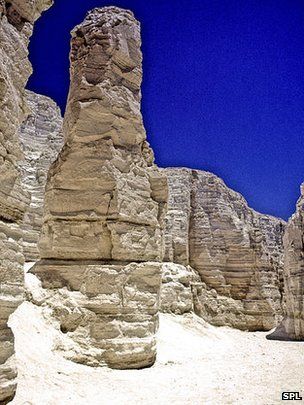

© SPLAragonite and gypsum deposits at the edge of the Dead Sea record the region's climate history

It is a discovery of high concern say scientists because it demonstrates just how dry the Middle East can become during Earth's warm phases.

In such ancient times, few if any humans were living around the Dead Sea.

Today, its feed waters are intercepted by large populations and the lake level is declining rapidly.

"The reason the Dead Sea is going down is because virtually all of the fresh water flowing into it is being taken by the countries around it," said Steve Goldstein, a geochemist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, US.

"But we now know that in a previous warm period, the water that people are using today and are relying upon stopped flowing all by itself. That has important implications for people today because global climate models are predicting that this region in particular is going to become more arid in the future," he told BBC News.

Prof Goldstein has been presenting the results of the drilling work here at the 2011 American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the largest annual gathering of Earth scientists.

© BBC

The Dead Sea is an extraordinary place. The surface of the inland waterway sits at the lowest land point on the planet, more than 400m below sea level.

Its hyper-salty waters descend in places a further 300m. And below the lake bed is layer upon layer of sediments that record the Dead Sea's history and the climate conditions that have prevailed in the region over hundreds of thousands of years.

A consortium of investigators from Israel, the US, Germany, Japan, Switzerland and Norway drilled two cores into the Dead Sea's bed in late 2010. One of them was centred close to the very deepest part of the lake.

At 235m down, the consortium hit a layer of small, rounded pebbles - what the team believes are the deposits of an ancient beach. Given the location of the core, this would suggest the Dead Sea had a complete, or near, dry-down at some point in the past.

Formal dating of the core sediments has not yet been completed, but their pattern leads the team to conclude that the dry-down occurred in the Eemian.

This was a stage in Earth history when global temperatures were as warm, if not slightly warmer, than they are today.

The modern day Middle East is preventing water getting into the Dead Sea. The surrounding countries are using it for agriculture. Fertiliser and salt manufacturing are also having an impact. Since 1997, the lake's surface has fallen more than 10m.

"Lake dry-down happened 120,000 years ago without any human intervention," said Prof Emi Ito, from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. "We're helping the lake level go down much sooner; and there are political implications of this lake drying down because water is what causes a lot of wars and I'll just leave it at that."

Prof Zvi Ben-Avraham, of the Minerva Dead Sea Research Centre, Tel Aviv University, added: "The drilling actually... it gives us perspective. Look what went on in 200,000 years; look how the area can be dry and look at the way it can be recovered. We have to get ready for the future."

Past research has shown very clearly how the size of the Dead Sea has fluctuated with the coming and going of ice ages.

© LDEOThe core contains rounded pebbles that the team interprets as an ancient beach deposit

During the interglacials (warm periods), the lake shrank; and during glacials (cold phases), the lake grew. And it was in the midst of the last ice age some 25,000 years ago that the Dead Sea reached its maximum extent, with the then water surface standing an astonishing 260m above where it is today.

This giant palaeo-lake, referred to by scientists as Lake Lisan, would have inundated the whole Dead Sea valley, even encompassing the Sea of Galilee to the north.

The consortium has traced these changes in the laminated sediments that line the surrounding cliffs and hills.

It is possible to see exquisite, alternating bands of light (aragonite) and dark (marl) material in the exposed rock.

The light layers are calcium carbonate precipitated out of the water in warm summer months. The dark bands are winter silts washed into the Dead Sea by storms.

But it is also possible to find layers of calcium sulphate (gypsum) and even salt, which relate to extended periods of dry weather when feed waters to the Dead Sea have not kept pace with evaporation.

"All these deposits from the last ice age are sitting at the edge of the lake, and we've been studying them for 20 years," said Prof Goldstein.

"They're beautifully exposed, but... as soon as we have a warm age, like we have today and like we had before the last ice age, the lake is lower and we have no exposures we can use. The only way we can get to those time periods is to have a deep drill core," he told BBC News.

© Agence France-PresseThe surface of the Dead Sea is falling by about a metre a year

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter