Our packed prisons are starting to disgorge hundreds of mostly African-America men who, over the last few decades, we wrongly convicted of violent crimes. This is what it's like to spend nearly thirty years in prison for something you didn't do. This is what it's like to spend nearly thirty years as someone you aren't. And for Ray Towler, this is what it's like to be free.

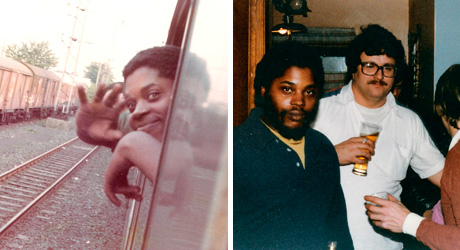

© Michael EdwardsRay Towler

A little girl sitting in a big chair, the witness stand in Courtroom 15-B, overlooking the lake in downtown Cleveland.

It is a Monday morning in September 1981. The girl is eleven. Her name is Brittany. She's in sixth grade, weighs eighty-nine pounds. She lives with her mom and her eighteen-year-old brother. Frequently she stays overnight at her aunt's house. Her cousin is named Jack. He is a year older, in the same grade at the same school. They spend a lot of time together.

Late in the afternoon on the Saturday of Memorial Day weekend, Brit* rode her bike unsupervised from her house to Jack's. The area where they live, the west side of Cleveland, is predominantly white. It is considered the safe part of town.

Upon waking the next morning - Sunday, May 24, 1981 - Brit and Jack got the idea to go on a picnic in the park, something they'd done many times before. They went to a local market and bought provisions, returned home to pack lunch. As they busied themselves in the kitchen, Brit mentioned this cool fallen log she and her girlfriend had found two weeks earlier; you could climb out onto the end and dangle your toes in the river. She really wanted to show it to Jack. He was psyched. Every good outing needs a mission. This would be theirs.

With Mom's permission, off they went the short distance, Brit on her ten-speed, Jack on his Huffy. Down Wagar Road to Detroit Avenue, into the entrance. The park was officially named the Rocky River Reservation, but everybody called it the Valley - one link in a chain of lush metro parks that followed the meandering Rocky River south from Lake Erie and on past the airport. There were massive shale cliffs, bountiful forests, nature trails; a marina, bridle paths, three golf courses.

It was hot and humid, just past noon. They entered at the Scenic Park Marina, headed south along the All Purpose Trail. The thirteen-mile path was shaded and nicely paved; there was the usual sparse but steady flow of joggers and bike riders.

At some point along the way, the kids stopped to eat. Afterward, they resumed their journey southward until they reached the first golf course - two miles as the crow flies from where they started but probably twice that far in actual distance given the serpentine trail. From there they returned north, looking for Brit's special log.

They dismounted their bikes and began walking, Jack on point, Brit following. A black man approached from out of the woods. He was wearing sunglasses and had a stubble of beard. He was carrying a rolled up article of clothing beneath one arm. Two eye witnesses - a young secretary on roller skates and a tool-and-die maker who volunteered info to the police after being stopped with an open beer - would later testify that he was the only black person either of them saw that day in the park.

"I found a deer and I think it has a broken leg," the black man told the kids. "Could you come and help me?"

Without hesitation, Jack said yes.

Brit wasn't so sure.

"Jack," she implored.

Jack didn't heed. There was a new adventure at hand. He set his bike against a tree and followed the man into the woods. Brit did the same.

A few hundred feet into the forest, the man turned and produced a gun from the rolled-up article of clothing - a wood-handled police-type revolver. Jack was shoved against a tree, ordered to kiss the dirt. Brit was dragged by one arm a few feet away from her cousin.

The man pulled down his pants, untied Brit's yellow jumper. He pulled down her underpants.

"And then what did he say?" the assistant prosecutor asks. His name is Allan Levenberg.

"He said, 'Lift your legs,'" Brit testifies.

"Did he do or say anything else at that time?"

"Yes."

"What was that?"

"He said, 'Is it in?' and I said, 'I think so.'"

A stunned, horrible silence falls upon the courtroom. Levenberg continues gingerly, speaking as much to the jury as to Brit, in the manner trial lawyers have. He makes sure the words penis, entered, and vagina are added to the public record.

Then he asks: "This black male you have been telling us about ... the one you followed into the woods to look for this phantom deer. Do you see him in the courtroom today?"

"He is over there," she says. She points a small finger. "He has a blue shirt on and blue pants."

Raymond Daniel Towler is sitting at the defense table. He is a big guy, twenty-four years old, with a full puffy beard and a quick smile; his burnished ebony skin is a shade darker than the rich wood paneling in the courtroom. By most accounts he is a gentle, talented, thoughtful man who studied art in community college. He earns a living working temp jobs and lending his Jimi Hendrix - inspired guitar stylings to various rock bands around town. At the time of his arrest, he was collecting unemployment, thinking about reenlisting in the Army. He was living with his mother and little sister in a modest house on the west side, three miles from the Valley, a place he's been going with relatives and friends his entire life.

Ray Towler does not claim to be the best man on the planet. He's really just a regular guy. Though he doesn't drink, he does enjoy the occasional doobie - it is 1981, after all, and he is a musician. He has yet to find a regular civilian job. You could say he's always been a little bit adrift - a black kid in a white school who wanted to be an engineer or an astronaut but who was counseled toward shop classes and the assembly line; a volunteer soldier who was told he could learn how to work on missiles but ended up in the infantry; a veteran with an honorable discharge who served overseas and then came back home to ... the same old shit he was trying to escape.

One thing he is absolutely sure of: He is no child molester.

No fucking way.

And yet, inexplicably, he is here.

On trial for rape, kidnapping, and felonious assault.

Facing a life sentence.

Which is really a death sentence - a long, slow, lingering death behind bars.

Sitting in the hard courtroom chair, Towler feels weirdly detached, like he's here but he's not. He studies the little girl and the judge and the prosecutor. He's trying to listen, he knows he should be listening so he can make some sense of what's going on, so he can try to figure out what the hell has happened, how this huge mistake got made. It's hard to concentrate. He thinks about all the stuff black folks have endured throughout history. He thinks about Dr. King and lynching parties and white hoods. It's like he's entered the Twilight Zone - the worst horror movie you could ever imagine. In court they keep talking about this man. They keep asking the witnesses, "Did he do this?" and "Did he do that?" Evil, perverted, unconscionable things.

And every time they say the words Did he, they mean him: Ray Towler.

He wonders about the little girl in the big chair, about the prosecutors, about God. Why are you doing this to me? He has never before in his life seen these children.

Why are you accusing me of something I didn't do? Are you covering up for someone else who hurt you? How could these people really think it was me to do something like this? Towler looks to his lawyer, an old white guy with mismatched socks. His name is Jerome Silver.

Every one of his objections has been overruled! During the girl's testimony, Silver is holding a pen poised above a legal pad. His hand is shaking.

Towler's head throbs. He wants to cry. He wants to throw up. His whole family is sitting behind him in the courtroom listening.

This is how it's going to be. For the rest of my life, I'm going to be thought of as a person who does this kind of stuff to little kids.

He feels like somebody is holding him down and beating him in the back of the head with a baseball bat.

*The names of Brittany and Jack have been changed to protect their privacy.

Ray Towler

Early the next morning, before the trial starts for the day, Towler and his lawyer are called into the judge's chambers for a meeting. The Honorable Roy F. McMahon is semiretired but still hearing cases. Levenberg, the assistant prosecutor, is also present.

The judge asks Towler if he'll take a plea bargain.

"Maybe I'd consider if you tell me what you're putting on the table," Towler says.

The judge addresses Towler's lawyer. "If you don't mind, Mr. Silver, I'm going to talk to Mr. Towler alone."

When Silver objects, he is once again overruled. From day one of the trial, it has seemed to Towler that the judge's attitude has been,

Okay, we already know how this is going to end, let's just get it over with.

Towler watches his lawyer's back recede.

Walkin' out the room with your tail between your legs, he thinks derisively. What kind of a lawyer can't even save an innocent man? At the time of the crime - approximately 1:00 P.M. on Sunday, May 24 - Ray Towler swears he was in his bedroom at home, coolin' it and listening to music after a late party at his mom's house the night before.

It had been the usual family gathering: Moms grilling, people bringing covered dishes, gin and juice. Towler went to bed early, around 1:00 A.M. The low-key festivities lasted until four - even the kids stayed up until the wee hours.

The next morning, the day of the rape, Towler's nine-year-old niece, Tiffany Settles, woke up at 7:30. His moms, Josephine Drake - for years a data programmer, the daughter of a registered nurse and a construction worker - rose to supervise and fix breakfast. Towler came downstairs at about 12:30 or 1:00 to use the only bathroom. His moms and Tiff were watching a Ma and Pa Kettle movie on Channel 61. His ten-year-old sister, Priscilla Drake, was still asleep.

Towler went back up to his room. It was a close house, probably no more than thirteen hundred square feet over two floors. For the next few hours, his radio and his footfalls could be heard, but he was not actually seen. At 3:00 or 3:30, Towler reemerged from his room, clomped down the steps, passed through the living room to get a drink of cold water from the fridge. Then he took a shower and went back upstairs to get dressed. In about an hour, with a summer downpour threatening, he would sweep out the garage so the girls could roller-skate in there without getting wet.

By that time, having concluded a rape exam at a local hospital, little Brit was being questioned by authorities, according to testimony at the trial.

Thirteen days after the rape, on the afternoon of June 6, Towler drove the three miles to the Valley in his green Monte Carlo, a clunker with the door and trunk locks punched out. He'd bought it recently for $700, the amount he'd gotten for selling his pro-quality reel-to-reel tape recorder.

Even though Towler went to the Valley occasionally, he never stayed down there very long. When he was little, his moms used to take him all the time - picnics, baseball, hide-and-seek. Later, as a teen, he would usually go in a group; the rangers always wanted to stop and hassle them. Cleveland might not be the South, but the history of race relations here is as tortured as anywhere in the nation. Suffice it to say that while Ray Towler felt an inalienable right to be in the Valley, he wasn't 100 percent comfortable whenever he was actually there.

As he was leaving the Valley, Towler was pulled over for rolling through a stop sign - which was weird because he was sure he hadn't rolled through no stop sign. He was a very careful driver. Especially when he was in the park, or anywhere else on the west side. Driving While Black. It didn't have a name back in 1981 - nobody really talked about it openly until Rodney King had his run-in with the Los Angeles police a decade later. But every black man in America knew the concept well.

The ranger issued Towler a ticket, but he seemed much more interested in bringing him back to the station house and taking his photograph... .

Which in turn would be selected from an array of eleven photos by the four witnesses: Brit, Jack, the skater girl, and the open-beer-can informant.

On June 19, police took Towler away from his mom's house. He's been in jail ever since.

Now it is September and the weather is changing. Towler is well into his trial. Judge McMahon is tall and skinny with a long face. He makes Towler think of a skeleton in a black robe. He's just asked Towler if he wants to make a deal. Towler has asked the terms.

Plead guilty, the judge tells him, according to Towler, and "we'll take care of you."

In the movies, when someone in power "takes care" of somebody else, it doesn't usually end very well for that person. Towler doesn't know what to say, so he says nothing.

The judge looks annoyed. "Do me a favor," he tells Towler. "Get up from that chair and stretch your legs a bit, check out the view from the windows."

From where they are situated, somewhere high up in the highest tower at the judicial-center complex, facing north, Ray can see the blue sky meeting the blue waters of Lake Erie, a seemingly infinite view. The shallowest of all the Great Lakes, carved by glaciers, the lake that drains and replenishes itself the most often ... how many times had they taught him those fun facts during his school years? In the foreground he can see a little airport. In the middle distance a few sailboats. Beyond that is Canada, he supposes.

"Get a good look at that view," Judge McMahon says. "If you don't take this deal, you'll never see that lake again."

Instead of making Towler feel defeated, the judge's remark makes him mad.

If they gonna railroad me, he tells himself, they gonna have to do it all the way.Towler takes the stand in his own defense. He swears he has never before seen the little girl or the little boy. He was at home during the time the crime was committed. What more can he say? He didn't do it.

His mom, his little sister, and his little niece confirm his alibi. His lawyer drives home the point that Towler - now, for a long time, and in the photo taken of him that day - has a full beard, not a stubble, as described by the victims. His argument that Towler did not own a pair of sunglasses is less convincing.

The trial lasts seven days - the first three consumed by motions, impaneling the jury, and a field trip down to the Valley and the scene of the crime; the last one and a half dedicated to impassioned summations, followed by a seemingly endless jury charge.

After one morning of deliberation, a verdict is returned.

Ray Towler is found guilty of rape, kidnapping, and felonious assault.

Judge McMahon sentences Towler to life for his crimes against Brit. For those against Jack, he receives an additional twelve to forty years. In addition, Towler is ordered to pay court costs of $1,951.95, due within sixty days, subject to interest charges thereafter.

Assistant Prosecutor Levenberg tells the press: "Anyone who preys on children should be put away and the key lost. This man, an animal, got what he deserved - life!"

© Mike EdwardsRay Towler

Towler is transferred from the county lockup at the Justice Center to orientation at the Ohio Penitentiary (broken windows, pigeons flying around the tiers) to the maximum-security facility at Lucasville (an inmate population composed mostly of lifers).

Attorney Silver handles the appeal.

Denied.

Ray becomes his own jailhouse lawyer, pro se. He asks the governor of Ohio for a commutation. He petitions the federal district court for a writ of habeas corpus. He applies to the sentencing judge for early release.

Denied. Denied. Denied.

After seven years, he is moved to lower-security facilities at the Marion Correctional Institution.

At the twelve-year mark, he sees the parole board in person.

Denied.

Two years later, he is moved to a minimum-security prison at Grafton, Ohio, and eight years after that he moves to the Grafton Farm. Most of the inmates at the farm are allowed to work outside. Some can even drive into town themselves. As a convicted child molester, Ray cannot leave the facility unsupervised. He has a similar problem with the mandatory courses he's supposed to take: Because he refuses to stand up in group and admit he is a child molester, he is not allowed to participate.

Years pass. He sees a couple guys have heart attacks. He sees a few guys get killed - they're lying there bleeding, you know, you just keep moving. He sees beat-downs, beefs, hassles, rapes. He watches a cellie die slowly of a heart blockage - a decent older man who'd shot a guy for messing with his daughter. Towler is locked down in solitary twice. The first, a ninety-day stint, follows a routine shakedown: His cellie has a shiv fashioned from a spoon he bullied Towler into bringing back from the kitchen. The second stint follows the death of his mother, in 1984. He is allowed to go to the funeral; he wears shackles. When he returns, he asks to be put in solitary - he just wants to be alone. Over the years, most of the prisons in which he is housed are far from home - one is on the border with Kentucky. After the funeral, the only relative who visits is his sister Deborah.

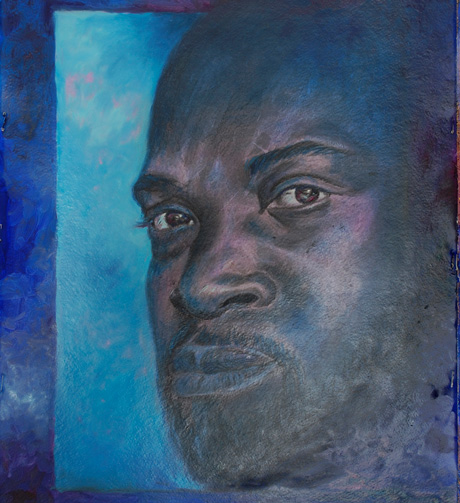

From the very beginning, he draws portraits of guys, amazingly realistic likenesses with a number-2 pencil, on the back of an envelope or on a sheet of plain paper, something very special an inmate can send to his mom, his woman, his kids. Ray sells the portraits for cash or other valuables. His talent grants him a certain respect within the prison community, despite the mark of his despicable crime, which is written at the very top of his file and all of his paperwork, along with his prison number, 164681. His offense follows him everywhere. There is no escape. He says he feels like the actor Chuck Connors on that old TV show Branded. The theme song plays over and over in his head:

What do you do when you're branded, and you know you're a man? That he is almost six feet tall and weighs three hundred pounds also helps keep him safe. His worst moment comes one afternoon at Lucasville when three would-be assailants corner him in the dish-washing area of the kitchen. Luckily he's been warned; only by mentioning some special words given to him by his cellie does he avoid becoming their bitch. (He still doesn't understand exactly what he was telling them. He thinks maybe he was saying he was already taken.)

He carries himself upright. He doesn't complain and moan. He doesn't gossip. He does his own time. He maintains his maintain. Never for one minute does he ever let himself think he is destined to spend the rest of his life behind bars - he knows he might, but he never thinks he will ... so he doesn't live like that, like an animal in a cage. He tries to live like he's at home. He tries to respect himself and others. He acts in a way that makes others respect him. His Zenlike demeanor, a calm he's possessed since childhood - when he used to sit for hours and draw on the data-entry cards his moms brought home for that purpose - fits well to his circumstances. He has the patience of an artist - to render a face with a million tiny strokes. At Lucasville he does wall murals in the cafeteria - using scavenged house paint and car paint and spray paint - in exchange for better food. By the time he gets to Grafton, he has the coveted job of overseeing the rec department. There is an art studio with a nice airbrush and plenty of supplies, four hours a day of uninterrupted time to paint. Each of his canvases takes a week to complete. Over the years, he makes more than four hundred large pieces, and many more small ones. The top price is $250. Even the assistant warden buys a portrait. With the earnings Ray buys a television and other comforts. All the inmates have the same model TV, the body molded of see-through plastic. He learns to measure the seasons by the calendar of televised sports. Somehow, the haplessness of Cleveland's franchises fits his predicament. It doesn't matter if they win or lose, as long as they eat up time.

He takes the courses he's allowed to take. Through Shawnee State University, he studies English comp, literature, and accounting. He takes his GED exam. He receives his associate of arts degree. He wants to go further but the budget gets cut. He works in a furniture factory and learns woodworking. He takes electronics classes and learns how to fix amplifiers and other appliances. He takes a class in home electrical wiring - to get started on becoming a licensed electrician on the outside. For his guitar playing, he studies the jazz masters, people like Wes Montgomery and George Benson, going all the way back to the crossroads, the blues. He forms a bunch of different bands and singing groups - part of his rec-department duties is overseeing the musical equipment. He contributes two songs to a state-financed album of children's lullabies - he writes, arranges, plays all the instruments, directs the singers, records and mixes it himself. (To his supreme embarrassment, a furor breaks out in the local press when the CD comes out and his status as a sex offender is discovered.) To enrich his skills as a painter, he studies the Old Masters. Da Vinci, Vermeer, and Rembrandt are his favorites. He likes the way they always have something real shiny in the picture that makes it stand out with the dark backgrounds. He also likes Salvador Dalí, whose absurdist abstract realism seems to fit his situation and his mind-set perfectly.

Towler does his best to watch his diet and stay healthy. They give you a lot of starch at every meal; he tries to stick to the proteins. His favorite fare is canned salmon mixed with contraband salad and vegetables. You can get almost anything in prison, except good fruit. (What little there is - apples, oranges, the occasional hard pears - quickly becomes custody of the resident hooch makers.) He loves playing basketball. He plays pretty much every day until he gets up in age, around forty-five. He is the guy driving to the hole, a power forward like Charles Barkley - don't get in his way. There are leagues; every game devolves at some point into a scuffle. One year in Lucasville his team wins the championship. He joins a football team, too. It is kind of like

TheLongest Yard, except they won't let them play the corrections officers or leave the front gate. The COs are pretty much what you'd expect. Some racist shits and some good human beings. Some of the females are nice, too. They have their pick of the inmates. You'd be surprised how much nookie goes on.

Incredibly, he is never seriously ill or injured. He pulls a muscle in his left calf. He chips a tooth on somebody's head playing basketball; the state dentist gives him a crown. He has a few colds, but never any food poisoning. A lot of guys cook stuff in their cells and try to save the leftovers; the place is crawling with germs. When he thinks about it, he is living in a bathroom, literally. His bunk is in the same room as his toilet/sink combination. The ventilation is bad. The reek can be powerful and lingering.

Over the years there are literally hundreds of cellies. One night. A month. Two years. They go home, they are transferred to another prison, they go to the hole and never return. He tries not to keep track, neither of the faces nor of the time. He is not a maker of hash marks. His sentence is infinite, there is no purpose in mocking himself this way.

His all-time worst cellie is called Chicken Saw. Don't ask how he got that name. He's a bully. He's shorter than Ray, but he's a muscle freak - does push-ups, sit-ups, jumping jacks in the cell all day and all night long, grunting and sweating and stinking. He's the one who gets caught with the shiv.

The all-time best cellie is the guy who dies. His name is Jackson. He was a welder on the outside. He is diagnosed with a 90 percent heart blockage. He is given thirty days to live but lasts almost three months. Towler teaches him how to paint. The last time Towler sees Jackson, they are bringing him out of the cell on a stretcher, loading him onto the back of one of the golf carts they use for an ambulance. He has a look on his face, this strange scared look. He asks Ray, "Am I going to be all right?"

"Either you're going to see Jesus or you're going to be back here," Towler tells him. They'd talked about this many times. "We both know which is better."

That was a tough day, one of many tough days. Many, many tough days. Pretty much all of them endured without the comforting touch of another human being; all of them endured without the feeling that there is someone squarely on your side - no one to love and no one to love you. Towler is alone in there. And everyone thinks he is someone he is not.

You look in his file, he knows the first impression you get. But he can never let himself believe that somebody can just look at him and say: "He's a rapist." Of course, guys always ask. They're like, "What are you in for?" If he tells them, they frown at him like he's a scumbag.

He thinks about escaping. How many times does he look at that fence, that gate, that barbed wire and think, Shit, man, I can get over that no problem. I can find a way to escape. I'm a pretty smart guy.

But he always puts those thoughts away. If I choose to run, nobody will believe I'm innocent. Once you leave, you're marked. People are like,

"If you're innocent, why did you run? If you're innocent, you would have stayed and fought."

