She considers the perspective that tattoo acquisition can be adaptive behaviour or a process addiction and considers what conclusions can be arrived at by studying it in detail

'Our wounds serve to remind us where we have been they need not dictate where we are going" (Davis & Dunkle, 2009).

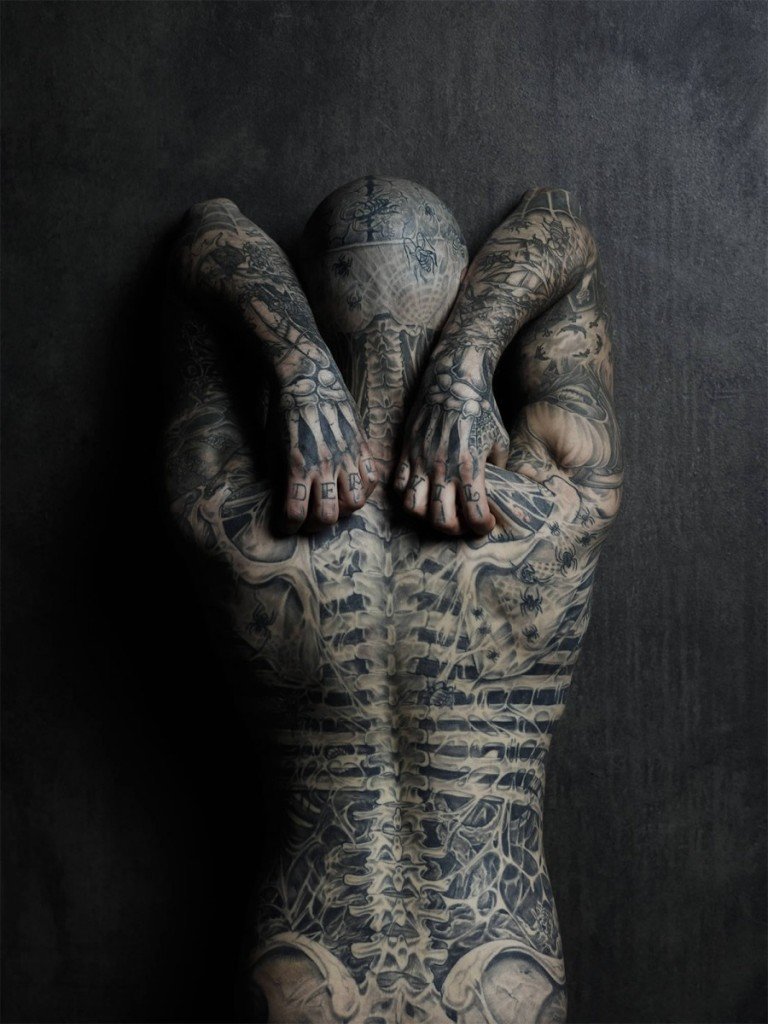

For centuries, sub-cultures ranging from ancient warriors to those on the fringes of society have organised themselves around symbols etched into their skin. Tattoos are ritualistic, permanent and defining. They are seen as an unspoken symbolic language that are said to echo the experiences of the individual by way of coded messages hidden within layers of imagery.

As society becomes increasingly tattoo-acceptant, tattoo acquisition is fast becoming a growing phenomenon amongst individuals of all socio-demographic backgrounds. Consequently, the number of individuals who express themselves through the symbolism within tattoos to the detriment of self could also be on the increase. Therefore, greater understanding of their prevalence and the concept of tattoo acquisition as an adaptive behaviour or process addiction may prove useful and have implications in terms of treatment and prevention strategies.

Western culture assumes that adult behaviour is rooted in childhood. In the clinically based model of Developmental Immaturity, Mellody (2003) postulates the nature of a child at birth is of a precious ego state, in that children are born: precious just as they are; can expect protection; are human and make mistakes, as such are seen as being perfectly imperfect; dependent upon others for their needs and wants, and need containment. Children obtain their sense of identity by internalising or introjecting the caregivers' perceptions of and beliefs about the child. In order for children to arrive in adulthood as mature functional adults, each characteristic needs to be developed by a major caregiver.

Any behaviour exacted upon a child that is less-than-nurturing,[1] is defined by Mellody as trauma, which may cause developmental immaturity, equally shaping a child's relationship with self, others and their environment. Individuals may grow physically and chronologically, yet remain childlike, and it is these wounds that drive their vertical rather than horizontal adult behaviours. Relationally traumatised individuals experience difficulties with: esteeming themselves from the idea of inherent self-worth; protecting and nurturing themselves, being real, understanding their own needs and wants, and living life with an attitude of moderation in all things. If an individual does not have a respectful, affirming relationship with self, relationships with others automatically become dysfunctional and maladaptive. Such individuals are prone to develop addictions, mood disorders and physical illness.

According to the model, addiction problems usually manifest themselves as a means to attempt to medicate unwanted reality, create intensity or to alleviate pain. It recognises that any substance or process, perceived as relieving distress can become an addiction. Thus addiction is seen as a symptom of developmental immaturity as a consequence of childhood trauma (Mellody, 2003).

Potential relationships between individual developmental pathways, trauma and tattooing have been revealed in a study I conducted as part of a research project carried out London South Bank University. The research involved thematic analysis of interviews with heavily tattooed individuals who identified as aesthetic, committed but concealed or committed collectors[2] . The aim was to garner an understanding of how tattoo acquisition might mirror the addictive process in terms of presenting a compulsive and obsessive pattern of behaviour, engaged in to the detriment of self. Interviews were conducted with twelve amateur and modern professionally[3] tattooed adults, aged between 20 and 47, and varying in culture, gender, profession, sexual orientation, and socio-demographic background.

Family of Origin

The interviews revealed a number of patterns in how Family of Origin - early relationships and experiences with primary caregivers, whether positive or negative - contributed to or inhibited the participants' psychological development, and in how adverse life events influenced their developmental pathways. Though almost all the participants interviewed experienced a conventional parental setting during their early, formative years, half experienced parental divorce during childhood and were subsequently raised for significant periods by single-parent caregivers. Of those who experienced conventional parenting, more than half described what each viewed as a less-than-nurturing parental template, with only one of whose parent's remained married. Fewer participants reported a nurturing or neutral template; loss of a parent through death, divorce or estrangement was a common theme.

Of course, starting on a less-than-nurturing pathway does not guarantee arrival at a particular destination - addictive behaviour - but it does make it more probable. However, it would appear that the further down a less-than-nurturing pathway a participant travelled, the greater the probability became. Adverse life events emerged as a variable influencing the developmental pathway followed.

Adverse Life Events

All participants described experiencing some sort of adverse life event, including emotional, physical and/or sexual neglect/abuse during their life, often - though not always - by a primary caregiver. Some described experiencing emotional and physical neglect/ abuse as a consequence of their primary caregivers; whilst others experienced sexual abuse not directly as a consequence of their primary caregivers. Household Dysfunction was also commonly described, such as witnessing a household family member treated violently, household substance abuse by a primary caregiver or mental/physical illness in the household. Half of the participants had also experienced institutions. The model suggests that childhood abandonment, neglect, abuse and exposure to other traumatic stressors are risk factors for addictive behaviour (Mellody, 2003).

Function of Tattoos

Most participants sought and obtained their first tattoo during adolescence (13-21), supporting the widely held view that initial tattoo acquisition, in the modern, mainly Western and typically collectivist societies from which these individuals are drawn, usually function at some level as an adolescent rite of passage, as individuals struggle for identity and control over their changing bodies. Half described their initial tattoo acquisition explicitly as a rite of passage; although some did not articulate the link explicitly, in their descriptions of themselves in adolescence, it appeared to be implicit.

Given half the participants described their initial tattoo acquisition as an adolescent rite of passage; we might expect that cessation would occur upon execution. However what began to emerge was a suggestion that although stimulated by environmental features, tattoo acquisition served other functions, namely as; an anchor, mask and symbol of change, irrespective of a transitional milestone.

Some participants discussed conceptualising the tattoo as an anchor, marking special memories of stability, in stark contrast to the nomadic upbringings their primary caregivers provided. Some developed the concept of tattoo as a mask, either charting the progression from drawing on paper, to dolls and eventually their own skin as a natural one; to emulating the personas of aggressive, muscular tattooed men within the community as a means to protect against and/or incite violence. Others acquired commemorative tattoos after sudden and unexpected familial deaths. Unable to synthesise the trauma owing to its sadness and enormity tattoos were used as a means to externalise grief and mark changes visually and symbolically.

Although each participant travelled their own wounded path to tattoo acquisition, the common denominator was the exclusion/preclusion of an in-group as consequence of less-than-nurturing parenting, adverse life events and the embracement of the sub-culture of tattoos to dissociate from mainstream society and form allegiances with an out-group - adaptive behaviour. Their tattoos served different functions and five, albeit overlapping strategies were identified as follows: tattoos as a means to control, change feelings, mask, self-harm/coping strategy and alexithymia (the inability to identify and describe feelings in the self). It also appeared that as a participant's tattoo process progressed in intensity and frequency, the functions tattooing served for them also increased

Negative control issues are seen as a maladaptive-behaviour often in response to dysfunctional parenting (Mellody, 2003). Some participants voiced the function of their tattoos was specifically to control their physical appearance and spoke of the pleasure they experienced by determining another's reality. Others described using tattoos as a means to alleviate their own reality, by way of euphoria or displacement. Further along this continuum were participants who described self-harming as a means of to alleviate internalised shame or symptoms of mental health. They charted their progression from self-harming to tattoo acquisition in terms of a perceived positive emotional regulation strategy.

