The Mosaic Distinction... Psychopathy in action.

With increasing clarity scholars of history and religion are coming to perceive a disturbing trifecta--

a nexus that links monotheism, intolerance, and violence. Today the jihadists are the most prominent exponents of this noxious triad. As will be seen below, however,

the Hebrew Bible is the originating locus.

To be sure, violence is a human universal. To take an extreme example, consider the wars conducted by the Aztecs to procure victims for their rituals of human sacrifice. These conflicts were bloody, but they were not undertaken to maintain and extend an intolerant monotheistic faith. The Aztecs were quite content to leave the polytheistic beliefs of their own nation, and those of their neighbors, just as they were.

Matters were different among the ancient Israelites. As the Egyptologist Jan Assmann notes: "[t]he accounts of the Exodus from Egypt, violently forced upon Pharaoh by God-sent plagues--and even more so the conquest in Canaan--depict the birth of the Israelite nation and the rise of monotheism (these two being aspects of the same process) in terms of extreme violence." The prominent place of these motifs in the historical memory of the people who created the Hebrew Bible makes them highly significant.

In addition to the glorification of violence, these narrative reveal a demonization of the Egyptians and the Canaanites. And demonization is often a prelude to aggression.

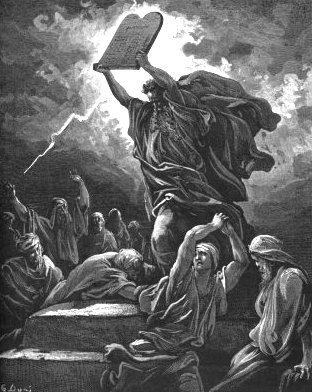

Violence also figured as a technique for internal control, among the Israelite population itself. In the aftermath of the Golden Calf episode, some 3000 individuals were slain ("each man kill his brother, and each man his fellow, and each man his kin"; Exodus 32:27-28). In another passage death is prescribed for those who might dare even to suggest a return to idolatry: "you shall strike him and he shall die, for he thought to thrust you away from the Lord your God." (Deuteronomy13:10).

Violence is also visited on those who would fraternize with neighboring people. For the crime of associating with Moabites and Midianites, 24,000 were slain. (Numbers 25 1-11).

Extreme violence marked the campaign against the cities of Canaan, where nothing was to be left alive.

The ancient Israelites invented ethnic cleansing.All in all, scholars have enumerated some 600 passages linking violence with the origin and propagation Israelite monotheism. To be sure, minimalists and others have questioned the historicity of of these accounts. To cite a recent essay by Niels Peter Lemche: "The exodus has a long time ago passed from history into fiction.

It never happened. Neither did the conquest ever happen. Several biblical scholars including myself have made this clear. From an historical point of view, the Israelites could not have conquered Canaan by destroying Canaanite forces, for the simple reason that the Egyptians still ruled Canaan when Joshua is supposed to have arrived, i.e. shortly before 1200 BCE. Secondly, there is no trace of foreign immigration, and thirdly, even the biblical account about the conquest is contradictory (compare Joshua with Judges 1)."

Granting (as I think we must) these points, there remains this question:

why would any people seek proudly to remember the atrocities I have just cited, parading them seriatim in their most sacred text, the Torah? And of course, some details of the accounts are likely to have been true. For the victims it looks very much as if the Torah scrolls were the scrolls of agony.

The conclusion is severe but inescapable.

This nexus of violence, intolerance, and monotheism bears a clear stamp of origin: Made in Ancient Israel. Some seek to mitigate this harsh judgment by observing that after the rise of Christianity and Islam--the hyperpowers of monotheism as it unfolded in the course of history--Jews did not engage in these types of repression. Just so. But was it because they wouldn't, or because they couldn't?

Now Jews do have power in the state of Israel, and it is a very powerful state indeed.

The Israeli government has been drawing on the ancient prototypes, by practicing violence and ethnic cleansing on the Palestinians. Ethnic cleansing? Well, what else can one call the massive land grab in the West Bank? To be fair,

Israeli peace groups have been at the forefront of documenting and opposing this misbehavior. They

represent the best aspects of the prophetic movement that has also radiated throughout the Abrahamic tradition. But the

fons et origo of the trifecta is clear.

One must also recognize that today secular Jewish scholars are at the forefront in exploring and exposing the sorry record of monotheism in these realms. One is Professor Regina M. Schwartz, author of

The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism (University of Chicago Press, 1997). This hard-hitting monograph stems from a question posed to Schwartz when she was teaching the Bible to undergraduates: "What about the Canaanites?" In her view, biblical narrative has been a singularly powerful form of social memory. Too much theological reflection, Schwartz believes seeks simply to close the "old monotheistic" book, and leave things as they are. After all, we are told, the Bible is the word of God. (What kind of god is of course a question too rarely asked.) In a positive message, Schwartz seeks to open the scriptures to the possibility of multiplicity so that, as she puts it, "new books may be fruitful and multiply." Hers is an invitation to an ethic of possibility, plenitude, and generosity, a welcome antidote to violence. In this way her study is as important for its insights into memory, identity, and place as for its criticism of monotheism's violent legacy.

Jonathan Kirsch, an attorney and book columnist for the

Los Angeles Times, has written

God against the Gods: The History of the War between Monotheism and Polytheism (Viking 2004). In this wide-ranging survey Kirsch points out, correctly, that the earliest impulses toward monotheism can be found in Egypt with pharaoh Akhenaten's forceful attempt to move the nation to the worship of one god, the Aten. Yet this reform lasted at most seventeen years, and efforts to connect it with Moses remain problematic. In fact, Akhenaten's religion left no progeny; the Israelite project definitely did.

After reviewing the evidence from the Hebrew Bible, Kirsch demonstrates that monotheism gained momentum with the development of Christianity which became dominant in the Roman empire under the emperor Constantine. Interestingly, Kirsch shows that the conflict between the worship of many gods and the worship of one true god never disappeared from the lives of Israelites, Jews, or Christians, despite many historians' claims to the contrary.

Conventionally and obsessively, monotheists decry polytheism ("paganism," "heathendom"). One reason for such dismissals may be that in some ways polytheism is more reasonable, making it a dangerous rival. "At the heart of polytheism is an open-minded and easygoing approach to religious belief and practice," he asserts, the opposite of monotheism's dangerous "tendency to regard one's own rituals and practices as the only proper way to worship the one true god." Kirsch's comparison is perhaps overdrawn, but it is worth pondering.

While he does not claim originality,

Kirsch clearly shows that monotheistic religions have too often used the worship of one god as a pretext to persecute those who do not share such beliefs. He demonstrates the ways in which this conflict gave rise to the tensions that exist even within monotheistic religions today.

Well, that's enough to turn many people off of religion completely. It is amazing that the Old Testament is the foundation of Judaism, Christianity and Islam; religions practiced by half the people on Earth, maybe more.

You ever read the Quran [Link] ? If you are a die-hard Hebrew or Christian you are probably saying 'No darn way', which is understandable given the narrow field of view you are allowed, yet it is a beautiful document which expounds upon Old Testament and Torah stories. One thing you are missing if you've not read it is the admonition following each surah about defending the faith, which reads; '...yet it is better to forgive, if you but knew it."

Wahhabi (Sunni) [Link] versions don't include that part, which is why they are making the news and helping you to fear Islam.