Lucy, 44, a writer, was about to step onto a sexual merry-go-round where casual adultery was the norm.

Here Lucy, who now lives with her English second husband and four children, tells Tessa Cunningham why the French are so different from us.

The first time I realised just how differently the French view sex was at my wedding. I married Laurent Lemoine at his parents' beautiful house in Normandy. Set in acres of lush farmland, it was the perfect bucolic setting.

As I walked down the aisle of the local church, I had never felt happier or more confident - until I caught sight of the guests. Dotted about the church were my husband's ex-girlfriends. Elegant, exquisitely dressed and immaculately groomed, they radiated a mixture of hauteur and sexual confidence.

I counted four of them. I'd been vaguely aware that these women were going to be at my wedding. Omitting them from the guest list would have been unthinkable. After all, most of them had been friends of my husband's since his school days and, until I came on the scene, some had been drifting in and out of his bed for years.

But seeing this congregation of his former lovers hammered home the gulf between our two cultures. I didn't know it at the time, but I was stepping into a world where educated middle-class - and married - people hopped into bed with one another free of guilt and free of consequences.

Those Parisian women, who would become my friends, didn't simply tolerate their husbands having affairs. They actually expected them to. Why not, when they were enjoying illicit sex themselves? And once it's no longer fun, you move on and there are no hard feelings. Everyone carries on being friends, just as my husband did with the women in that church.

I met Laurent when I was 18. I'd had a sheltered middle-class upbringing in London, where my father was a PR consultant and my mother a housewife. Home was in Chelsea.

It was 1983. I had a place to study English at Magdalen College, Oxford. My oldest sister (I'm one of five children) was living in Paris. Two of my friends were setting off on a trip around Europe and, on the spur of the moment, I decided to go with them as far as Paris.

However, when I arrived, my sister was out. Instead her flatmate, Laurent, answered the phone and offered to pick me up. When this handsome man, completely devoid of the self-doubt I had come to expect from English boys, rolled up outside the station, I was smitten.

For the next week, he pursued me with a persistence I found utterly captivating. Two weeks later, I was meeting his mother.

I had never known anything like it. I'd had several boyfriends, but what struck me about Laurent was that he was a grown-up. Not simply because he was 11 years older than me, but because he was utterly at ease with himself. Cultured, as only the French can be, and with a career in management consultancy, he exuded an intellectual self-confidence.

More significantly, he exuded sexual self-confidence. In England, I'd always felt I had to make the first move. If I didn't kiss a boy, I felt nothing would happen. It was as though they were terrified of putting a foot wrong and being too macho. As though the feminist movement had put them on their guard with women for ever.

Laurent had no such qualms. It was obvious, from the start, that in our sex life he would lead. I found that compelling. It made me feel desired.

He took me to Positano in Italy and proposed over a plate of spaghetti vongole. When I told him I was too young, he wasn't put off. He simply carried on his pursuit when I returned to Oxford.

And he did it with typical French panache. He knew the way to win me would be to play hard to get. So he gave me my first taste of those very French rules of seduction. It was like an equation: to prolong the pleasure, you prolong the hunt. And to invite desire, you make yourself scarce.

So he wouldn't ring for days, leaving me wretched with worry. Then he would turn up at dawn under my window, proclaiming his love.

I soon gave in. We married in July 1985. My parents were thrilled. They both adored Laurent and thought it was a wonderful match. His mother, Madeleine, came from an aristocratic family and his father, Jerome, an architect, was from the Parisian bourgeoisie.

But our apparent similarities masked a totally different attitude to the most integral part of marriage: sex.

The wedding was unsettling enough with the eyes of all those other women boring into my back at the altar. But it was nothing compared with what I was about to experience.

As Laurent's wife, I moved in a charmed circle. Our social life revolved around his wide group of gifted and beautiful friends, most of whom he had known since school, and many of whom he had slept with.

We'd been married two years and had our first child, Jack, when we went to a dinner party being held by one of Laurent's former girlfriends, Aurelie. I'd always been wary of her - Laurent had cheerfully told me she was a brilliant lover. He hadn't meant to hurt me. It was another example of his very French openness about sex.

But the information left me feeling bruised and insecure. Heatwave, as I nicknamed her, opened the door that evening radiating sexual confidence, wearing a dress that made her perfect body look as if it had been wrapped in black bandages.

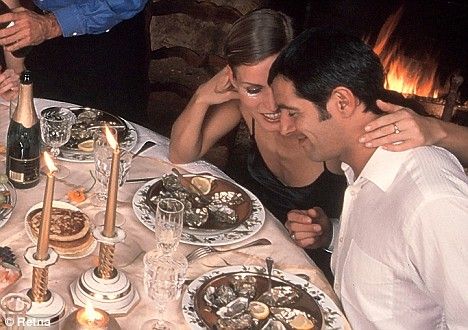

We sat at a long trestle table that ran down the middle of her garret flat and ate her magnificent food and sipped her carefully chosen wine. No one drank heavily. The guests, as I would soon realise, were anticipating more subtle pleasures. As the evening wore on, I noticed that a few men and women were peeling away from the table and moving into the next room.

As the Grand Prix was on, I assumed they were watching the highlights. Laurent was chatting to another male guest, so I wandered next door to see.

When I opened the door, the scene that met my eyes left me reeling with shock. A handful of men and women were arranged on a bed, some naked, some clothed. One of the women, locked in an embrace with a male architect and a female psychiatric nurse, looked up at me and inquired warmly if I would like to join them. I mumbled a polite 'no thank you' and fled the room.

I felt like a child stepping into a grown-up world. I dimly remember that a man emerged and came over to whisper in Laurent's ear. Laurent shook his head, as if he were declining a cigar. Then he looked across at me and gave me a cosy smile.

Even now, I don't know whether he'd been invited to join 'la partouze', as the French call these group trysts, but on the way home he made it clear that he was neither surprised nor shocked.

In fact, as I would soon discover, it was not unusual for the Parisian dinner party to end in this way. And although neither Laurent nor I ever joined in, I became used to it.

What was uniquely French about that evening was the spontaneity of it all. Nobody had to drink to oblivion, throw their keys on the table, or suggest a game of strip poker. Instead, this group of young, middle class couples had simply allowed the sexual charge to take over in a way that would be unthinkable in Britain.

It may be naive, but I don't think that Laurent was unfaithful to me, although if he had been, I would probably never have known because he would have been perfectly discreet. I never asked him. Bizarre as it might seem, it would have been rude.

I myself was propositioned several times. The first was after we had been married a few years. I was 24. One of Laurent's acquaintances, an auctioneer, asked me if I'd be interested in translating one of his catalogues.

He invited me out to an expensive restaurant off the Champs Elysee to discuss it. He was married, in his late 30s and not remotely attractive, and it never occurred to me to be suspicious.

But, in the middle of a short lecture on modern art, he asked: 'Would you like to be my mistress?' It was so ridiculous, I laughed out loud. 'I never joke about such matters,' he said coolly. 'Think about it. I know a lovely hotel where we could meet once a week. You would enjoy yourself and I would spoil you.'

'But I'm married,' I stammered. He looked at me as though I was utterly stupid. What difference did my marriage make? By the rules of this very sophisticated game, it had been vulgar of me to mention it.

Back home, I braced myself to tell Laurent what had happened. A British husband would have been outraged. But not Laurent. He was simply amused. 'He made a proposition and you declined. Where's the fuss?' he mused. 'I trust you and, besides, if you do ever decide to waver, I trust you to manage it so that it doesn't affect us.' I was stunned. How could he be so calm?

But then I thought of his parents' marriage and the 'special French women don't just tolerate their husbands' affairs - they expect them. We all know the French are, well, different. But nothing could have prepared a very middle-class English girl for the soulless sexual carousel of life as a Parisian wife arrangement' they had.

Every year Laurent's mother would spend six weeks in India and thus make room for her husband's mistress. One summer, we went to Normandy to find the house unusually clean. His mother was no domestic goddess, so I was surprised. Then one morning I went to the cupboard to get some marmalade for my toast.

There were rows and rows of freshly made jars. Each one bore the same label: 'Iris. Spring 1985.' When I questioned Laurent, he admitted the whole family knew about Iris. Everyone - even his mother - enjoyed her marmalade and never said a word about it. I only saw his mother Madeleine - a very intelligent woman - lose her temper once. It was when she returned from her annual holiday to discover that, while she was away, Jerome had taken their grandchildren out for tea with his mistress.

At first, I couldn't understand how my mother-in-law could tolerate this behaviour. But when I asked her why she didn't leave, she was horrified. 'We don't do divorce in this family,' she said firmly. And, over the years, I came to see her point. French couples - the educated middle classes at least - have no trouble accommodating affairs. In fact, they regard adultery as an occupational hazard.

They believe that everyone has a right to enjoy sex, with or without love. If you're lucky enough never to get bored with your partner, great. If not, there's no shame in looking for sex outside your marriage. It works in France because the French don't expect total honesty from their partners. In fact, they believe honesty can be downright destructive. In Laurent's circle, anyone who cheats on their partner would be regarded as cruel and petty for confessing to it. I suspect that, in a funny way, these discreet affairs help sustain marriages.

It can't be a coincidence that, while plenty of my English friends are divorcing, I know only one divorced couple in Laurent's circle - and the wife is American. Unlike the French, we have a very puritanical view about honesty. We see a relationship with secrets as a flawed one, and so any affair ends up mired in guilt and recrimination.

Often it's the guilt and deceit, not the sex itself, which destroys the marriage. Put bluntly, we regard affairs as sordid. The French see infidelity as natural. For many, good sex is the most satisfactory way to escape drudgery and stress.

The problem was that trying to live like this went against everything I'd been brought up to believe in. I adored Laurent and never for one moment doubted that he loved me. In so many ways he was the perfect husband. He bought me flowers, whisked me away for surprise weekends and made me feel cherished.

In short, he did everything he could to prolong the game of courtship. But, as the years passed, I yearned for the kind of intimacy that comes when a couple are striving for total honesty.

I longed for the transparency that I'd been raised to think was essential in a loving relationship. All the game-playing with my husband and his friends was alluring, but ultimately unsatisfactory.

With Laurent there was, from the beginning, a feeling of distance. Being slightly aloof and secretive was a large part of his appeal when we met. It was also part of his culture.

This behaviour makes affairs easy. And French women are conditioned to behave the same. I wasn't. I longed for Laurent to tell me how he felt. If ever I sensed that he was unhappy he would never open up, however much I probed.

In September 2000, when I was 35 and after 15 years of marriage, I fell in love with Joe, an English photographer. Suddenly, the gulf between Laurent and me was exposed. When I told him that I'd met someone else, he asked: 'Why can't you just have an affair?'

His suggestion seemed unthinkable. The man I'd met was what Laurent would call an 'Ayatollah of Truth'. He, like me, was looking for total honesty.

Laurent and I divorced in 2002 and Joe and I now live with our two sons in the Cevennes, about eight hours' drive from Paris.

Laurent and I are good friends and I don't regret our marriage for a second. He's enjoying the carefree life of a divorcé in Paris. My own life suits me much better. Joe, 40, and I live in each other's pockets. We have no secrets - and affairs are absolutely forbidden.

The Secret Life Of France by Lucy Wadham was published by Faber and Faber on July 2, £12.99.

While I'm certainly not advocating for the paradigm of sex being casually emotionless (or advocating for any other types of relationships over others, for that matter), Lucy seems to miss an important aspect of herself in her relationships that seems to be frequently missed in relationship interactions that I've observed, including my own.

"...he pursued me with a persistence I found utterly captivating"

and

"It was obvious, from the start, that in our sex life he would lead. I found that compelling. It made me feel desired. "

My observations have led me to believe that many individuals are seeking relationships not as a means of finding a deep, intimate, and supportive relationship with another individual, but as a means of providing evidence that they are desirable or 'good' in the judgment of others (especially in the emotionally sensitive realm of sexuality), possibly to counteract an ingrained belief from earlier in life (or from social programming of what's sexually attractive through media outlets). Particularly with Lucy's use of the word 'love' as the label for their relationship and in light of the following article (and careful observation of when people use the word 'love' and to what they're specifically referring to):

[Link]

Perhaps Lucy is really referring to something else when using the word 'love' in this context, or at least referring to multiple aspects of her relationship with Laurent.

This quote, I think, is particularly worthy of deconstruction:

"one of Laurent's former girlfriends, Aurelie. I'd always been wary of her - Laurent had cheerfully told me she was a brilliant lover...But the information left me feeling bruised and insecure. Heatwave, as I nicknamed her, opened the door that evening radiating sexual confidence, wearing a dress that made her perfect body look as if it had been wrapped in black bandages. "

Lucy takes the information that Aurelie was a very pleasurable lover, which implies a high level of desirability, as also implying that she (Lucy) is somehow less desirable or that Laurent may desire other people as well as her, which leaves her "feeling bruised and insecure". However, Laurent does not say this, nor does he seem to imply it from Lucy's description, which suggests that Lucy is the one who is creating this feeling inside herself about her. This seems to beg the question: does one's partner finding someone else attractive mean that one is subjectively 'bad' or even 'less good'?

Lucy goes on to nickname this person 'heatwave', which seems to reduce this person below the level of a human being who has lived a full life, like her, likely with her own hardships and challenges (how many women, especially since agriculture set in and especially ones who are deemed to be sexually attractive in the mainstream body image programming, would describe their lives as being without hardship? how many sexual assault survivors and rape survivors are out there today?). Perhaps lowering this person (not referring to her by her name) below the level of someone who's perhaps had similar life challenges provides the author with some power over the negative feelings she's experiencing from her own negative self-judgment from the data that Aurelie 'was a brilliant lover'.

Continuing on, Lucy seems to describe love as a feeling, and certainly it seems clear that she has experienced this feeling before in her life. Perhaps, however, 'love' is not the most accurate word for the feeling she's experiencing--perhaps it's something more along the lines of addictive gratification/validation and [ego] attachment (see articles):

[Link]

and

[Link]

Lucy also says in the article (on being pursued by Laurent as a 'distant lover'):

"So he wouldn't ring for days, leaving me wretched with worry. Then he would turn up at dawn under my window, proclaiming his love. "

She describes herself as feeling 'wretched with worry' after not hearing from her partner for 'days' (sounds like less than seven, otherwise it'd probably be described as 'weeks'), and then Laurent would 'proclaim his love' and, presumably, she would feel all better (she'd probably feel very desired, and attractive, even). To me, rather than 'love', I would describe this as addiction.

There are a host of chemicals that one experiences in a variety of the interactions that one has with another person with whom they are sexually involved, especially when that involvement passes whatever line exists wherein the two become 'partners' or 'boyfriend'/'girlfriend' or 'married'. The article ("Your Brain in Love") cites dopamine and norepinephrine, both of which are pleasurably addictive in the body, and can arise in many different phases of the relationship between two people ('love at first sight', sex, cuddling, kissing, shared sleeping, etc). Along with those two chemicals, cuddling and sex both lead to the release of Vasopressin and Oxytocin as well (though I'm unaware if either of those has been identified as being addictive), both of which are relaxation hormones.

Perhaps another facet of the 'love' feeling that Lucy is describing has to do with having a source/support person to aide in the release of the relaxation hormones that one may [desperately] need in a stressful life (which may be especially stressful if Lucy is struggling to feel confident and valid as a living being amidst her partners former/other lovers). Perhaps there is another method one can use to satisfy one's needs for the relaxation hormones.

Lucy also talks about her current relationship as having no secrets (admittedly, not the same as being totally honest, which of course requires one to be totally honest with oneself) and that the French don't expect the same from their partners:

"It works in France because the French don't expect total honesty from their partners."

However, I wonder if Lucy is being totally honest about her inner emotional state and the feelings she's having, either with herself or her current partner, along with the sources of these emotions and whether or not she's addicted to them. She also seems to contradict herself in the regard that the French "don't expect total honesty from their partners", when she says (about Laurent's father's mistress):

"When I questioned Laurent, he admitted the whole family knew about Iris. Everyone - even his mother - enjoyed her marmalade and never said a word about it."

It seems, since everyone knew about it, that there was at least a minimal level of honesty, albeit perhaps, since no one talked about it, also a separate level of dishonesty. Perhaps Laurent's father's dishonesty would manifest in the form of not expressing how much this other person (mistress) means to him. Or perhaps he's not being honest with himself about how much he needs to have a sexual partner/relationship to feel 'good' about himself; I don't know.

Most addicts, it seems, find it very difficult to be honest about their addiction ('I can quite any time', 'I've got it under control', 'I don't have a problem', etc) and I imagine this comes from an emotional attachment to beliefs (especially the 'ego' beliefs--that one is judged positively [or negatively! very important too!] by others) and the emotional resistance to seeing beliefs be wrong or seeing oneself as being wrong. Being right, either 'good' or 'bad', is quite addicting in itself, but paints a distorted picture of the world, as taking in new information and being wrong is essential to life and learning.

Being open to being wrong provides a way, albeit a difficult one, out of the distorted picture that one paints for oneself in life, creating the picture of one in one's mind as one wants to be, rather than what one is. But looking honestly and objectively, taking in all evidence and not just what one wants to see or what supports a theory one has that one wishes is correct, is an incredibly challenging task. Perhaps, though, it's one of the greater forms of self love (not love for self) that are available at this time.

I'm certainly not saying that Lucy is a bad person, nor am I saying that casual sex is 'the way' (what is one getting from a sexual relationship without intimacy or support? Is it feeding something or masking something? Is it 'just fun', and if so, what does that mean?) or monogamous relationships are inherently ego-oriented, but my observations over time (and especially in myself) have led me to believe that many individuals are not being honest about what they're really getting and doing in a relationship (of any sort--not just sexual ones).

Regardless of anything else, sexual relationships certainly offer a great opportunity to observe oneself and gain a greater self-understanding, even if the relationship is just casual. But observation is not automatic and only comes about with effort. With effort, though, one may come to learn a great deal about oneself.