Men and boys constantly harass and threaten Al Momtaz on the bus, on the street and at the university.

"Every day men talk to me in a bad way, laugh at me and say things about what I am wearing," she told NBC News. On a recent bus trip, a man stuck his hand through a gap in the seat to touch her.

Al Momtaz has gotten off relatively lightly.

On Nov 25, Al-Ahram state newspaper reported three women were sexually assaulted during anti-Morsi demonstrations by hundreds of men.

In September, Eman Mostafa, 16, was gunned down after she spit in the face of a man who harassed her in the province of Assiut, according to police reports.

The Feb. 11, 2011, attack on CBS News' Lara Logan as she filed a report for 60 Minutes in Tahrir Square, epicenter of the uprising that forced dictator Hosni Mubarak to step down last year, brought international attention to the problem of sex attacks on women in public places.

Public violence against women was rampant well before the movement that unseated Mubarak in 2011. According to a 2008 study by an Egyptian NGO, 83 percent of women have been victims of harassment.

In the post-Mubarak era, activists and protesters have reported many particularly violent assaults on women. Some experts allege the government and security officials are failing to take the problem seriously. More than 700 claims of harassment were filed across Egypt over the four-day Id al-Adha holiday in late October.

"It is not a country of law, not a state of law anymore. It has given men a chance to harass women without being accused," said Afaf Marie, director of the Egyptian Association for Community Participation and Enhancement, an NGO.

Some activists fear that women's rights will suffer under the rule of President Mohammed Morsi, who is an Islamist.

Government inaction has allowed the problem to spiral out of control, Heba Morayef, director of Human Rights Watch for the Middle East and North Africa, told NBC News. Police no longer inspire fear as they did before the revolution. In addition, locals say it appears there are fewer police on the increasingly lawless streets -- and often none in Tahrir Square.

"The state is failing to respond," she said. "Men don't have to worry about being caught."

In addition, filing charges against an attacker is a daunting process in a society where sex is taboo, and police often don't take allegations seriously, Morayef said.

"Failure to prosecute is a major factor in the escalation of violence against women in public places," Morayef said.

Friend or foe

On Nov. 19, journalist Sonia Dridi was wrapping up her live report for French Channel 24 from Cairo's iconic Tahrir Square when a crowd of up to 30 men surrounded her.

In addition, filing charges against an attacker is a daunting process in a society where sex is taboo, and police often don't take allegations seriously, Morayef said.

"Failure to prosecute is a major factor in the escalation of violence against women in public places," Morayef said.

The mob pounded on the glass doors after she reached the safety of a Hardee's restaurant on Tahrir Square, which has become a sort of refuge for women. Dridi realized her skirt was unzipped and broke down in tears.

"The thing that was so sad was that the Hardee's waiters were ... waiting to help me because they are so used to that," she told NBC News.

Despite the risks, some women are venturing into potentially dangerous situations to stand up for what they believe in.

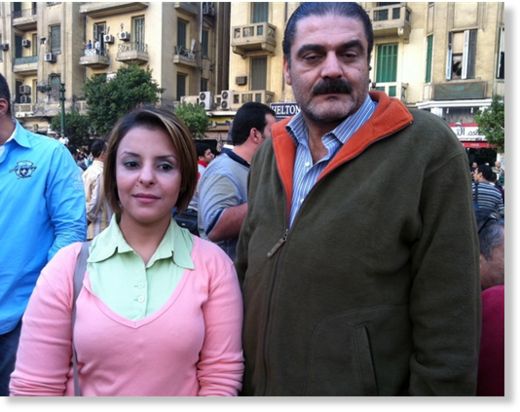

"I am afraid of harassment," said Mai Alam, 53, who was in Tahrir Square protesting against a recent Morsi decree giving himself sweeping powers. "I am with my husband and I keep pepper spray in my purse at all times."

"But this issue is more important than my fear of sexual harassment," the Egypt TV employee added.

And while women find ways of coping with violence, activists have formed groups to protect them. They say the police often don't intervene when women are attacked.

During a recent holiday, citizen vigilante groups patrolled Cairo during the recent Id al-Adha holiday, The New York Times reported.

At a recent march, men wearing fluorescent vests stood on rickety wooden towers and used binoculars to scan the crowd for signs of sexual mobbing. Local group Fouada Watch has set up a hotline for women, anti-harassment patrols seek to protect women in hot spots and bring alleged offenders to the police, and online services like Harassmap pinpoint dangerous sites.

Prime Minister Hisham Qandil recently announced that a law was being drafted to combat sexual harassment through harsh penalties, calling the issue a "disastrous phenomenon."

As the government decides what, if anything, to do about the epidemic of violence, women like Al Momtaz continue to try and carve out a normal life in a country that has empowered the bad along with the good.

"Everybody thinks that democracy and freedom are a license to do whatever they want," she said.

NBC News' Taha Belal contributed to this report.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter