Nearly a century ago, five-year-old Kaye Chapman said goodbye to her four brothers and sisters as they rushed out the door of their north-end Halifax home. She collected her Bible and hymnbook and was about to play Sunday school, when a deafening boom swept her off her feet.

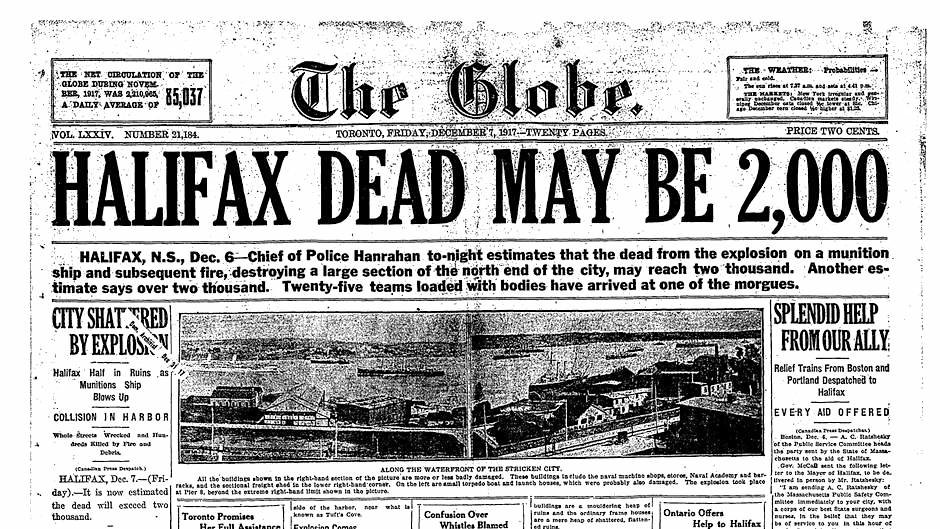

It was Dec. 6, 1917, toward the end of the First World War, when Halifax was the epicentre of the Canadian war effort.

Just before 9 a.m., the French munitions ship Mont-Blanc was arriving in Halifax to join a convoy across the Atlantic. The Norwegian vessel Imo was leaving, en route to New York to pick up relief supplies for battle-weary troops in Belgium. Both vessels were in the tightest section of the harbour when they collided, igniting a blaze that set off the biggest human-caused explosion prior to the atomic bomb.

The Halifax Explosion devastated the north end of the city, killing nearly 2,000 and injuring 9,000. The blast released an explosive force equal to about 2.9 kilotonnes of TNT. Shock waves were felt as far away as Cape Breton and Prince Edward Island. The Mont-Blanc was blown to pieces, its half-tonne anchor shaft landing more than three kilometres away.

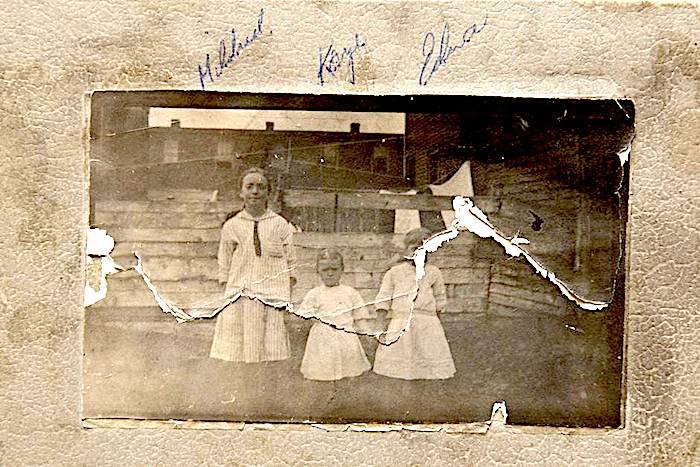

Today, few survivors are left, likely none with the vivid firsthand recall of 104-year-old Mrs. Chapman, who lived on Clifton Street, about two kilometres from ground zero. "As young as I was, I can see everything and I can even tell what we were dressed in," she said at her assisted-living apartment in Saint John. "I had a little white outfit on - a tiny white dress and white stockings."

A series of "roars" erupted around her and Mrs. Chapman flew up in the air and landed between two doors in the entrance of the home, miraculously escaping a shower of glass shards, the flying stove top and crumbling chimney. She lay sobbing and then heard her mother's screams.

At three months pregnant, Alice McLeod was pinned under a buffet hutch in the kitchen where she'd been making a big batch of baked beans for her other daughter Mildred's 13th birthday party. "Wherever you are, stay and don't move," Mrs. Chapman recalls her mother screaming as electric wires sizzled and plaster poured down. Eventually Mrs. McLeod crawled to her young daughter. "We just sat there and held each other for a long time before we moved because we didn't know what to do." (Mrs. Chapman's younger sister, Pearl McLeod, was born the following June.)

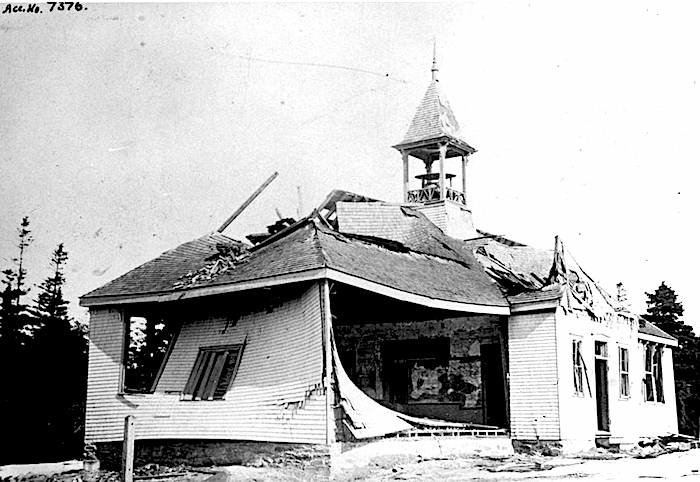

Many children were killed on their way to school that day, or blinded by flying shards of glass. Some returned home to find their houses a pile of rubble, their parents dead or injured in the wreckage.

But lucky for Mrs. Chapman, her siblings had been late for school that day and were also safe, yet shell-shocked under a blown-off veranda two streets away. "They were walking on their way to school. It's a good thing they didn't make it because the school was damaged, too," she said.

Outside Mrs. Chapman's home, a cloud of white smoke rose 3.6 kilometres over the harbour. She remembers a scene of chaos on the street.

"The neighbours all come screaming out of their houses, too. We had to stand where we were because if we went outside, we would've died because everything was electrified," she said. "All you saw was people bleeding here, bleeding there or somebody holding somebody. I saw an awful lot of people holding their animals that were hurt and things like that.

"You know, things that were horrible. You saw that everywhere you looked, it was something bad to see.

Mrs. Chapman's brother Lloyd went in search of their father, Thomas McLeod, a laundry cart driver. He found him unharmed holding back two horses attempting to bolt.

The electricity was shut off and Mrs. Chapman and Mildred were sent to check on their grandmother on nearby Moran Street. "We remember seeing all these people blown up in wagons making for the hospital and, of course, a lot of them never got there. Oh, it was terrible," she said. "All we thought about was getting back to our family."

Everyone, including Mrs. Chapman, assumed Halifax was under German attack, but within the hour, officials knew what had happened.

Initially, there were fears of a second explosion, and people were sent to the Halifax Common, a wide-open green space, for two hours in the bitter cold. Mrs. Chapman ran around to stay warm and loitered inside a makeshift medical tent, where a veteran army physician who had lost an arm in the war bandaged the wounded. Around noon, they were allowed to leave and went home to begin the cleanup. "It was the worst mess. Of course, everything was broken: no heat, no light, no anything," she said.

The next day, a snowstorm blanketed the city, hampering recovery efforts.

In the subsequent days, Mrs. Chapman saw horse-drawn wagons pick up the dead, the body of a young girl dressed in a frilly frock tumble onto the street. She and her siblings went to the relief station for food daily. She recalls being handed a huge parcel that was so heavy she dragged it home by a rope.

"When we opened it, it was a great big fish and Momma was so glad to get it 'cause that was a treat for us. She said 'Look, I'll be able to make some good dinners out of that,'" said Mrs. Chapman. "You got what you could. If you found anything - if it was good, take it, 'cause everybody was taking what they could get their hands on," she said.

Mrs. Chapman can't remember the exact timeline of the aftermath, but said lots of men were around her home helping her family get what they needed. When there weren't enough beds, they wired four chairs together and that's where she slept.

At some point, Mrs. Chapman's family moved in with their grandmother on Moran Street and bought another home on the same street, which is where she lived until she married and moved away from Halifax. "It's hard to think that anything like that could happen," Mrs. Chapman said. "I hope it never happens again. It's a horrible thing."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter