An American may not be able to grasp what Tim Noakes means to South Africa since no equivalent to Professor Noakes exists in the U.S. In South Africa, Noakes is a nationally famous exercise scientist and physician who has transformed the practice of sport by challenging most commonly held beliefs. And yet, Noakes' own university and colleagues, along with the medical establishment, have suddenly turned against him in what he describes as his "final crusade." Having demolished dogma on subjects as diverse as hydration, motivation and fatigue, Noakes may have gone a step too far. He took on carbs.

On the surface, the Tim Noakes controversy looks like a simple turf war between the renegade scientist and a few South African dietitians. That story goes something like this: in February 2014, the world-renowned exercise physiologist and M.D. tweeted that babies should be weaned onto low-carbohydrate diets. Then Claire Julsing Strydom, the president of South Africa's dietetics association, ADSA, reported Noakes for unprofessional conduct. Noakes chose to fight back and defend his dietary advice even though he no longer practices medicine and could just as well have given up his license. And finally, after dozens of hours of hearings, South Africa's council for health professionals will decide whether Noakes will keep his medical license.

It feels like we've seen this story a thousand times before. Entrenched interests attempt to protect their industry from renegade outsiders empowered by the internet. It looks like the taxi industry vs. Uber, or ACSM vs. CrossFit affiliates. To get any deeper, you have to do a little bit of investigation.

Bill Gifford published a superficial treatment of the Noakes trial in Outside Magazine last month. Gifford attended a hearing in South Africa, saw Claire Strydom break down in tears and wondered, "Is this really the face of the vast pro-carb conspiracy that Noakes seems to think is arrayed against him?" In the field of nutrition, though, things are rarely as they seem. Outside's Gifford apparently did not bother with even the most basic level of research. We did.

We were already familiar with Dr. Noakes from our research on over-drinking in sports. Noakes wrote the most important book on the subject, "Waterlogged." And when CrossFit organized a scientific conference on that topic, we got to know many of Noakes' colleagues. Nonetheless, we never met Dr. Noakes in person during this time.

Last month my CrossFit Inc. colleague Andréa Maria Cecil and I flew to South Africa to interview Dr. Noakes. After around five hours of speaking to Noakes and reading ~300 pages of Marika Sboros' work on the Noakes trial, as well as the opposition's statements, we have discerned a discomforting reality.

The Food Industry is attempting to use Dr. Noakes in order to set an example to anyone who dares challenge its authority in nutrition.

While Noakes may yet win and retain his license, his trial sets a frightening precedent. Anyone who dares to tweet something that is out of synch with the food industry's proxy organizations may face the full force of the junk food industry.

As a highly successful physician, author and professor, Noakes can afford around $150,000 in legal costs and endure endless attacks on his professional reputation. In fact, he seems to revel in the controversy at times. But if this is the price of speaking out against processed carbohydrates, who but Noakes (and CrossFit) can afford it?

It's Not About Claire Strydom or Dietitians

Claire Strydom is the face of the opposition to Noakes, but not its leader. Hers is just one of several complaints made to the Health Professional Council of South Africa against Noakes. HPCSA picked Strydom's complaint out of the bunch, but she had no input in that decision. For example, ADSA's Katie Pereira also filed a complaint against Noakes several months after Strydom did.

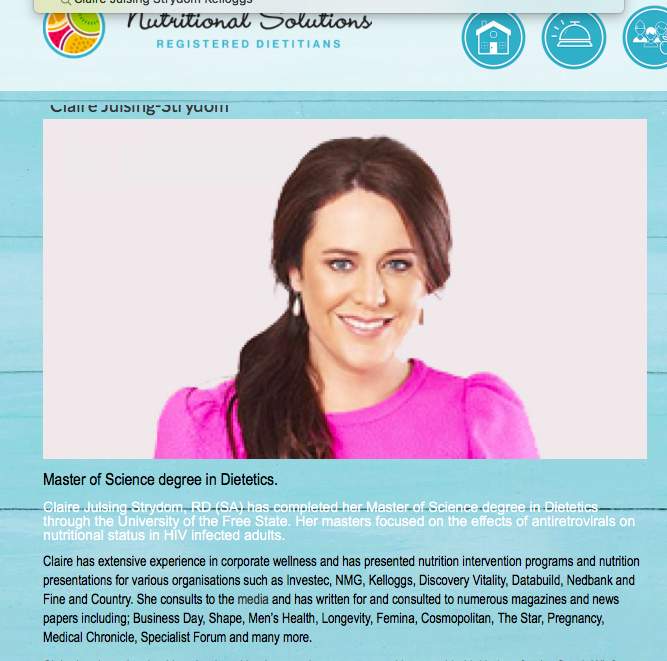

Nor are dietitians as a group truly leading the charge against Noakes. To be sure, Strydom was president of the Association of Dietetics in South Africa when she filed her complaint. But perhaps more importantly, she also is a consultant for Kellogg's.

Since the Noakes trial began, Strydom has erased most online documentation of her Kellogg's relationship. For example, her website once proudly proclaimed her relationship with Kellogg's:

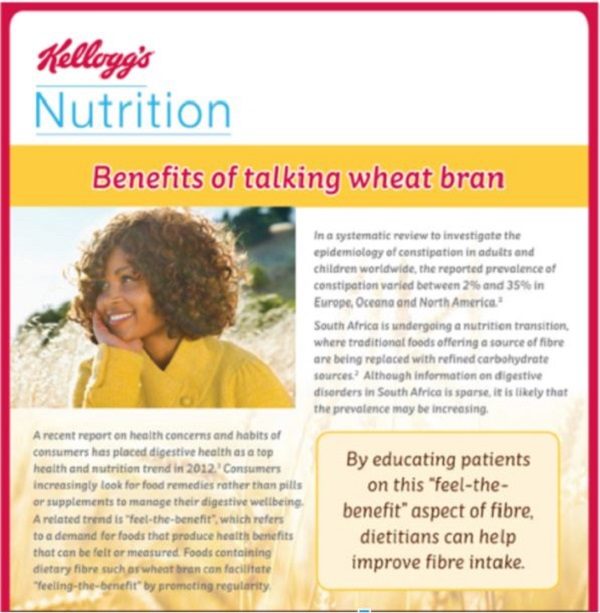

Strydom has come under scrutiny for her Kellogg's ties, her website has become more reticent. It obliquely states, "she consults to the food and pharmaceutical industries." Strydom hasn't erased all the digital evidence, though. We can still see on KelloggsNutrition.com that Kellogg's sponsored Strydom's company, Nutritional Solutions.

Nor is Strydom alone. Besides Strydom, Linda Drummond was Kellogg's "Nutrition and Public Affairs Manager" and on ADSA's membership committee. Cheryl Meyer handled communications for ADSA while consulting for Kellogg's. And Leanne Kiezer managed the treasury and sponsorships for ADSA, in addition to her work as "nutrition assistant" for Kellogg's.

ADSA claims, "we don't believe in endorsing brands to the communities within which we work." Yet they certainly appear to do just that:

Kellogg's ADSA partnership has not generated too much controversy in South Africa outside of the activist community. At least Kellogg's flagship products include a few that regular people might consider healthy, such as Special K and All-Bran. Not so with other ADSA partners.

Over 1/3 of ADSA's revenue comes from its corporate sponsors, including Nestlé, Unilever and Huletts Sugar. Together with the Nutrition Society of South Africa (NSSA), ADSA hosts a yearly Nutrition Congress. Its sponsors read like a "who's who" of Big Pharma and Big Food: GlaxoSmithKline, Discovery Vitality and the Sugar Association, in addition, of course, to Unilever, the Nestlé Nutrition Institute and Kellogg's. Many of these partnerships go back at least a decade.

At the 2014 Nutrition Congress, held Sept. 16-19, a Coca-Cola proxy organization called the International Life Sciences Institute, "contributed to the conference programme, and hosted a plenary session." One doubts this was free.

Strangely, three officials from South Africa's Department of Health spoke at the ILSI session at ADSA's conference: Nutritional Directorate, Gilbert Tshitaudzi; Chief Director of Health Promotion and Nutrition, Lynn Moeng Mahlangu; and Chief Director of Non-Communicable Diseases, Melvyn Freeman. Some of these officials have spoken at other ILSI events as well.

Turning Strydom's Complaint Into the Noakes Trial

After Strydom's complaint in February 2014, HPCSA's Preliminary Committee of Inquiry met on May 22, 2014. What were they to do about this complaint against Noakes? After two days of meeting, the committee failed to come to a decision and opted to reconvene on Sept. 10.

To help make up their minds, the HPCSA committee requested a secret report from Este Vorster, past president of the aforementioned Coca-Cola proxy, the International Life Sciences Institute in South Africa. In her secret report, Vorster mentioned a new meta-analysis that supposedly disproved Noakes' dietary position (Noakes only had the opportunity to see the report when an HPCSA functionary sent it to his attorneys by mistake).

PLOS One had published the new meta-analysis Vorster cited, Carbohydrate versus Isoenergetic Balanced Diets for Reducing Weight and Cardiovascular Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, on July 9, 2014. This meta-analysis become known as the Naude Review, in reference to lead author Celeste Naude. More on the Naude Review later.

Back to the Vorster report. One hanging question was how Strydom could prove Noakes' position was life-threatening and not evidence-based. Vorster responded, saying that they did not need to support this position with "experimental evidence." Instead, Vorster insisted, "reference to the South African paediatric food-based dietary guidelines would be sufficient."

Comment: In other words, "We don't need evidence. Trust us. We're the experts."

Vorster concluded that Noakes "is either not familiar with or does not trust the present South African dietary guidelines." And therefore, Vorster alleged, Noakes "is not qualified to advise on dietary matters." Then Vorster disguised her lead authorship of the guidelines by improperly citing them in her literature section. The published guidelines say they should be cited as "Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS ..." On the other hand, Vorster's report cited her guidelines' author as "Anon."

On the basis of Vorster's report, HPCSA charged Noakes on Sept. 10, 2014, alleging Noakes is guilty of,

"... unprofessional conduct or conduct which, when regard is had to your profession, in that during the period between January 2014 and February 2014 you acted in a manner that is not in accordance with the norms and standards of your profession in that you provided unconventional advice on breastfeeding babies on social networks (tweet/s)."If HPCSA charged Noakes with providing "unconventional advice" on nutrition, then what constitutes conventional advice? In South Africa, the mainstream authority is the country's Food-Based Dietary Guidelines, authored by none other than Este Vorster.

Hence, Vorster convinced the HPCSA to charge Noakes with the alleged offense of disagreeing with her.

But what makes Vorster an actual authority on low-carbohydrate diets, even in South Africa? She has never practiced as a dietitian and admits having never studied low-carbohydrate diets.

South Africa's Dietary Guidelines, by Big Soda and Big Sugar

Big Soda and Big Sugar cooperated to develop South Africa's dietary guidelines. From 1997 to 2001, Este Vorster served as the President of the International Life Sciences Institute, South Africa. Coca-Cola Vice President Alex Malaspina founded ILSI in 1978. ILSI has established itself as the tobacco and junk food industry's most powerful advocacy organization.

It's hard to say where Coca-Cola ends and ILSI starts. Coca-Cola Vice President Rhona Applebaum served as ILSI's President through the end of 2015. ILSI has led the industry's assault on the World Health Organization's tobacco policies, the CDC's chronic disease efforts, and most recently, the dietary guidelines that limit sugar intake.

Besides her ILSI relationship, Vorster maintained ties with the South African Sugar Association, which funded her research (Henceforth we will refer to this organization as the Sugar Association). Vorster continues to serve on the Sugar Association's Scientific Panel. The World Health Organization determined that Vorster's Sugar Association role "could be considered as a conflict of interest" and thus recommended that she "refrain from participating in the specific discussions and decision-making process for developing recommendations and guidelines on free sugars." Yet in South Africa, she enjoys free rein on sugars, and any other topic relating to junk food.

While Vorster presided over ILSI South Africa, she also developed and co-authored South Africa's first dietary guidelines. The food industry's influence on these guidelines is nearly endless. The Sugar Association funded the initial workshop that produced the guidelines. ILSI paid the guidelines' delegates to fly to Zimbabwe to "share the South African experience with eleven other African countries." Penny Love chaired the working group that developed the guidelines. Love consulted for the Sugar Association either during or shortly after this time period, including organizing "symposia" on "sugar and health." Sugar Association public affairs chief Carol Browne served in the working group as well.

Vorster and her ILSI colleague Michael Gibney published South Africa's first dietary guidelines in 2001 in the South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. The release included an article entitled "DEVELOPMENT OF FOOD-BASED DIETARY GUIDELINES FOR SOUTH AFRICA - THE PROCESS." Carol Browne co-authored it, declaring her professional affiliation as "South African Sugar Association, Public Affairs."

The phrase "conflict of interest" is not found in any of the published materials associated with South Africa's 2001 guidelines. Nonetheless, it is ubiquitous in manifestation. Page 17 claims that "foods rich in ... sugars ... prevent chronic diseases by various effects and mechanisms." The following page proposes that "moderate intake of sugar and sugar-rich foods can also provide for a palatable and nutritious diet." Page 21 then alleges, "Sucrose and other sugars have not been directly implicated" in causing diabetes.

Nowhere do the 2001 guidelines recommend limiting sugar intake. Instead they admonish South Africans to "eat fats sparingly." In so doing they emulate the well-trodden industry strategy of shifting the blame from sugar to fat, as Anahad O'Connor has documented in the New York Times.

The "Twin Imperatives" Behind South Africa's Dietary Guidelines

The 2001 guidelines were so transparently influenced by Big Sugar that even industry insiders conceded the problem. As ILSI South Africa trustee Nelia Steyn, a foremost representative and defender of South Africa's nutritional establishment, has explained,

"Members of the Food-based Dietary Guidelines Task Group came from a wide range of organizations; many active participants came from the food industry, even though some had a dual role, in that they also represented their professional association. From the start, the South African Sugar Association played a role and also sponsored workshops."Steyn concludes that South Africa's dietary guidelines were developed according to "twin imperatives: the formulation of appropriate public health policy and the protection of commercial sugar interests." This moment of sincerity is especially remarkable given its source, Nelia Steyn. The Sugar Association funded her research and again, she is a trustee of ILSI South Africa.

South Africa's Department of Health only provisionally accepted the 2001 guidelines, but the department insisted they be edited to include guidelines for sugar consumption. It is telling that government health officials had to resort to this demand while the nation's top nutritionists and dietitians had apparently nothing to say on the topic of limiting sugar.

The government officially adopted the nation's first guidelines in 2003. By then, they warned,

"Eat and drink food and drinks that contain sugar sparingly and not between meals."

Then in 2012, South Africa released a second edition of the Food Based Dietary Guidelines. It was worse.

While Vorster remained involved, this time as lead author, the "technical support" section on sugar was written by Nelia Steyn and Norman Temple. The Sugar Association has funded each of them. They implicitly acknowledged that the previous guidelines had failed to slow the spread of sugar, observing, "The intake of added sugar appears to be increasing steadily across the South African population."

Yet the new guidelines went softer on sugar. They removed the caution not to eat sugar between meals. Instead, they merely recommended using "sugar and foods and drinks high in sugar sparingly." The authors knew that this wording would not effectively slow South Africa's increase in sugar intake.

The "technical support" section for fat intake guidelines similarly suffered from cognitive dissonance. It warned that South African children and others were already eating at the lower bound of recommended fat intake. And thus the authors cautioned that eating fats sparingly could "pose a risk especially when recommended for infants, children and communities with a low fat intake."

In view of this risk to infant and child health, the authors proposed a new, alternative recommendation: "Eat and use the right type of fats and oils in moderation."

