- U.S. could get a blast of cold from north to south in December

- MIT scientist's research contradicts prevailing U.S. forecasts

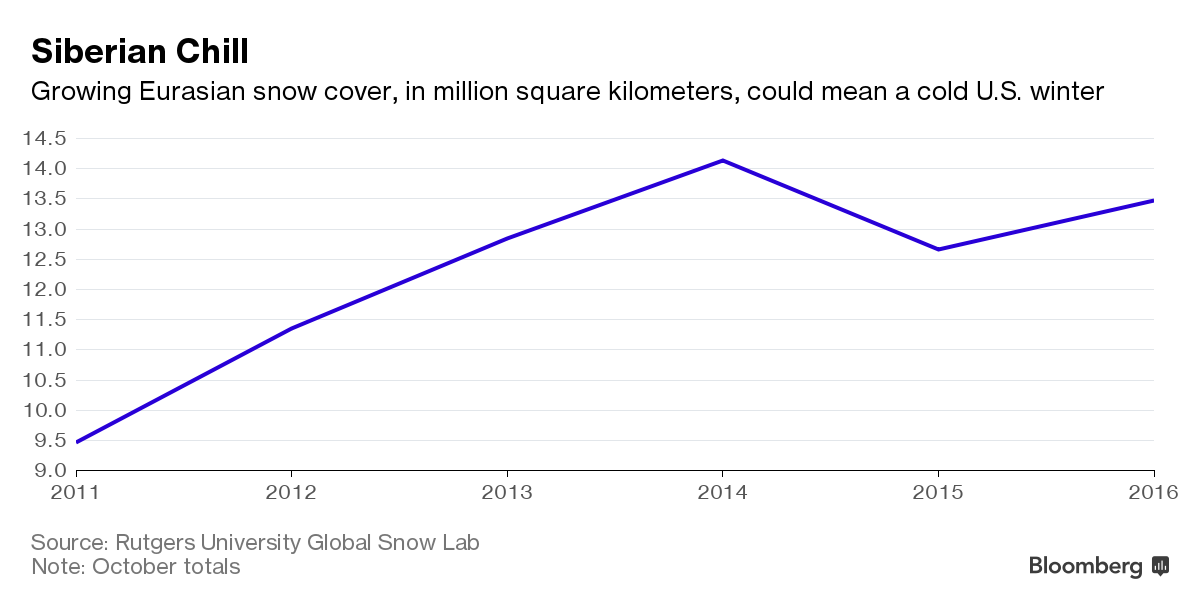

He's the father of the "Siberian Snow Theory." In a nutshell, he argues that the more snow covering the ground in northern Eurasia, the colder we can expect it down below. Sadly, Siberia is looking pretty white already.

Judah Cohen, a renowned MIT climatologist, has been working on this theory for 17 years, despite skepticism from some U.S. government weather experts. Cohen, who figures his theory has been right 75 percent of the time, spies all the makings of an early, cold winter.

"This year, we have had this very textbook situation," Cohen said.

The first blast of Siberian-spurred cold could come in December this year, instead of the usual January, according to Cohen, director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research,a unit of Verisk Analytics, which works with governments and financial-services and insurance companies.

While it isn't certain where the frigid air will land -- North America, Asia or Europe -- Cohen is predicting cold will envelop more of the U.S. than government forecasters expect. Cold, rain and snow could extend from the upper Great Plains to Florida.

Holiday travelers will hope he is wrong, as will retailers who rely on last-minute shoppers who could be deterred by snow and slush. But those who make money from natural gas, whose price dropped because of warm weather, may be in for a treat.

"If he is right that would be terrific," said Teri Viswanath, managing director for natural gas at Pira Energy Group in New York. "I hope he's right."

Conflicting Forecasts

Viswanath isn't betting on it because of conflicting weather models. For example, the Tuesday forecast for Dec. 2 to Dec. 6 called for much of Canada and the eastern U.S. to be warmer than normal, according to MDA Weather Services in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

Since he was a graduate student, Cohen, who grew up in Brooklyn, has explored the connection between snow in Siberia and weather throughout the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere.

Cohen charts a kind of chain reaction. Climate change melts ice in the Arctic Ocean, resulting in more moisture in the atmosphere. That leads to more snow covering Siberia, which reflects sunlight -- and warmth -- from the terrain.

This chill sends energy toward the Polar vortex, the vast weather system that traps cold air in the Arctic. As a result, the vortex breaks down, sending cold air south, as if a refrigerator door had opened.

1998 Fail

Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the U.S. Climate Prediction Center in College Park, Maryland, isn't convinced. In a conference call last week to discuss federal forecasts, he called the correlation between Siberian weather and the U.S. "weak."

On the commercial forecasting side, Matt Rogers, president of Commodity Weather Group LLC, brings up the inconvenient fact of 1998. Blame El Nino, the periodic warming of the Pacific Ocean that often wreaks havoc with global weather.

That year, after that disruption, snow piled up in Siberia -- but the U.S. winter was warm. Last year -- the warmest winter on record in the contiguous 48 states, Cohen's theory missed again because of El Nino.

"So I think his Siberian-based prediction could work out, but a 1998 fail is still a huge risk," Rogers said.

Comment: The signs are already here, with early snowfalls and cold records already being set: