© Illustration by Frank Cecala/The Star-Ledger

Everyone knows the story of the Jersey Devil. In 1735, a witch named Mother Leeds gave birth to a hideous "child" with a horse-like head, cloven hooves, a long tail and bat-like wings. It yelped menacingly at the ragged, dull-witted family, then flew up and out the chimney to spend eternity harassing anyone who encountered it along the lonely back roads of the Pine Barrens.

Unfortunately, everything you think you know about the Jersey Devil is wrong. It is not a monster of the woods, but of politics. It is not a devilish horse haunting our present, but a scapegoat lost to our memory.

The Leeds family does occupy the center of the story, but they were not stereotyped, superstitious rural people. They were politically active religious pioneers, authors and publishers. We have forgotten that the Jersey Devil legend - originally the Leeds Devil - began as a cruel taunt against them, not because of a monstrous birth, but because they had the cultural misfortune of joining the wrong side.

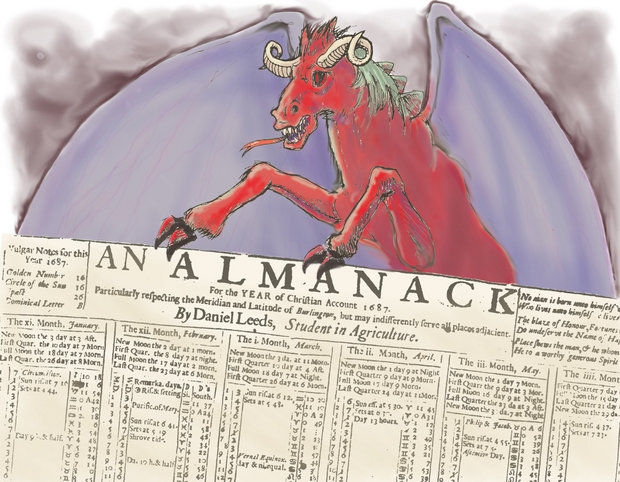

Daniel Leeds came to America in 1677 and settled in Burlington. He published an almanac and was promptly attacked by his Quaker neighbors over his use of astrology in it. Undeterred, he continued and, despite himself being a Quaker, they called him "evil."

Disillusioned by his treatment, he satirized the Quakers in a series of books. His work constitutes the earliest printing in the Garden State and some of the earliest political attack literature in America. His accusations of Quaker misdeeds so outraged them that they also called Leeds "Satan's Harbinger." To make matters worse, Leeds supported the first royal governor of New Jersey, the infamous Lord Cornbury, a man accused of being loose with the colony's taxes and a cross-dresser (both, we now know, slanders by anti-government pundits).

Eventually, Daniel's son, Titan Leeds, took over running the almanac and ran squarely into Benjamin Franklin.

The upstart Franklin was angling to make a name for himself as a publisher. As a publicity stunt, Franklin - in the guise of "Poor Richard" Saunders - claimed that astrological calculations showed Titan Leeds would die in 1733. When the prediction didn't pan out, Leeds called Franklin a fool and a liar. Never missing a beat, Franklin claimed that, since Titan Leeds had died, his ghost must be doing all the shouting. Leeds tried to defend himself, but Franklin kept a straight face and argued that Leeds had been resurrected from the dead. The plan worked. Poor Richard's Almanac became famous while the pioneering Leeds Almanac dwindled. Titan Leeds actually died in 1738.

As revolutionary fervor grew in the mid-18th century and Americans looked for targets to exercise their anti-British feelings, the Leeds family made easy marks. They had sided with the empire and the hated Lord Cornbury and had been charged with somehow being involved in the occult. By the time of the Revolutionary War, the "Leeds Devil" stood as a symbol of political ridicule and scorn.

Post-Revolution, the legend of the Leeds Devil drifted into obscurity until the early 20th century, when a Philadelphia public relations man revived it to promote a dime museum. The Leeds Devil became the Jersey Devil and fictitious monstrous births and bumps in the pine forest night eclipsed reality. A complex political animal had been transformed into a cartoonish, pedestrian and childish monster that never existed.

Today, you need not go to the Pine Barrens to hear the call of the Jersey Devil. You can hear it while watching misleading attack ads about which side is doing more, who the greater patriot is, or which politician is really an evil fascist. The Jersey Devil whispers to us a warning, not about the horrors of darkened forests, but of darkened hearts. It warns against false accusations, the demonizing of political opponents or individuals because of their look or lifestyle, of scapegoating, and about the tragedy of lost memories.

Brian Regal is a fellow of the Kean University Center for History, Politics & Policy and is working on a book about the Jersey Devil with Kean colleague Frank J. Esposito.

Reader Comments