Thanks to the public uproar, we'll never know whether the "ice-minus" bacteria would've have wrought catastrophe or simply protected strawberries from frost, as its creators intended. But scientists remained interested in harnessing the ability to manipulate ice. Recently, a group of researchers uncovered what they believe is the secret to its special talent, which they hope will enable them to create nanotechnologies that mimic it — ice-minus, minus the supposed risk.

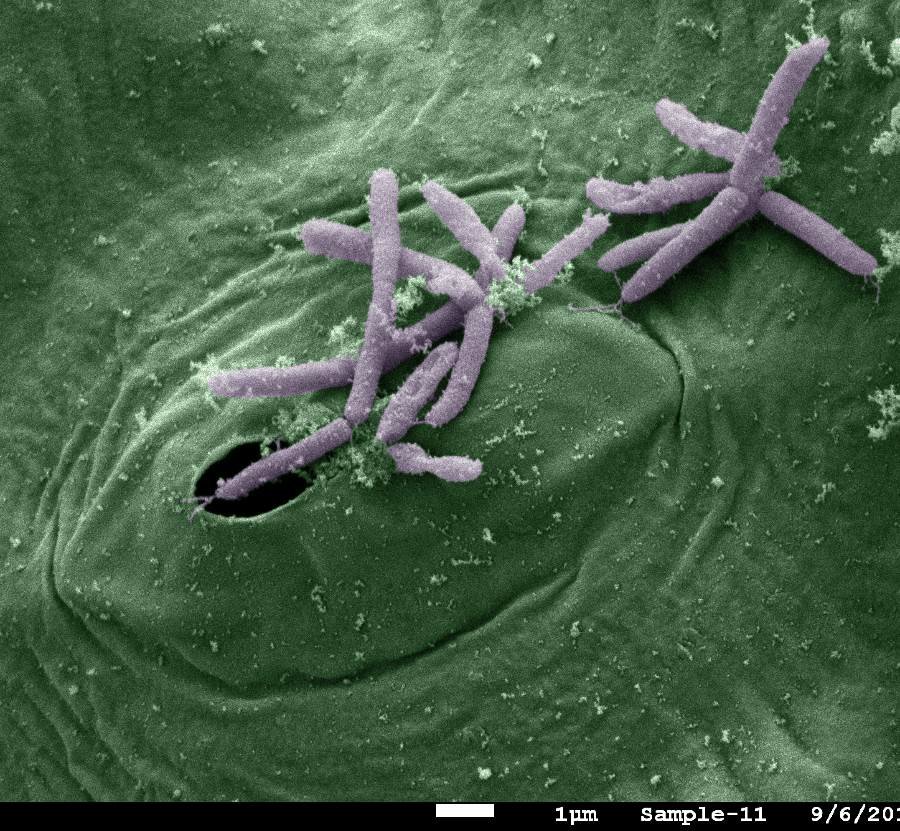

Pseudomonas syringae and other species of bacteria that induce ice to form around them (thus "ice-nucleating" bacteria) are found all over the world, and cause significant crop damage. Impurities in water usually prevent it from freezing until about 25 degrees Fahrenheit, but the bacteria can push the freezing point back toward 32 degrees Fahrenheit (zero degrees Celsius). The ice crystals that form in turn burst plant cell walls, letting the bacteria feed on nutrients from inside the cells. Wind carries the bacteria into the atmosphere, spreading it to new sources of food.

Ice-nucleating bacteria are pretty much everywhere: in the air, water, plants, mountains, valleys, Antarctica. Scientists think its ability to encourage ice growth may also play a significant role in the weather, providing nuclei for cloud formation, raindrops, and snowflakes, and could be a big part of why the Amazon is so rainy.

Tobias Weidner, a bioengineer at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, Germany, led the team of researchers who believe they've figured out how the bacteria does it. They looked at P. syringae's molecular structure through a spectrometer, which allowed them to see how the bacteria's surface interacts with water molecules. Previously, Weidner says, many scientists thought that the bacteria's surface mimicked the structure of ice crystals, encouraging free-roaming water molecules to fall into an icy lattice. Instead, they found, the bacteria's surface forms a pattern of water-attracting (hydrophilic) and water-repelling (hydrophobic) areas. These push and pull on the water molecules they touch, creating high- and low-density zones that prompt the molecules to arrange themselves into a crystal pattern.

From a technological point of view, that's good news. Artificially mimicking the molecular structure of ice would be difficult, Weidner says, but creating tiny striped hydrophobic and - phyllic strips using an artificial polymer might be doable. "That's something we could mimic in a nanofabrication lab," he says. "It's maybe just as simple as mimicking these patchy surfaces."

The ability to precisely control the formation of ice could have many useful applications, Weidner says — everything from refrigerators and frozen food processing to improved cryogenics.

Some varieties of P. syringae — including the modified "ice-minus" version — lower the freezing point of water, and it might be possible to mimic that type, too, Weidner says. "Maybe if we get lucky, it goes both ways." This could be even more useful, perhaps leading to anti-ice coatings for things like airplane propellers or telephone lines.

Because P. syringae's molecular structure promotes ice formation, the bacteria itself doesn't have to be alive to be useful; Snowmax kills the bacteria that are used to make artificial snow to prevent possible environmental harm.

The bacteria has another trick, though, Weidner's team found. When water molecules rearrange into ice, they release energy, or heat. "All this latent heat is not helping to nucleate ice," he says. Somehow — and the researchers don't yet understand exactly how it works — the bacteria are able to shuttle away the heat. The bacteria likely has to be alive for this part of the process. Figuring out exactly how it sheds heat could suggest other technological improvements, like better artificial snow.

So far, says Weidner, a snowboarder, the oldest use for ice-nucleating bacteria is his favorite. "Snowmaking would be the most fun application," he says.

Zach St. George writes about science and the environment. He's written for Nautilus, Outside Online, Bloomberg Businessweek, and others.

[Link]

Panspermia (from Greek πᾶν (pan), meaning "all", and σπέρμα (sperma), meaning "seed") is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by meteoroids, asteroids, comets,[1][2] planetoids,[3] and, also, by spacecraft in the form of unintended contamination by microorganisms.[4][5]

Panspermia is a hypothesis proposing that microscopic life forms that can survive the effects of space, such as extremophiles, become trapped in debris that is ejected into space after collisions between planets and small Solar System bodies that harbor life. Some organisms may travel dormant for an extended amount of time before colliding randomly with other planets or intermingling with protoplanetary disks. If met with ideal conditions on a new planet's surfaces, the organisms become active and the process of evolution begins. Panspermia is not meant to address how life began, just the method that may cause its distribution in the Universe

One could argue this is a is a form of another hypothesis Terraforming

[Link]

Terraforming (literally, "Earth-shaping") of a planet, moon, or other body is the hypothetical process of deliberately modifying its atmosphere, temperature, surface topography or ecology to be similar to the environment of Earth to make it habitable by Earth-like life.

The concept of terraforming developed from both science fiction and actual science. The term was coined by Jack Williamson in a science-fiction story (Collision Orbit) published during 1942 in Astounding Science Fiction,[1] but the concept may pre-date this work.

Based on experiences with Earth, the environment of a planet can be altered deliberately; however, the feasibility of creating an unconstrained planetary environment that mimics Earth on another planet has yet to be verified. Mars is usually considered to be the most likely candidate for terraforming. Much study has been done concerning the possibility of heating the planet and altering its atmosphere, and NASA has even hosted debates on the subject. Several potential methods of altering the climate of Mars may fall within humanity's technological capabilities, but at present the economic resources required to do so are far beyond that which any government or society is willing to allocate to it. The long timescales and practicality of terraforming are the subject of debate. Other unanswered questions relate to the ethics, logistics, economics, politics, and methodology of altering the environment of an extraterrestrial world

Given the proclivity of certain types to alter the very nature of our world this does not seem to be beyond the realms of possibility OSIT.