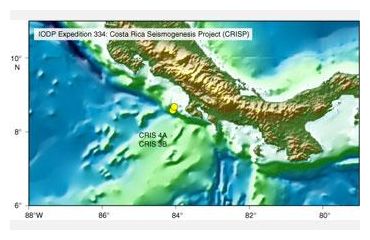

© IODPThe CRISP research site is located 108 miles (174 km) off Costa Rica.

Pieces of rock and seafloor from deep in the Pacific Ocean near Costa Rica may help explain why Japan's deadly magnitude 9.0 quake was so large.

Nearly one mile of sediment cores (cylinders of earth drilled out from the ground) collected from the

ocean floor off the coast of Costa Rica reveal detailed records of some two million years of tectonic activity along a nearby seismic plate boundary, where one tectonic plate dives beneath another, called a subduction zone. It was the rupture of a subduction zone that generated

the Japan temblor.The scientific drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution retrieved the samples during a recent monthlong expedition called the Costa Rica Seismogenesis Project (CRISP). Participating scientists aim to use the samples to better understand the processes that control the triggering of

large earthquakes at subduction zones.

More than 80 percent of global earthquakes above magnitude 8.0 occur along subduction zones.

"It's critical to understand how subduction zone earthquakes and tsunamis originate - especially in light of recent events in Japan," said Rodey Batiza of the National Science Foundation's Division of Ocean Sciences. "The results of this expedition will also help us learn more about our own such zone off the Pacific Northwest."

Factors at play"We know that there are different factors that contribute to seismic activity. These include rock type and composition, temperature differences and how water moves within the Earth's crust," said co-chief scientist Paola Vannucchi of the University of Florence in Italy, who led the expedition with co-chief scientist Kohtaro Ujiie of the University of Tsukuba in Japan.

"But what we don't fully understand is how these factors interact with one another and if one may be more important than another in leading up to different

magnitudes of earthquakes," Vannucchi added.

The expedition gave the scientists crucial samples for answering those fundamental questions, Vannucchi said.

During four weeks at sea, the scientists and crew successfully drilled four sites, recovering core samples of sand and claylike sediment and basalt rock.

The expedition is unique because it focuses on the properties of erosional convergent margins, where the overriding plate gets "consumed" by subduction processes. These plate boundaries are characterized by trenches with thin sediment covering less than 1,312 feet (400 meters), fast convergence between the plates at rates greater than 3 inches (8 centimeters) per year, and increased seismicity.

The recent Tohoku earthquake in Japan was generated in an erosive portion of a plate interface.

Plate interactionIn a preliminary report published this month, CRISP scientists say that they have found evidence for a strong subsidence, or sinking, near Costa Rica combined with a large volume of sediment discharged from the continent and accumulated in the last two million years.

"The sediment samples provide novel information on different parameters which may regulate the mechanical state of the plate interface at depth," Ujiie said. "Knowing how the plates interact at the fault marking their boundary is critical to interpreting the behavior and frequency of earthquakes in the region."

Vannucchi adds, "for example, we now know that fluids from deeper parts of the subduction zone system have percolated up through the layers of sediment."

"Studying the composition and volume of these fluids, as well as how they have moved through the sediment, helps us better understand the relationship between the chemical, thermal and mass transfer activity in the seafloor and the earthquake-generating, or seismogenic, region of the plate boundary," he said. "They may be correlated."

The seismically active CRISP research area is the only one of its kind that is accessible to research drilling.

However, this subduction zone is representative of 50 percent of global subduction zones, making scientific insights gleaned here relevant to Costa Ricans and others living in

earthquake-prone regions all around the Pacific Ocean, including Japan.

The CRISP team hopes to return to the same drill site in the future to directly sample the plate boundary and fault zone before and after seismic activity in the region. Changes observed may provide new insights into how earthquakes are generated.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter