© NASA

Climate change has hit the Arctic

worse than ever over the past few years, but that doesn't mean the Northern Hemisphere is going to be experiencing a mild winter this year.

In fact, a new study shows that the polar vortex is shifting, and it's going to make winters on the east coast of the US and parts of Europe even longer, with exceptionally cold temperatures expected during March.The polar vortex is that lovely zone of cold air that swirls around the Arctic during winter. When parts of the vortex break apart and splinter off, it can cause unseasonably cold conditions in late-winter and early-spring in the Northern Hemisphere.

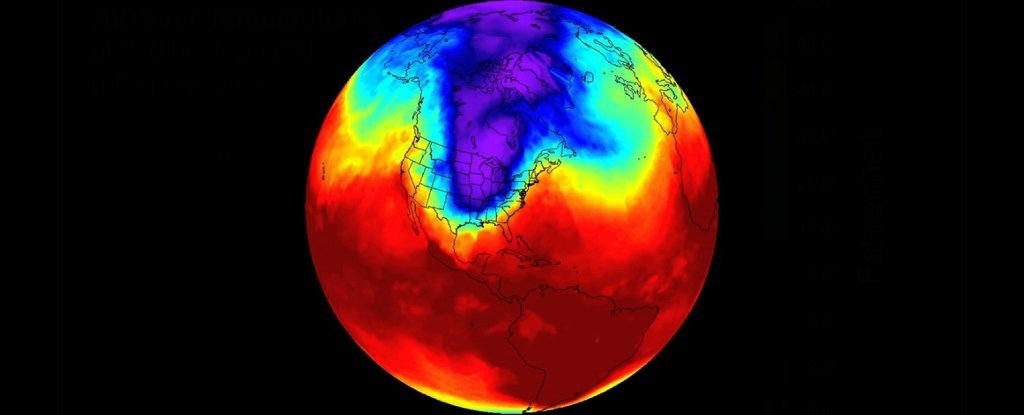

This happened in early 2014 - as you can see in the satellite image above - and caused an

extreme weather event in the northern US and Canada.

But

not many people realise there are actually two polar vortices: the stratospheric polar vortex, which is about 19,800 metres (65,000 feet) above the surface of the Earth; and the tropospheric polar vortex around 5,500 to 9,100 metres (18,000 to 30,000 feet) above the surface.

Usually, when the weather forecasters are talking about the polar vortex, they're referring to the tropospheric vortex, which is the one that rips apart and plunges cold air towards mid-latitude cities, such as New York.

But this study looked at the stratospheric polar vortex, which can have a bigger, but more subtle effect on mid-latitude weather.

After looking at satellite data over the past three decades, the team showed that the stratospheric polar vortex has gradually been moving towards the Eurasian continent, and getting weaker over the past 30 years.That might sound like a good thing for warm weather lovers, but a weaker polar vortex means a vortex that's more likely to break, and those breakages are what send unseasonably late winter blasts of cold air down to the rest of the world.

When the polar vortex is strong, on the other hand, all that cold air gets contained nicely in the Arctic circle where it traditionally is at that time of year.

The weakening of the polar vortex isn't necessarily new - it's something several studies have shown over recent years. But this study also shows that the vortex is moving away from North America and towards Europe and Asia during February each year - and that could cause the east coast of the US to get even colder."The meteorology is complicated, but the study says this shift tends to result in more of a dip in the jet stream over the east coast during March, which leads to colder temperatures," writes

Jason Samenow for The Washington Post.The study also found that this vortex shift is "

closely related" to shrinking sea ice coverage in the Arctic - particularly in the Barents-Kara seas - and increased snow cover over the Eurasian continent.

But that link is still a little tenuous. The main issue here is that researchers have found a correlation, but no one has been able to show exactly how melting ice in the Arctic sea is causing the polar vortex to shift.

"I thought the paper presented adequate evidence to support its conclusions, but obviously one paper is not going to settle an issue," James Screen, a climate scientist at the University of Exeter in the UK, who wasn't involved in the study,

told Samenow."The problem with most if not all of the Arctic/jet stream studies has been the lack of a clear physical cause and effect relationship, with correlations found but mechanisms as yet uncovered,"

added Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric research, who wasn't involved in the study.

The team admits they don't have all the answers just yet, but that the relationship between the polar vortex and Arctic ice loss is worth investigating further."The potential vortex shift in response to persistent sea-ice loss in the future, and its associated climatic impact, deserve attention to better constrain future climate changes,"

they conclude.Unfortunately, researchers will have plenty of opportunity to explore this link this winter, with the temperature around the North Pole 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius)

warmer than it should be right now, and the ice sheets struggling to freeze up.

The research has been published in

Nature Climate Change.

Comment: Se also: