Today's 6-2 ruling takes works by Alfred Hitchcock, Pablo Picasso, Igor Stravinsky and J.R.R. Tolkien out of the public domain, barring use without permission of the copyright owner. The decision is a victory for the film and music industries and a setback for Google, which had said it would lose access to many of the 15 million books it wants to make available online.

The justices rejected arguments from orchestra conductors, educators, performers, film archivists and movie distributors. They argued that the 1994 law violates the constitutional provision that lets Congress set up a copyright system, as well as the Constitution's free-speech guarantee.

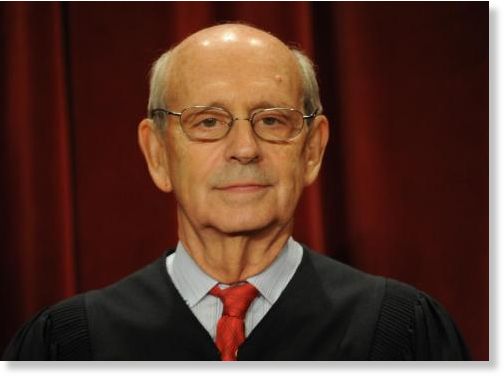

The law "lies well within the ken of the political branches," Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote for the majority. Justices Stephen Breyer and Samuel Alito dissented, and Justice Elena Kagan didn't take part in the case.

The statute aimed to harmonize U.S. copyright law with rules in other countries. The measure applied to works that had been excluded from the American copyright system for various reasons, in some cases because the U.S. didn't have copyright relations with the author's home country and in other cases because the U.S. hadn't yet recognized copyrights on sound recordings.

Picasso and Stravinsky

The law gave rights-holders the copyright protection they otherwise would have had. Affected works include Tolkien's The Hobbit, hundreds of Picasso paintings, several Hitchcock films and the music of Stravinsky, Dmitri Shostakovich and other Russian composers.

Congress approved the law to meet obligations stemming from the so-called Uruguay Round of international trade talks. The motion-picture and music industries pushed for the provision to secure reciprocal copyright protection for American works abroad.

"Congress determined that U.S. interests were best served by our full participation in the dominant system of international copyright protection," Ginsburg wrote.

The Obama administration defended the law, arguing that Congress has the constitutional power to remove works from the public domain.

No New Works

In dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer said the law went beyond Congress's constitutional power to confer copyrights for the purpose of promoting science and knowledge.

The law "does not encourage anyone to produce a single new work," Breyer wrote. "By definition, it bestows monetary rewards only on owners of old works -- works that have already been created and already are in the American public domain."

Breyer said that copyright owners often would be difficult or impossible to track down, particularly in cases involving older and more obscure works that have minimal commercial value.

"How is a university, a film collector, a musician, a database compiler or a scholar now to obtain permission to use any such lesser known foreign work previously in the American public domain?" he wrote.

Even if would-be users can track down the copyright owners, they may face other obstacles, said Anthony Falzone, the lawyer who represented the challengers to the law.

"It's not always just a matter of writing a check," Falzone said. "Copyright owners can say, 'No, we don't want you to do that. Forget about price -- we don't want you to do it.'"

A Google spokesman, Jim Prosser, didn't immediately return a phone call seeking comment. In court papers, Google said the law might affect as many as a million books the company has already scanned as part of its book project.

The case is Golan v. Holder, 10-545.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter