The boy pharaoh has been puzzling scientists ever since his mummy and treasure-packed tomb were discovered exactly 91 years ago on Nov. 22, 1922 in the Valley of the Kings by British archaeologist Howard Carter.

Only a few facts about his life are known. Tut.ankh.Amun, "the living image of Amun," ascended the throne in 1333 B.C., at the age of nine, and reigned until his death at between 17 and 19 years. He was a pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, probably the greatest of the Egyptian royal families.

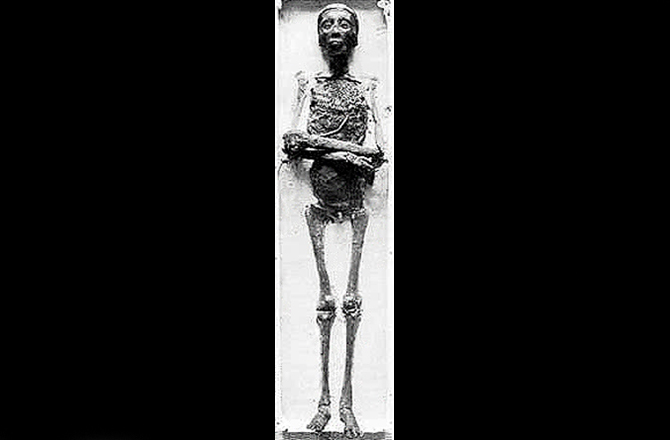

In 1925, three years after its discovery, King Tut's mummy was unwrapped in the outer corridor of the tomb of Seti II (KV15) by Carter and others.

That first examination provided intriguing details. The mummy was prepared in a way that was unlike that of any other 18th Dynasty royal mummy studied so far.

The different embalming procedure included a huge amount of resinous material poured over the body, and a penis fixed in an upright position.

The boy king's sexual organ was propped up with the help of resins, and possibly wrappings. It is not known why the embalmers mummified King Tut with an erect penis.

In fact, his genitals have presented another puzzle to archaeologists.

Photographed after unwrapping by Harry Burton (1879-1940), the royal penis was reported missing in 1968, when UK scientist Professor Ronald Harrison took a series of X-rays of the mummy.

Speculation that the penis had been stolen and sold abounded, but in 2006 Dr. Zahi Hawass, former chief of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, announced that the mummified genitals were re-discovered, buried in the sand surrounding the 3,300-year-old mummy.

But according to a recently published study, this is one of the many medical claims for which not enough evidence can be found.

Dozens of diagnoses have been proposed since the mummy was first unwrapped by Carter in 1925, ranging from infectious diseases, metabolic disorders, tumorous conditions, trauma and even murder.

"Through CT scans we found he had an accident two hours before he died. I really believe this accident could be a chariot accident," Dr. Zahi Hawass, the author of the recently published book "Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA," told Discovery News.

According to Frank Rühli, Head of the Centre for Evolutionary Medicine at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo, who authored the study, even with the best medical and forensic work, it is doubtful that all aspects of Tutankhamun's health and possible causes for his death will ever be known.

"It is just possible he died of the flu," Ikram said.

The abundant use of resin indicates that mummification for Tutankhamun was not standard.

"At least two separate lots of resin were used in the cranium. Possibly he was given a cursory mummification initially, perhaps because he died away from a center, and then he had a secondary, more mummification," Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo, said.

"If the initial work was substandard, a vast amount of resin would have been used to preserve his remains, which however seared away his flesh," she added.

Because of the abundant use of resin, the mummy suffered some serious damage: it was dramatically disarticulated in the attempt to remove jewels and amulets when Carter and others unwrapped it.

King Tut's mummy was wrapped in custom-made bandages similar to modern first aid gauze. Running in length from 4.70 meters to 39 cm (15.4 feet to 15.3 inches), the narrow bandages consist of 50 linen pieces with finished edges on each side.

On permanent display at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, the bandages are the leftover wrappings from King Tut's funeral. Similar pieces were probably were used to affix the larger sheets around the body.

The discarded embalming material was recovered from a pit (subsequently called KV 54) in the Valley of the Kings between 1907-08, more than a decade before Howard Carter discovered King Tut's tomb.

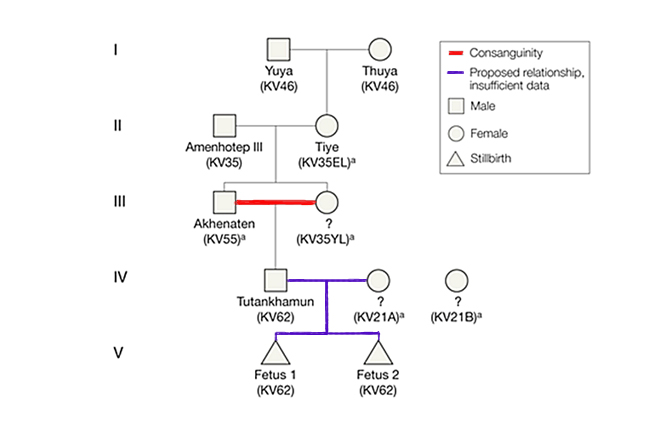

According to a major DNA study released in 2010, which involved 10 mummies closely related in some way to King Tut, a high degree of inbreeding characterized the boy king's family.

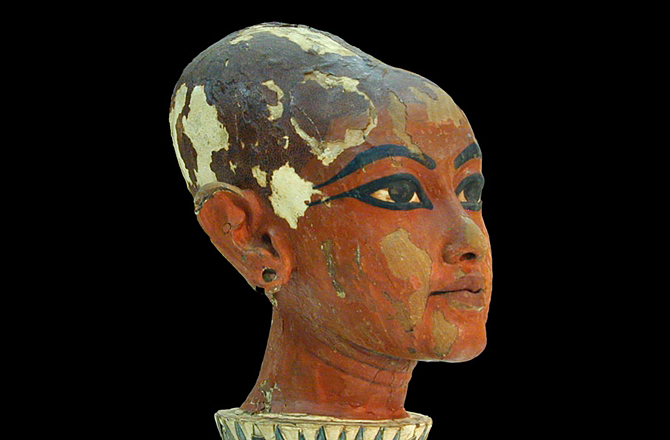

Producing the most reliable five-generation pedigree of Tutankhamun's immediate lineage, the study, led by Dr. Zahi Hawass, the former head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, revealed that King Tut was most likely the child of the "heretic" pharaoh Akhenaten.

Yuya and Thuya were recognized as his great-grandparents, while Amenhotep III and the mummy known as the Elder Lady (KV35EL) were found to be his grandparents. The mummy known as KV55 -- most likely Akhenaten -- and KV35YL, the Younger Lady, were identified as siblings, as well as King Tut's parents.

"This means Akhenaten married his own sister. We also know that the Younger Lady, King Tut's mother, can't be Nefertiti at all," Hawass told Discovery News.

Tutankhamun's inbreeding history continued as the boy was crowned king. The boy pharaoh married his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun.

King Tut fathered two daughters, both stillborn. Analysis of the fetuses, found in the pharaoh's tomb by Carter, revealed that one daughter died at 5-6 months of pregnancy and the other at 9 months of pregnancy.

DNA analysis revealed the mother of the two stillborn girls was resting in a tomb known as KV21.

"The tomb contained two female mummies, one of them headless. We found with DNA that the mummy with the head is most likely Ankhesenamun. I believe the headless mummy could be Nefertiti," Hawass told Discovery News.

King Tut wore a necklace with an "extraterrestrial" amulet at its center.

Found by Howard Carter in a chest near Tut's mummy, the pectoral, or necklace, features an amulet which is not "greenish-yellow chalcedony," as Carter had noted, but Libyan desert silica glass.

This is a natural glass that exists only in the remote and inhospitable Great Sand Sea of Egypt -- the Western Desert. In order to acquire the amulet at the center of the pectoral, the ancient Egyptians would have had to trek across 500 desert miles.

The true nature of the stone's material was discovered in 1999 by Italian researchers Giancarlo Negro and Vincenzo De Michele. The glass was produced by the impact on the sand of a meteorite or comet.

Symbolizing the voyage of the sun and moon through the sky, the elaborate motif of the necklace poses the question -- did the ancient Egyptians guess the celestial origins of the desert glass?

Reader Comments

I never noticed that before.

Egyptians