible the flying experience can be, even if you don't get beat up for refusing to leave a seat you've already paid for and been assigned to. It has also sparked a national conversation about how airlines view their customers. And the idea of "calculated misery" plays a key role in that view, because the modern commercial airline industry is uniquely designed to exploit passengers' potential discomfort and anxiety to turn a profit.

"Calculated misery" and you: a match made in budget heaven

The person who coined the phrase "calculated misery" is a man named Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia Law school, an author, and a contributing writer at the New Yorker. His expertise covers topics like net neutrality theory and antitrust law — topics that aren't far removed from his observations about the airline industry.

In 2014, Wu wrote an article for the New Yorker about the decline in quality of commercial airline service. In his eyes, there was an unspoken agreement among the country's biggest airlines to make the flying experience terrible no matter what airline you fly. Wu wrote:

Calculated misery is the reversal of how we usually think about upgrades. Think of going to a restaurant and ordering a burger: Cheese and bacon usually cost extra, and many people will gladly pony up because the gooey cheese and crackling, salty bacon enhance the experience.Here's the thing: in order for fees to work, there needs be something worth paying to avoid. That necessitates, at some level, a strategy that can be described as "calculated misery." Basic service, without fees, must be sufficiently degraded in order to make people want to pay to escape it. And that's where the suffering begins.

With the airline industry, it's the opposite: You're upgrading to avoid hell.

It's like if a burger joint charged you for a patty of plain ground beef and a bun, then gave you the chance to make your burger more palatable by paying a seasoning fee, a medium-rare fee, and separate surcharges for lettuce, tomato, and onion. Or, in airline speak, a seat selection fee, a checked baggage fee, a wifi fee, a preboarding fee, an extra legroom fee, and so on.

In the airline industry, many services and amenities that use to be standard now qualify as an "upgrade." Meanwhile, the "standard" experience is frequently so miserable that many people will pay to make it better.

Here's how calculated misery works when it comes to the size of your airplane seat

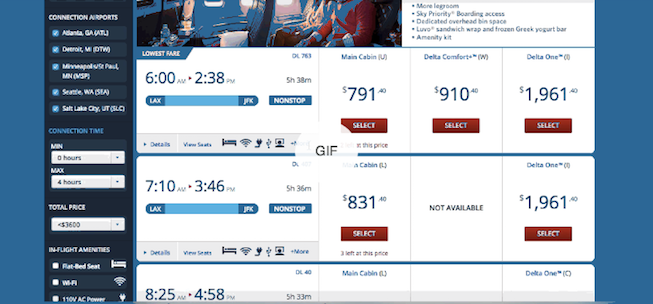

On Delta, if you buy one of the lowest-priced tickets, you have to wait until after checking in to get a seat assignment — the airline calls this fare class "Basic Economy." If you're willing to pay more, you can get a "Main Cabin" ticket that allows you to pick a seat assignment upon purchase. You can also go further, paying still more for a "Delta Comfort" seat with three extra inches of legroom on domestic flights.

From the GIF above, you can see that the price difference between Delta Comfort and Main Cabin ("Basic Economy" wasn't available for my JFK-LAX search) is about three inches of legroom, and the difference between the fares is about $100 — meaning you're paying about $33 per extra inch of legroom.

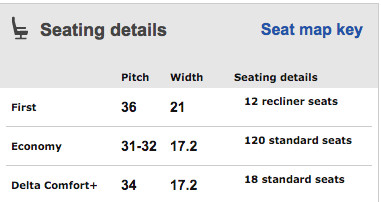

The sinister thing about this is that the pitch of a Delta Comfort seat is 34 inches, which, as USA Today and SeatGuru pointed out in 2014, was seen on some Delta economy flights in 2000.

The shrinkage is real, and we're paying to avoid it.

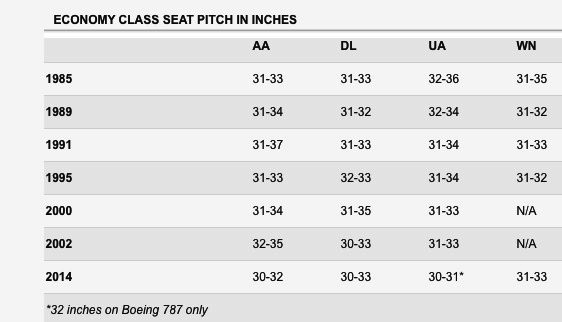

"Seats were 18 inches wide before airline deregulation in the 1970s and have since been whittled to 16 and a half inches," Stephanie Rosenbloom wrote for the New York Times in 2016, reporting on a bill from Tennessee Rep. Steve Cohen that would standardize seat size on airplanes. "Seat pitch used to be 35 inches and has decreased to about 31 inches."

The way Delta and other airlines have lowered their baseline level of service is an example of "calculated misery" at work. Airlines have made the smallest seats even smaller and started selling them for the "basic" fare. At the same time, they've turned what used to be average seats into premium luxuries.

Smaller seats are just one part of this misery. Baggage fees are another example.

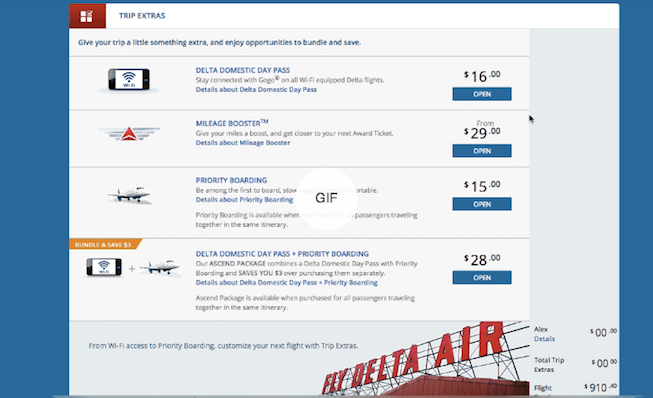

By making people pay for their checked baggage, airlines have put a premium on space in a plane's overhead bins. They, Wu explains, know that people want to avoid paying the checked baggage fee — not to mention the risk that their bags will get lost — and will cram everything into a carry-on. This means more people bring more luggage on board with them, which in turn fills up the overhead bins very quickly, increasing the chances that there won't be any overhead space for the last people to board the plane. The solution? Offer passengers the opportunity to pay a "priority boarding fee" to get on the plane earlier:

Wu believes "calculated misery" also includes things that might not strike us as outright cash grabs. One of the examples he cites is the inefficient way planes board. Studies have shown that boarding in a random order is faster than the methods many airlines currently use, but that hasn't inspired those airlines to change their ways.

The thinking is that if boarding were more efficient and less stressful, there wouldn't be any incentive for people to pay that priority boarding fee.

And even though airlines and the Transportation Security Administration are separate entities, some airlines have tried to profit off long airport security lines by offering expedited security lines to customers who pay a fee (JetBlue calls this service "Even More Speed" and offers it in selected cities).

The ingenuity of "calculated misery" is connected to the overall effect it has on travelers. If someone doesn't pay extra for optional conveniences and upgrades, they might be put in a situation where they have sit far away from their traveling companion, or where they board the plane last and end up checking a bag they had planned to carry on because the overhead bins are full. If the person has a layover, that checked bag might get lost on the way to its destination. And the problems can continue from there.

All it takes is one bad trip to convince someone to cough up the extra money to avoid a repeat. It's not like there are any other options, if all airlines offer equally bad basic tickets and similar experiences. And we'll pay money over and over to avoid it.

Airlines treat you terribly because there's no incentive for them not to

One of the most compelling arguments against "calculated misery" comes from Bloomberg's Megan McArdle. In early 2015, she wrote a rebuttal to Wu, stating that the reason air travel is so harrowing is that customers want the option to save money by only paying for a barebones travel experience:

That makes sense. Thanks to travel aggregator websites designed specifically to help people find the lowest airfares, more Americans can seek out the cheapest plane tickets. Airlines have adjusted for that. But a couple of things have changed in the three years since McCardle offered that rebuttal.Ultimately, the reason airlines cram us into tiny seats and upcharge for everything is that we're out there on Expedia and Kayak, shopping on exactly one dimension: the price of the flight. To win business, airlines have to deliver the absolute lowest fare. And the way to do that is ... to cram us into tiny seats and upcharge for everything. If American consumers were willing to pay more for a better experience, they'd deliver it. We're not, and they don't.

The most pertinent thing: There's no more competition.

My colleague Matt Yglesias points out that there was a point when airlines lost a ton of money, and in order to counteract that, the industry consolidated.

"As of 2013 or so, the post-9/11 losses were so bad that they had wiped out more than 100 percent of all profits incurred by all US-based airlines in history," Yglesias wrote. "The result is a new paradigm in which these big four airlines control more than 80 percent of the American passenger market, with the remaining 20 percent balkanized across a bunch of smaller carriers."

The consolidations occurred around the end of 2014 and beginning of 2015, right when Wu was positing his theory of calculated misery and McArdle wrote her rebuttal. Since then, airlines have rebounded with handsome profits by essentially eliminating competition.

According to BuzzFeed, the US airline industry made an estimated $20 billion in profits in 2016. That's on the back of a good year in 2015, when the commercial airline industry posted record profits. A big part of that success is owed to a decrease in the cost of jet fuel — in 2016, jet fuel prices were a third of what they were in 2014 — which means airlines are operating at a lower cost.

Yet flights are still expensive, signaling that airlines aren't passing on those savings to passengers.

Further, the Department of Transportation reported in May 2016 that bag fees for the previous year totaled some $3.8 billion for the industry, and itinerary change fees brought in another $3 billion — meaning those fees we love to complain about are a substantial source of revenue for the airlines.

The industry's lack of competition is integral to calculated misery, which suggests an implicit collusion regarding deteriorating quality. More competition between individual airlines would combat this deterioration, in the form of some airlines trying to offer a better experience for the same price their competitors charge for a crummier one.

In fact, a company like JetBlue, which at one point was the last holdout to fee-free flying, eventually joined the norm instead of fighting against it. Even Southwest, which still offers free checked bags, charges an EarlyBird Check-in fee for customers who are willing to pay for a better boarding position and is considering adding more fees after missing its revenue goals last year.

If 80 percent of the airline business belongs to a small handful of companies, and what they've shown so far is that they're profitable (sometimes in record-breaking fashion), there's no real incentive to provide consumers with a better flying experience.

The bottom line: Airlines made big money while shoving customer experiences into the gutter. There's very little reason for them to change. The better question might be: Why not just make flying even more miserable?

That approach has already worked out pretty well.

it's not marriage or having children. We need that guy back...I think he was the only one who knew what he was doing, unconditionally.