© Michael EdwardsRay Towler

In 1993, after he is turned down for parole, Towler is visited by a dream. It will follow him from Marion to Grafton to the farm, across the years, through the dark prison nights.

He's in a long corridor - splendid and regal, like a castle or something, a palace fit for a king.

He is walking and walking.

There is nowhere to rest. There is nowhere to sit down. He feels like he must be going somewhere but he doesn't know where.

Finally he comes to a door.

He pulls the golden handle. He steps through.

Into another long corridor.

Walking and walking.

Endlessly walking.

In 1995, everybody in Grafton was glued to their identical, prison-approved, Visible Man television sets, watching the O. J. Simpson murder trial.

One part of the proceedings had Towler and his fellows riveted.

DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid. The unique genetic fingerprint that distinguishes each human from every other. Given the proper sample, a person could be identified with nearly 100 percent accuracy.

In 2001, following DNA tests on old evidence, a fellow inmate at Grafton, a convicted rapist, is exonerated by a judge and set free. Towler redoubles his efforts to sell paintings, hoping to build a legal fund.

In 2003, the Ohio legislature passes a bill allowing qualified prisoners to request state-paid DNA testing. Most cases are denied or indefinitely delayed. Incredibly, Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court judge Eileen A. Gallagher takes an interest in Towler's case. She appoints a lawyer free of charge.

In 2004, after consulting the Ohio Innocence Project - newly founded by Mark Godsey, a former federal prosecutor turned University of Cincinnati law professor - Towler's attorney gets the state to agree to send the evidence from Towler's twenty-three-year-old case to a lab for DNA testing. Three envelopes are shipped: One contains two pubic hairs recovered from the victim's pelvic region; one contains scrapings from under her fingernails; one contains the panties she was wearing beneath her yellow jumper.

When the evidence arrives at the lab, two of the envelopes are empty.

Contrary to the testing recommendation Professor Godsey gives Towler's lawyer, the lab conducts a type of test that turns out not to be sophisticated enough to detect any evidence of male DNA in the panties. The lawyer is notified of all of these findings in writing.

But not Towler.

He doesn't know what the heck's going on. He's at the Grafton Farm. Mentally, he's rubbing his hands together:

Okay, it's only a matter of time. Two weeks pass.

A month. No word.

He starts to get worried. He tries to call the lawyer but he can't connect.

More months pass.

Now Towler's all tore up. He's pissed.

Why can't this fuckin' guy call me back? One day on the phone, he's venting to his niece, Tiffany. She volunteers to go in person to the lawyer's office, where she learns the truth.

Towler feels like that scene in the movie

Full Metal Jacket, where all the guys in the barracks wrap bars of soap in their towels and beat the crap out of Vincent D'Onofrio.

Four more years pass.

Towler writes letters to judges, senators, congressmen, anyone he can think of. He writes a letter to the home office of the Innocence Project in New York, founded by the well-known legal activists Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld. They refer him to the Ohio office.

Professor Godsey sees Towler's letter. Towler doesn't know it, but he is already uppermost in Godsey's mind as Godsey works with

The Columbus Dispatch on a newspaper series exposing the flaws in Ohio's DNA testing system. Together with reporters from the paper, Godsey's volunteers, most of them law students, identify more than three hundred cases that could be fruitful to investigate. Thirty inmates are short-listed as strong candidates for DNA exoneration; Towler is at the top.

With Godsey's help, Towler formally reapplies to the court for further testing. In late 2008, with the benefit of rapidly advancing technology, a lab comes back with results showing that he was almost certainly not the rapist.

The prosecution is not satisfied. The assistant prosecutor assigned to the case (prosecutor Levenberg and Judge McMahon have since died) has a reputation as a hard-ass who fights for the sake of fighting.

By 2010, the technology has again improved. The DNA in the victim's panties is proven conclusively by the lab to be the product of a different man, not Raymond Daniel Towler. Towler is "excluded as the contributor of the sperm-cell DNA sample in this case," according to the findings of the Orchid Cellmark forensics laboratory, one of the nation's leaders in DNA testing.

Meanwhile, Towler waits. He has no idea what is going on. The whole thing is eating him up.

One night after lockdown, he finally gives up hope.

I can't take this no more, man, he tells himself. This is all I can think of. I wake up and wait for it - are they going to call today? Are they going to say I'm free? Or is it going to be like every other time: Sorry, we lost your samples. Sorry, we used the wrong test. Sorry, the prosecutor is a total bitch. Sorry, sorry, sorry! And then he tells himself: I'm done. I can't worry about this no more. It's out of my hands.

At that moment a great weight lifts.

Ray Towler feels like he can breathe again.

Wow, he tells himself.

Maybe I should've done this a long time ago.

© Anthony DeMatteoray towler self-portrait

, his attorney gets the word. Towler still has no clue. He's in his cell when the shift sergeant approaches, acting all friendly. "You have a call," he says.

Towler is suspicious. Usually this dude is a butthole. "What's going on?"

"I ain't supposed to tell you this ... but you're getting out tomorrow."

Towler doesn't believe him. It's the kind of mean thing this guy always does.

Towler is sitting behind a long table in Courtroom 23-A, overlooking the lake in downtown Cleveland. It looks exactly like the last courtroom he was in. It sort of gives him the creeps.

He is wearing a black sweater, a white shirt, and black dress pants. His shoes pinch. He hasn't worn civvies since ... probably since his mom's funeral, back in '84. Today is May 5, 2010. Someone tells him it's Cinco de Mayo, a Mexican holiday that celebrates a hard-fought military victory. I can go with that, Towler tells himself.

Judge Gallagher asks Towler for his patience as she summarizes the case for the public record. He can't focus on what she's saying. It feels like the longest speech in human history.

"Raymond Towler was a wrongfully imprisoned individual," she declares for all to hear.

After bestowing upon him an Irish blessing (May the road rise to meet you. May the wind be always at your back ...), Gallagher steps down from her high bench and approaches Towler with extended hands. She fights back tears.

"Mr. Towler, you are free to go."

They lead him out of the courtroom, a celebratory whirlwind gathering family and well-wishers as it goes. There is a press conference. People shout questions.

He hasn't slept a wink. His mind is so full of stuff, it feels empty, the way all the brilliant colors of the rainbow, mixed together, make black.

Twenty-eight years and eight months.

He doesn't know what to say.

All he can think about is pizza.

Towler spends his first night of freedom with his brother in their mom's old house. He can't even shut his eyes. He has so much to do. My lists have lists. He needs a Social Security card, a driver's license, a photo ID, a bank account, all the stuff people have. There are appointments with lawyers - there is a settlement due; more than forty grand per year of incarceration is guaranteed. If he wants more, he'll have to fight the state over lost wages, pain and suffering, the usual. He will fight. There will be money, probably a couple of million, but not yet. Another item on the list: Find a job.

He rises at dawn his first morning, as he is accustomed. Everyone else in the house is still asleep. Birds are chirping. It is nice and cool. He sticks his head out the front door of the house, sniffs the suburban air ... but he can make himself go no farther. It's like there is an invisible barrier.

On the fourth morning, he musters the courage to walk to the store himself. A container of orange juice never tasted so good.

He is like a new person, starting all over from where he left off. He's hoping to get in twenty more years. He tries not to think of all the time he spent behind bars as "lost." Instead, he tries to focus on the positive. Sometimes he finds himself standing for a few moments in the bathroom, sort of marveling. For three decades he lived in his bathroom. Now, after living with his cousin Carole for a few months, he lives in his own apartment (another of his life's belated firsts). No longer must he shit where he eats and sleeps.

Driving around the city, his new license in his pocket, Towler notices all the changes everywhere. There are fancy new street signs and crosswalks, a zillion new buildings downtown. He's still timid about nosing into traffic; he'll sit forever at a left turn, letting everyone in front of him go. Frequently he finds himself lost. Somebody gives him a GPS, but he doesn't know how to use it. Somebody else gives him a BlackBerry; he's pretty good with that. He gathers possessions: a guitar, a sax, an easel, an amplifier (he has to fix it himself using his prison-learned skills), and a bass guitar, for which he shells out $400 because the band at the church needs a bass player.

Another thing Towler notices is the number of nonwhite faces everywhere. When he gets his job in the mail room at a big health-insurance company downtown, he is pleasantly shocked. There are coworkers of every hue; it almost feels like race doesn't exist in the same way anymore. His immediate supervisor is a big and pretty white lady. He could swear she's kind of flirting with him.

That's another thing: women. It's tripping him out the way they so aggressive today. Before, they would just kind of wait around, and you would make your move, and they would make it known what their answer was. Now they come straight up to him and it's like, "I think we should date, Raymond." Women are more bossy now, too. He is at this art festival with this one gal, and she's telling him, "You need to do this," and "You need to do that." Finally Towler smiles real big and says, "Really? Do I really have to do all of this? Is that, like, an order?"

In restaurants he feels responsible to read every word of the menu. He calls the tortillas "little pancakes." He marvels over this wonderful offering called a western omelet; he thanks the waitress profusely for taking the time to list the ingredients. While he's eating at a chain steakhouse on the outskirts of a mall parking lot, a guy in a suit comes to the table and asks how dinner is going. Ray wonders politely who he is to be asking ... and is flattered to learn he is the manager of the entire place! When his favorite lawyer comes to town - she was on the conference call in the sergeant's office - he tries to take her to a nice Mexican restaurant to show his gratitude but ends up taking her to a taco stand by mistake.

Wherever he goes, everything is computerized. The gas station, the convenience store, the hardware store: Swipe this, enter that code, do it yourself. Automated supermarket checkout? You wonder why people are crying about needing jobs. It used to be anybody could get a job in a grocery store, from teenagers on up. Likewise cars: He used to be able to fix anything. Now he'd have to go to school all over again to learn fuel injection and the other computer-driven stuff.

So many choices. Which car insurance. Which cereal. Which deodorant, toothpaste, toothbrush, soap, shampoo. Rows and rows of products. Varieties, sizes, colors. Which is cheaper? Which is better? What's the best buy? Which gum to chew? When he went into prison there were, like, two kinds of chewing gum. Now there are a zillion. One of the small gifts he gives himself is trying all the gums. "I can spoil myself a little so long as I stay within my means," he says. Papaya juice! Kiwi and strawberry nectar! Green tea! Arnold Palmer - he was a golfer when Towler went down. Now he is a drink, sweet and so incredibly thirst quenching.

He loves work. He got out May 5 and started working June 21. Hell, I've been vacationing for thirty years. He wears a smock and pushes a mail cart. He stops at all the cubicles, greets everyone with his friendly smile. Ray even loves commuting to work, especially now, in his new car, a black Ford Focus. He's like a sixteen-year-old who can finally drive himself to school. It costs almost the same to park as it does to take the train.

One day before he gets his car, he is sitting on the train with his commuting buddy, this German girl he met. They're stopped; a cop gets on the train, this big white guy. He stands for a minute kind of looking around - he keeps looking down the aisle, but then his eyes keep returning to Towler. Then the cop says, "I want to check everybody's ticket."

Towler's like, What the fuck? He kind of has a flashback almost, like, What: You gonna try to pat me down or something, man? Luckily the German girl notices the look on Towler's face. He has told her his story. That's one great thing. Everywhere he goes people recognize him from the news. Or if they don't recognize him, they've heard of him - this guy whose life was stolen by the state. Everyone feels bad for him. And when Towler shows he doesn't feel bad for himself, that he's not going to be a resentful complainer about the whole thing, everyone wishes him well ... he is an easy guy to like.

Of course, the cop on the train doesn't know all this.

Towler's eyes bulge. The German girl leans over and whispers, "He's just doing his job, Ray, don't worry."

The moment passes.

At eleven o'clock one evening shortly after his release, Towler is feeling hungry. He gathers up the keys to his car and drives off into the dark, in search of a three-piece chicken dinner.

It's the first time he's driven anywhere at this time of night by himself. He is careful to drive the speed limit. The windows are down, the air is humid and smells of tree pollen, the sounds of summer filter past. For three decades they locked him down without fail at 9:00 P.M. Unless there was a fire drill, he never got to see the night.

He drives down Lorain Avenue, past some restaurants and clubs. He looks at all the people, just checking things out. As usual, he kind of knows where he's going but he kind of doesn't.

He makes a wrong turn. Maybe two. He finds himself ...

Down in the Valley, in the Rocky River Reservation.

His heart begins to pound.

Dang, man, it's kinda dark. It's like the shark theme from Jaws is playing.

You need to get up outta here fast.

Towler pulls it together and finds his way out. He kind of laughs at himself, at his momentary freak-out.

Why should I be worried? I'm an American. I got my rights. I ain't doing nothing wrong. All his life, he tried to be a stand-up guy. He was a dutiful son, a good relative, a U. S. Army veteran. He respected the law. He did all the things he was supposed to do.

His reward: three decades in prison.

Since he's been out, everybody asks the same question. "Are you mad for what they did to you?"

And the answer is: "You know, I kind of am. But it's over now. I have to look ahead."

On 117th Street, Towler finally comes across the place he's been hunting. He orders his three-piece fried with a biscuit.

Then he drives back to Cousin Carole's.

He takes his food into the backyard. He chews and watches the stars. He listens to the crickets and the night birds. This is one thing I always wanted to do, he tells himself.

And so he does.

...with liberty and justice for all...

yup...