Yet somehow their final guidelines rejected this more moderate advice and kept the previous recommendation nearly exactly the same: "Use fats sparingly." The authors did not attempt to explain their decision, which flatly contradicted the data and overall message of their paper. How did they provide "technical support" to fat guidelines they considered risky to infant health?

If people eat a larger share of their diet from fat, they must eat less of something else. Most likely, an increased percentage of fat comes at the expense of carbohydrates. And with Vorster as the guidelines' lead author, fewer carbohydrates must have been an unacceptable outcome.

Not to mention that ADSA requested the industry's involvement in the 2012 guidelines. ADSA chose Sue Cloran specifically in order to represent the food industry's interests in crafting the recommendations. Cloran is a Senior Manager for Nutrition Marketing at Kellogg's, as well as a member of ILSI Europe's Nutrition Requirements Task Force.

The Food Industry's Expert Witnesses

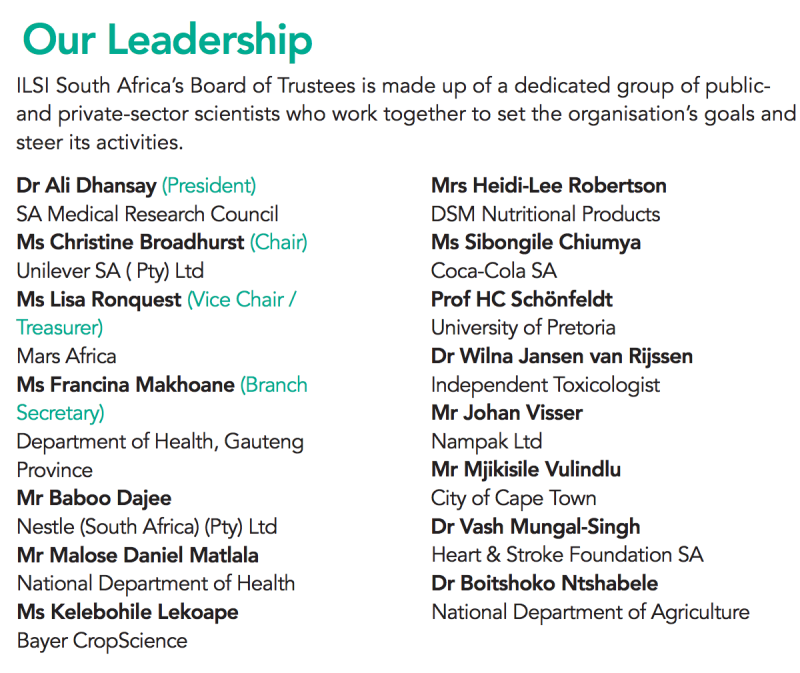

Now that Vorster had convinced the HPCSA to charge Noakes with unprofessional conduct, the hearings began. In November 2015, after a few hiccups, HPCSA summoned its expert witnesses against Noakes: Este Vorster, Ali Dhansay, Salome Kruger and Willie Pienaar. We have covered Vorster's long history with Big Sugar and Big Soda above. It may not surprise you to learn that Dhansay and Kruger are well-connected to junk food as well.

In 2013, Dhansay served as president of Coca-Cola proxy ILSI South Africa. He is currently as president of the NSSA and "Director of Nutritional Intervention Research Unit" at the nation's "Medical Research Council," which is similar to the U.S.'s National Institutes of Health. Hence, the man in charge of nutritional intervention research for the South African government has also presided over an infamous Big Soda and Big Food proxy group.

Note that through his ILSI presidency, Dhansay worked in cooperation with representatives of Coca-Cola, the candy company Mars, the pharmaceutical company Bayer, and Nestlé. Also note that in his role at ILSI, Dhansay presented himself as a representative of South Africa's Medical Research Council (American readers would be remiss to assume their country is immune to the same pathology).

Read more on the Tim Noakes trial here.

The HPCSA sent out its initial press release that caused mass confusion just before 13:00, and only retracted it at 16:20.

"We apologise for incorrectly stating that Prof Tim Noakes was found guilty by the Professional Conduct Committee," the second press release said.

Nice people . . .