Of the participants who described the function of their tattoos as alexithymia, all had experienced significant adverse life events during their lifespan which they unable to process or articulate verbally. In the absence of language in which to vocalise and process their trauma, all participants acquired tattoos as a means of creating a new narrative by marking the absence and filling the voice, which can aid healing (Caruth 1996). Of the participants who described the function of tattoos as a mask, all experienced severe abandonment, neglect or abuse. Participants described their tattoos as a symbolic mask developed in response to the systematic abuse they received and the crippling shame experienced as a result.

Although each participant operated from a different motivational position the principal was fundamentally the same: presentation of a false self in which to protect the wounded self. It is here we begin to see how tattoos might mirror an addictive process by initially appearing to be an adaptive behaviour that transgresses into a pathological relationship that has life damaging consequences.

Given that the majority of participants acquired their initial tattoo in adolescence, at time of interview, with an age range of 20 to 47 including five in their 40's, five in their 30's and two in their 20's, - all participants were heavily tattooed and confirmed they would they would acquire further tattoos. More than half cited no intention of cessation until such a time they either ran out of skin or covered up previous tattoos, indicative of both escalation and intensity. Perhaps the most overt evidence of tattooing to detriment to self was the impact a participant's tattoos had on society in terms of how they were perceived, received and in deterioration/loss of relationships.

Conclusion

This research was conducted on the premise that tattooing could potentially be seen as an addictive behaviour and that trauma lay at the heart of its foundation. Although, the who, whys and wherefores remained a mystery until a narrative of abuse unfolded from 12 unknown individuals from all socio-demographic backgrounds. The commonality amongst the participants was one of developmental immaturity as a consequence of being relationally traumatised by a primary caregiver, often compounded by significant adverse life events. Tattoos can be seen as a symbolic version of the storied self through which individuals can communicate their identities and experiences, including that of trauma. Little wonder, given that a participant's development was generally arrested during their formative years that their narrative become one of visual imagery, albeit etched onto a living canvas. By figuring out the origin of an individual's symbolic narrative, a physiological road map can be created and the blanks filled in.

For some discourse becomes symbolic, although perhaps not in the sense one would initially assume. For some it is the act of tattooing that is of importance, in terms of metaphorically and symbolically seizing control over a situation for which they initially had none. In essence self-mutilation by proxy but in a seemingly life affirming way. Whilst the functions of tattoos serve many purposes each derived from a separate motivation/wound, the common theme is that they serve as a banner of abuse and neglect, in terms of 'judge me for what I have done to myself, (mask), not for what has been done to me (abuse).' This could have important implications for clinicians in terms of employing alternative means of communication through visual imagery which could aid the therapeutic alliance and create a new life-affirming narrative, devoid of permanent ink.

References

- Caruth, C. (1996). Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Davis, J, & Dunkle, R.A.(2009). The Slave of Duty. Criminal Minds. Los Angeles: CBS Television Studios.

- Goldstein, N. (2007). Tattoos defined. Clinics in Dermatology, 25(4), pp. 417-420

- ·Mellody, P. (1993). Post Induction Therapy

- ·Mellody, P. (2003). Facing Co dependence, What It Is, Where It Comes From, How It Sabotages Our Lives. New York: Harper Collins

- Goulding, C, Follett, J, Saren, et el. Process and Meaning in ' Getting a Tattoo' Advances in Consumer Research (2004). Volume: 31, Issue: 1, Pages: 279-284

- [1] Less-than-nurturing behaviours may come in the form of enmeshment, neglect, abandonment and/or abuse (Mellody, 2003).

- [2] Tattoo acquisition can be divided into three categories: Fashion and aesthetic: Committed but concealed, and Committed collectors (Goulding, C, Follett, J, Saren, et el 2004).

- [3] There are five identifiable tattoo types; traumatic, amateur, professional (cultural and modern tattoos), medical and cosmetic.

the issue of toxicity of the inks? I've read the inks used in the US, in particular, are far from non-toxic.

Depositing a long lasting toxic substance in a sub-dermal layer is just begging for some health issues.

Seems like discussing the risks, whether implicit in the process or avoidable is done wisely, is an essential part of reviewing the tattoo experience.