© Co.Exist

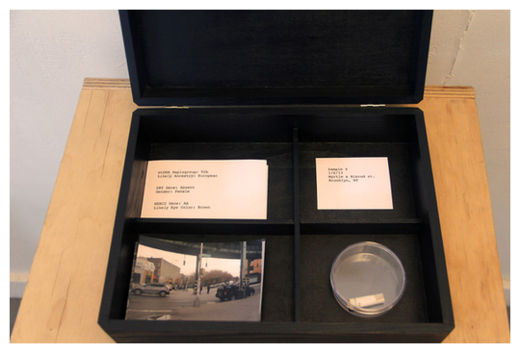

Stranger Visions is an art project which tries to determine what we look like based on a single strand of hair.

How much information about ourselves do we leave behind in public, as we shed saliva, hair, and sweat throughout the day? It's a question that drives the artwork of

Heather Dewey-Hagborg, whose project

Stranger Visions reconstructs the faces of the anonymous as 3-D printed sculptures, using genetic detritus found in chewing gum, cigarette butts, and wads of hair around New York City.

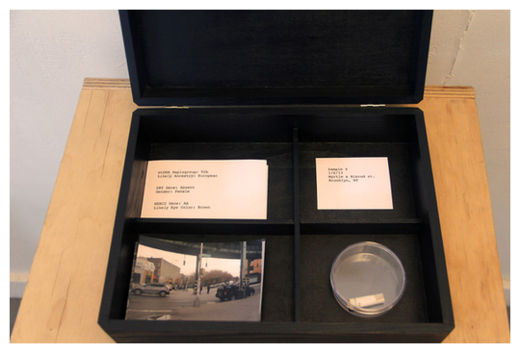

"I started fixating on this idea of hair and what can I know about someone from a hair," explains Dewey-Hagborg, a Brooklyn-based information artist. Her faces were determined based on looking at just three traits--gender, eye color, and maternal ethnicity--an admittedly simplified look (but still more advanced than police forensics labs which use a kit to determine hair and eye color from a sample). Plugging that information into software she wrote herself, she could spin up different 3-D versions of a face--eventually settling on the ones she finds most interesting aesthetically--and bring them to life with a 3-D printer.

The resulting busts may bear, at most, a "family resemblance" to the original person, Dewey-Hagborg says. "Part of that is that I need to do more experiments," to incorporate more traits. "Part of that is that it's just impossible."

© Co.Exist

While DNA analysis may be popularly understood as a straightforward process, thanks to simplistic representations on forensic lab TV mysteries where a single hair is as compelling evidence as a smoking gun, Dewey-Hagborg soon found out that "there's a whole lot more subjectivity than we're kind of lead to believe." Even something as simple as determining eye color based on DNA can prove harder than you'd imagine. "There's an 80% chance that this person has brown eyes and 20% chance that they have green eyes," she explains. "You have to make that call."

Subjectivity doesn't enter into the equation just at the level of DNA analysis but during machine learning as well. "In order to generate a face, you need to teach a computer what a face is," Dewey-Hagborg explains. But how do you tell a computer what something as complicated as a human's gender or race looks like? By feeding it images of humans with those characteristics, a process which involves human input-- the encoding of cultural biases and the simplification of complexity. Databases of faces often come from "college students in some particular region in the world," says Dewey-Hagborg, which clearly could skew toward a less diverse-swath of humanity. But in Dewey-Hagborg's software, the only way to determine what mouths and lips look like is based on ethnic prototypes linked to maternal ancestry.

Dewey-Hagborg calls the process "problematic," and she says she hopes her work provokes more of a discussion around subjectivity in both DNA analysis and computer modeling of faces. "It does involve, essentially, creating a stereotype, and generating faces based on those stereotyped ideas, so that's something I'm hoping to question with this work."

Soon, she hopes to expand the project to include more traits, including freckling and predisposition to obesity.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter