Though a nickel will not buy much today the element nickel is invaluable to our contemporary way of life. Without access to this nonferrous metal, much of what we take for granted would not be practical or in many cases possible. Automobiles would be fragile - hitting a pothole would, as in very early cars, often break an axle. Internal combustion engines could not be depended upon and would also weigh a great deal more per unit of horse-power than the motors we are accustomed to. Airplanes, if they could be made to fly (the Wright brothers used a motor that took advantage of nickel steel's superior strength to weight ratio), would be terribly unsafe. Jet powered flight would be impossible - the strength that nickel gives to steel at high temperatures made this type engine feasible. No buildings could scrape the sky without nickel's contribution; steel bridges would be massive, ugly and corrode rapidly as well. In essence, our world would appear and function much as it did one hundred years ago, for it was in the late 1880′s when nickel-steel became a product.

The discovery of this nickel-steel key to our century is quite fascinating. John Gamgee, an eccentric inventor, had succeeded in convincing U.S. government officials that victims of a yellow fever epidemic, then sweeping the south, could be brought back to health by living in a cold environment. Gamgee's plan was to develop a refrigerated hospital ship which could travel from port to port, pick up victims, and freeze the fever out of them. Aiding Gamgee in this enterprise was Samuel J. Ritchie, a carriage manufacturer, who had recently met the inventor by chance (their Washington, D.C. hotel rooms were next door to one another). With Ritchie's help, Gamgee received a promise from the Senate Committee on Epidemic Diseases for an appropriation of a quarter million dollars if the inventor could prove that a workable refrigeration system was possible. A machine shop at a local Navy shipyard was made available to Gamgee so that he could construct and demonstrate his cooling apparatus to the committee.

In 1876 (when this took place) refrigeration was a very new capability and Gamgee soon encountered a problem with his proposed device - he could find no material that would hold up to the pressure his machine generated. Normal cast iron, being porous, allowed his cooling agent (ammonia) to escape. Undeterred, Gamgee began mixing other metals with iron. After several weeks of disappointing results the inventor turned to his new found friend and asked: "Ritchie, did you ever notice the meteorites at the Smithsonian Institution?" The carriage maker said that he had, and Gamgee went on: "Well, we have no metallic iron on earth produced by nature in that form, and those meteors have all fallen from the skies, or have come from some other world. They nearly all contain nickel. Tomorrow we will send over to Philadelphia and get some, and try it. . . . try this metal as an alloy with iron, and see if we can imitate nature in duplicating the meteorite, as we are trying to imitate nature in the production of artificial cold for the yellow fever patients."

Seventy-two samples of nickel-iron were produced, each blend with a half-percent higher nickel content. The batch that was eight percent nickel proved so hard that neither file nor chisel could alter it. Recalling this event later, Ritchie relates that Gamgee threw up his hands and shouted: "Eureka! I have found at last an alloy strong enough and hard enough to resist anything and close enough in texture to resist the escape of any form of gas!"

The two men, excited by this find, invited the Senate committee to come take a look for themselves. Duly impressed, it seemed certain that the committee would give the go ahead on Gamgee's project. Unfortunately, the inventor chose this occasion to differ with the committee chairman over the cost and management of the proposed ship. The arguing continued. The weather cooled. The mosquitoes died and so brought the yellow fever epidemic to an end. Public attention turned elsewhere leaving Gamgee with no funds to continue his project. Ritchie returned to his Akron, Ohio carriage business undoubtedly thinking . . . "well, that's that." He could not have known what a profound effect his experience with Gamgee was to have on his future.

In 1881, Ritchie had need of second growth hickory to sustain his carriage business. Land was cheap in Ontario, so he went there to find his trees. While there, he also found iron ore, so he purchased fifteen thousand acres inclusive of mineral rights. To get his lumber out, as well as the iron ore, Ritchie needed a railroad. Through an impressive bit of wheeling and dealing, this entrepreneur had, in 1885, a major interest in the Central Ontario Railway and a working iron mine. Things did not pan out as Ritchie expected. His ore had such a high sulfur content it was almost worthless. About ready to give up mining and sell his interest in the railroad, Ritchie happened across some ore samples taken from Sudbury - a region that was near the operation he had underway. Analysis of these samples indicated a seven percent copper content. Ritchie immediately sent a deputy to Sudbury, then went himself. Ritchie returned owning some properties and holding options on almost one hundred thousand acres in the area. Again Ritchie was to face disappointment, though this time short lived. His new ore would yield no pure copper; another element refused to separate from the metal he sought. Further testing of the ore revealed the reason for its unexpected behavior. In Ritchie's words:

The discovery of this nickel in these ores . . . was unexpected news . . . . We had no suspicion that they were anything but copper ores. This discovery changed the whole situation . . . . As the world's annual consumption of nickel was then only about 1,000 tons, the question was what was to be done with all the nickel which these deposits could produce. I at once recalled . . . John Gamgee in the Navy Yard at Washington . . . and it occurred to me that nickel could be used with success in the manufacture of guns and for many other purposes as an alloy with iron and steel.This occurred late in 1886. Ritchie fired off a letter to the famous gun-maker, Krupp, in Essen, Germany, telling him of the experiments Gamgee had performed a decade earlier. Krupp replied that there was not enough nickel in the world to warrant experiments which pointed to greater use of the element. Ritchie knew better. By 1890 things had changed considerably; a nickel pickle was on the world's platter and little would remain the same.

The "arms race" as we know it began at this time. So impressive was the strength of this material for military purposes that in Glasgow (1890) the October 27, the Herald ran this prophetic statement:

. . . . "When the irresistible nickel plated breech-loader confronts the impenetrable nickel plated ironclad then indeed . . . war as a fine art will come to an end."The Herald article was based on then recent tests of nickel steel armor plate at Annapolis.

On April 24, 1898, Spain declared war on the U.S. The war ended December 10 of the same year. Two major encounters occurred in this war - the Battle of Manila Bay and the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Almost the entire Spanish fleet went to the bottom in these altercations. The United States lost one sailor. Nickel steel armor made the difference. The U.S. Navy had proven its metal. Naturally, other nations wanted the same protection for their own ships. The demand for nickel steel rose sharply and continued to rise as more and more applications were found for it. As mentioned earlier, the automobile industry was facilitated by this material. In the words of an early auto builder, Elwood Haynes:

Since the first attempt to build automobiles, early in the 90′s, experimenters have had difficulty in getting materials suitable for the purpose. Steel of high tensile strength was employed but the results were not satisfactory. Lower carbon steels were tried, but they lasted only a few weeks, or months, and then broke off short. Swedish iron did not break, but when the first hard bump was encountered it took a set and the wobbling rear wheels indicated what had happened. Finally a steel of moderately low carbon was introduced which gave only fair results, and if the car was driven for any length of time over rough roads, this also crystallized and broke off. Nickel changed all this.Nickel would alter conditions far more than it had in 1907 when Haynes addressed his audience of mechanical engineers at Indianapolis, Indiana. The following year (1908) Model T's started rolling off the line. From here on, the pace of social change got quicker, and, as a consequence of building and operating the equipment that drove this change, our planet's air became thicker.

There is great irony in civilization's meteoric path to the present state of affairs. Recall that Gamgee was inspired by the physical properties of meteorites to try nickel as an alloy with iron. Gamgee's results caused Ritchie to recognize the potential of this then scarce metal when he later stumbled upon a huge quantity of it. What no one was to realize for quite some time was that the nickel, copper, iron, platinum, iridium, gold, silver, and other metals extracted from the ores of Sudbury had arrived there very suddenly about 1.7 billion years ago. In a very real sense, we have built high-tech from a meteoroid wreck. The large quantity of nickel available from this debris (that once constituted an asteroid estimated to have been two and one-half miles across) allowed Canada to dominate world production of this metal for better than half a century. There is, though, a very large price being paid for salvaging this mega-meteorite scrap - acid rain.

The dangerous drop in the pH value of rain water can not, of course, be blamed on this one metal refinery. Sudbury is, however, an excellent example of why our showers are turning sour. A nickel/copper smelting plant, owned by International Nickel (Inco), in this region has the unwanted distinction of being world champ in sulphur dioxide (SO2) emission. This one operation spews over six hundred thousand tons of SO2 into our air annually - about two times the yearly output of Sweden, a nation that now has around twenty thousand acidified lakes, one fifth of which no longer contain fish. Combined SO2 emissions from eastern Canada's non-ferrous metal industry amounted to over two million tons in 1980, forty-five percent of Canada's total SO2 contribution, east of Saskatchewan. Mining landed asteroids is definitely not a practice that will improve our present environment. There is, though, a way to get ourselves out of the "picklish" situation an abundant supply of nickel allowed us to get into.

The demonstrated fact is that many industrial processes do not blend well with the workings of a biological system. Solution? Expel those industries known to be harmful to our environment. This is not really a drastic remedy. Mining and processing materials in space are desirable from a long-term environmental, economic, or political outlook. Why, then, is there not a major project underway to rapidly relocate these industries which harm our environment? Part of the answer is found in the newness of such an option, but the principal reason a high priority has not been placed on this type of space development is the arms race. This dangerous contest saps the talent and resources needed to develop an infrastructure which would support space based industry.

The arms race, however, is very much a product of discordant global attitudes. Unless we soon learn to work in concert toward a harmonious relation between ourselves and the rest of nature, this meteoric rise in capability we have recently experienced will end with a catastrophic crash of civilization. A downfall that, if caused by continued industrial malpractice or a nuclear confrontation over controls of limited resources, will have a tremendously devastating impact upon all of Life on Earth.To survive, we must do better.

Part B

There is though, another agent which could destroy civilization and do great harm to the environment, a large consignment of elements from space. Such deliveries are not as uncommon as was previously thought, particularly during the past twelve thousand years. Much evidence suggests that humanity witnessed, and was affected by, the break-up of a very large comet over this time period. Astronomers, using data gathered on meteor showers, have established that this debris had about the same orbital characteristics five thousand years ago as it has today. The stuff orbits the Sun in roughly three and a third years and while doing so crosses our planet's orbital path twice. Clearly the potential for collision is real and has been realized a number of times in the past - most recently in the eighth year of this century.

Study of the "Tunguska event" has shed considerable light on the subject of impact phenomena. Interestingly this illumination would probably be much weaker were it not for the value of nickel and other metals that often comprise a meteorite. The newly established Soviet government was strapped for funds in 1921; warfare had ravaged their homeland over the previous six years and it was now time to rebuild. Any plan that held promise of producing a lot of rubles quickly must have seemed attractive to Soviet officials. American geologist/mine engineer Daniel Barringer's quest to extract the five to fifteen million tons of meteorite metal that, he believed, was buried beneath "meteor Crater" in Arizona had attracted considerable attention about the world. The prospect of finding over a billion dollars worth of metal in the bottom of a hole was quite intriguing - a natural "pot of gold" story. Also, much scientific debate had been sparked by Barringer's activity. Most geologists favored a more down to earth explanation of this crater - the planet had simply blown off a bit of steam there.

Barringer had finished his first boring episode in July of 1908, totally oblivious (as was most of the world) to the fearful excitement that still gripped those who had witnessed a terrifying arrival of space debris only weeks earlier. Though the outside world would remain ignorant of the Tunguska fall for two decades, there were reports, printed in several Russian newspapers, of some unusual phenomena which occurred in remote Siberia on the last morning of June (1908). One of these stories must have later seemed extremely attractive to the cash poor Soviets. This particular report stated that all the commotion had been caused by the landing of a large meteoroid which fell very close to a railway. The story indicated that the meteorite was only partially buried and might be as much as six cubic sagines in size. Six cubit sagines translates into a twelve foot, nine inch cube of meteorite material - a hunk of potentially valuable stuff that could be hoisted onto a railcar and pulled to wherever. Barringer was drilling away again in 1921 and largely due to the publicity this activity received, it was now widely known that meteorites often contained, in addition to nickel, diamonds, platinum, gold and other materials of high monetary value. These baubles from space could also fetch a good price from museum collectors who would pay dearly to keep such valuable pieces of information out of a furnace. In light of the circumstances, it is easy to see why the Soviets chose to fund, as one of their first scientific expeditions, a search for meteorites.

As it turned out the only people in North America or the Soviet Union that made a lot of money from a meteorite in the twenties were those who had no idea they were digging up space debris - the Canadians mining at Sudbury.

The real value of these searches proved to be in the wealth of information uncovered. Much to Barringer's disappointment it was learned that a relatively small object would excavate a lot of earth and rock as it slammed into the planet. This prospector saw his five to fifteen million ton jackpot shrink at least ten fold. Furthermore, he was informed that most of the one-and-a-half, to half-million ton mass which created his crater had been liquefied in the process. This meant that what celestial material had not splashed out of the feature was widely distributed within it, making a profitable mining operation very doubtful. Barringer did not accept astronomer Forest Ray Moulton's conclusions, however, he could not disprove them. Financial backers of the mining project, who had commissioned Moulton's study, withdrew their support. Barringer, whose tenacious spirit helped prove that large craters could result from meteoroid impact, died of a stroke after three months of heated debate over Moulton's 1929 papers. This researcher/prospector contributed much to science over his sixty-nine years.

Soviet scientist Leonid Kulik was not so much frustrated by what his research was revealing as he was perplexed. Though the news clip which justified Kulik's 1921 expedition to remote Siberia had proven to be almost totally inaccurate, the trip had been intriguing. Descriptions given by actual witnesses of the 1908 event piqued Kulik's curiosity to the point where he had to find out what really happened in this sparsely populated region of the world. This researcher dug in, and after six years of fact gathering he finally persuaded the Soviet Academy of Science that it was time for another expedition.

Much of the information Kulik had been compiling came from fellow researchers doing work in that part of Siberia. Most intriguing were stories relayed back from scientists working among the native Tungus people. This had posed somewhat of a problem for Kulik, as few scientists in the academy gave credence to tales told by those they considered to be primitive, backward people. What finally tipped the scales in Kulik's favor was a report prepared by a former head of the Inkutch Observatory, A.V. Vognesensky. Vognesensky combined the data Kulik had gathered with 1908 seismic data recorded at Irkutsk and concluded that:

. . . it is highly probable that the future investigator of the spot where the Khatanga [Stony Tunguska] meteorite fell will find something very similar to the meteorite crater of Arizona; i.e., from 2 to 3 kilometers around he will find a mass of fragments that were separated from the main nucleus before it fell and during its fall. The Indians of Arizona still preserve the legend that their ancestors saw a fiery chariot fall from the sky and penetrate the ground at the spot where the crater is; the present-day Tungusi people have a similar legend about a new fiery stone. This stone they stubbornly refused to show to the interested Russians who were investigating the matter in 1908. However that may be, the search for and investigation of the Khatanga meteorite could prove a very profitable subject of study, particularly if this meteorite turned out to belong to the iron class.This is why Kulik was a bit dumfounded when, in 1927, he actually found the spot he had sought. The devastation was quite obvious; over seven hundred square miles of dense Siberian forest had been scorched and flattened. There was, however, no crater.

Kulik's find revealed that colliding space debris could do a great deal of damage yet leave little long-term detectable evidence to indicate that an impact had occurred. Some implications of this fact were recognized by a few investigators almost immediately. Astronomer C.P. Olivier, writing of Kulik's discovery for Scientific American, stated in the July 1928 issue:

In looking over this account, one has to admit that many accounts of events in old chronicles that have been laughed at as fabrications are far less miraculous than this one, of which we seem to have undoubted confirmation. Fortunately for humanity, this meteoric fall happened in a region where there were no inhabitants precisely in the affected area, but if such a thing could happen in Siberia there is no known reason why the same could not happen in the United States.Olivier's statement would have certainly invoked a nod from any reader who had perused an essay published the year before by Franz Xavier Kugler. Kugler was a Jesuit priest who had devoted much of his life to the study of ancient cuneiform astronomical tablets. Like other philologists, Kugler had earlier in his career decided that some of the unearthed tablets he deciphered were purely fictional. This scholar's 1927 essay, "Sybillinischer Sternkampf und Phaethon in naturgeschichtlicher Beitrage" (The Sybilline Battle of the Stars and Phaethon Seen as Natural History), was published two years before his death. Apparently the emerging realization of how destructive a meteoroid impact could be, combined with his life-long study of ancient astronomical texts, prompted Kugler to re-evaluate his earlier interpretation of some of the clay tablets deciphered by him. The importance of Kugler's work stems from the fact that he was reading unearthed documents, not handed down tales. Researchers are, understandably, reluctant to put much faith in stories that have been passed along over many generations. Both the Sybylline Oracles and the story of Phaethon fall into this category. Though other sources establish these traditions as ancient, no really early written version of these works has been found. By pointing out features that such stories had in common with unearthed cuneiform texts, Kugler was able to shed some light on the original core of these tales. In Kugler's opinion, the destructive impact, around thirty-five hundred years ago, of a sun-like meteor, which he found chronicled on clay tablets, provided the inspiration for the Sibylline Battle of the Stars and the Phaethon legend.

Actually, as we learn more of the phenomena an impact event is capable of producing, many ancient accounts are appearing less incredible. For instance, several cultures about the world have retained legends which associate cold weather with fire coming down from the sky. Only a decade ago if any credence was given to such a tale, the assumption would have been that the story was inspired by vulcanism. While it is certainly possible that some legends do stem from volcanic activity it is no longer "scientific" to make such an assumption. Researchers now know that an impact event could produce a darkening of the sky and so cause a steep drop in temperature.

The Sibylline Oracles employ less metaphor than many ancient accounts and so provide some rather succinct lines for the reader to ponder:

And then in his anger the immortal God who dwells on high shall hurl from the sky a fiery bolt on the head of the unholy: and summer shall change to winter in that day. And then great woe shall befall mortal men: for He that thunders from on high shall destroy all the shameless, with thunderings and lightnings and burning thunderbolts upon his enemies, and shall make an end of them for their ungodliness, so that the corpses shall lie on the earth more countless than the sand.The above is from a 1918 translation by H.N. Bate. Reverend Bate, as did most scholars of that time, perceived these lines as nothing more than eschatological embellishment of the apocalyptic theme. The phrase, "and summer shall change to winter in that day," did not need to make sense from his point of view; Bate simply noted that in another version (Book VIII) of these oracles, a parallel passage has God changing winter to summer. The interesting factor here is that to someone with no knowledge of impact phenomena, the notion that it should become cold as a result of God throwing fire from heaven is absurd. From a "logical" perspective it would be easy to assume that a scribal error produced this nonsense and a simple swap of word position would correct it. In a translation by Milton S. Terry, published in 1899, a reader can thumb to Book V and find essentially the same lines as those quoted above from Bates' translation. The only real difference in Terry's version has: "And in the place of winter there shall be in that day summer." This "correction" was probably not made by Professor Terry but by a Venetian scholar, Aloisius Rzach. Terry based his English translation on Rzach's Greek version, published in 1891, because it was in his words, "The latest and most improved edition of the Greek text of the twelve books now extant . . . ." However, Terry does caution his readers that Rzach's ". . . work has not escaped criticism, especially on account of its numerous conjectural emendations, . . ."

The assumption or premise that our ancestors were only referring to phenomena which we, also, are familiar with has produced considerable distortion in our view of the past. Consider the term thunder-bolt. A large stony meteoroid will often break up violently in the atmosphere. If the object is large enough to reach into the lower atmosphere, an observer will see a blinding flash of light followed by a loud crash of thunder. Often a large dark cloud composed of oxides of nitrogen and debris from the object will appear. This cloud can be highly charged and so cause conventional lightning to ensue. Scientists call such an arrival a bolide. Technically the Tunguska object falls into this classification because its energy was released several miles above our planet's surface. A problem is that most people who have translated ancient texts had never witnessed a large bolide and until fairly recently, few, if any, would be aware that such a phenomenon could occur. A term like thunder-bolt, to people unfamiliar with impact phenomena, easily equates with lightning bolt. As a result, many ancient accounts of impact phenomena have been read as descriptions of jolly good storms.

At present the academic community is in the process of a major alteration of world view. The picture of a placid, slowly changing environment is being replaced by the image of a biosphere periodically thrown into chaos by major impact events. Though debate continues on the degree of influence, it is now widely accepted that past collisions with extraterrestrial objects have played a role (likely a major one) in biological evolution. What has yet to be adequately investigated is the part past impacts have played in human social evolution.

Until very recently, there was little evidence to support Plato's contention, particularly his assertion that these events occurred "at stated periods of time." What has now moved the words of this old Greek philosopher from the improbable to plausible realm is a contemporary awareness of the numerous large objects that cross our planet's path - especially the debris mentioned earlier that is associated with comet Encke.

British astronomers Victor Clube and Bill Napier present, in The Cosmic Serpent (1982), a strong astronomical based argument which contends that, due to its orbital characteristics, the progenitor of comet Encke quite likely caused humanity a great deal of grief in the past. How large this comet was when it first fell into an Earth-orbit-crossing path is not known. It is possible that this object had more in common with a beast like Chiron than it did with the normally small, long-period comets. Chiron's size is about one-hundred miles across. It presently has an unstable fifty-one year orbit which keeps it between the paths of Saturn and Uranus. The object has exhibited comet-like activity to astronomers and because Chiron's orbit is not stable it could be pulled into our region of the solar system a few thousand years from now.

It is difficult to truly appreciate the visual phenomena that such a large object could produce as it neared the furnace of our solar system. Gases from such an object might produce a coma as large as the Sun and a tail which would span the orbits of the inner planets. In close proximity to Earth, the size of such an apparition would make the Sun and Moon appear as dwarfs. Combined evidence suggests that our ancestors witnessed such mega-comet activity and were influenced psychologically, as well as physically, by the ensuing phenomena such a large interloper could, and apparently did, produce.

One way the reader can realize the collective ignorance, and yet appreciate how fast things are changing in this area of research, is by comparing the number of objects Clube and Napier associated with comet Encke in 1982 to the number known presently. In The Cosmic Serpent, the authors list only one object, Hephaistos, as having once been part of the still active comet Encke. Hephaistos was discovered in 1978 and is one of the largest Earth-orbit-crossing objects found so far. Its six mile diameter (about the same as the hypothetical dinosaur slayer) is actually larger than comet Encke's estimated girth. As of now (late 1988), five objects in addition to Encke are identified with this group, with two more orbiting bodies seen as likely members.

The rapid population rise of recognized objects in the Encke group is a result of a stepped up effort to locate Earth-orbit-crossing objects in general. Prior to the 1979 discovery of hard evidence which indicated a link between mass extinction and impact generated phenomena, few researchers were working in this area. Most astronomers were studying features far removed from our solar system such as black holes and other galaxies, while geologists and paleontologists, in the main, were comfortable with the long held idea of an Earth that changed very slowly. What is presently taking place constitutes a change of view as radical as the altered picture which came from proving the Sun does not orbit about the Earth.Naturally, not all researchers are happy with what is transpiring - abandoning long-held assumptions is not pleasant, particularly when these beliefs served as corner stones to your research. This is though, where the true value of the scientific method comes into play. Once enough evidence is found to show a prior assumption false, that earlier belief will become passé, no matter how familiar and comfortable it had been. Understandably, a bit of verbal battling takes place before there is a general acceptance of a new world view and this process of hashing it out can appear quite confusing to a casual observer. One article might convey to the reader that, though impacts can cause mass extinction, our time period falls safely between such periodically recurring events so there is no reason for us to worry. Another paper might state: Yes major impacts occur, but they do not cause extinction because . . . Actually, a consensus has emerged among scientists who are in the forefront of this research. These investigators agree that mass extinction has been caused by impact phenomena, and that major impact events increase in frequency at thirty to thirty-three million year intervals. They also concur with evidence which indicates that the last bombardment episode spanned a few million years, around a date which occurred thirty-four million years ago. A recent (over the past two million years) rise in the rate of crater formation combined with the evidence for periodicity leads these scientists to conclude that we are presently within such a bombardment episode. Their contention is further strengthened by the contemporary presence of a larger than normal population of Earth-orbit-crossing objects. Stated simply, these researchers agree that the chance of a major impact happening in the near future is much, much greater than it was thought to be only a decade ago. This also means, of course, the probability that there have been fairly recent past impacts is also greater. In fact, the orbital characteristics of debris associated with comet Encke basically guarantees that significant collisions have taken place within the last fifteen thousand years.

Part C

The contemporary picture of pre-history has been pieced together with total disregard for the effects impact phenomena had on our ancestors. Obviously the image of our past will be much different when this newly discovered influence is factored in. As already mentioned, it is becoming clear that much ancient lore which has been labeled as pure fiction is actually rooted in fact. It should therefore, not be surprising to find that one of the most ubiquitous topics of folklore, "the fall of mankind," stems from the most damaging of recent impact events.

The notion that humanity at one time lived in a pleasant bountiful environment, where people enjoyed long lives free from warfare and arduous labor, has been shown by contemporary archaeological studies to be a pretty accurate description of late Pleistocene life-style. In his book How to Deep-Freeze a Mammoth (1986 English ed.), Swedish researcher Bjorn Kurten concludes a chapter on Pleistocene cave art by saying:

. . . One thing is evident, no matter how paradoxical it sounds: it is a materially as well as spiritually rich culture that is reflected in the painted caves; it is also a culture without wars and without heroes apart from the ordinary man and woman. And it was the tremendous productivity of the mammoth steppe that enabled it to flourish. No Stone Age people of the present day has so rich a material base. Then came the end of the Ice Age, and the great crisis. The spreading forests and the increasing warmth spelled death to many animals and thinned the ranks of others. And so man had to work in the sweat of his brow, his life span was shortened, cannibalism, slavery, and war became prevalent . . .Oh well, I am exaggerating. But it is true nonetheless.Actually, the only truth stretching Kurten employed here is his assertion that the spreading forest and increased warmth can explain the loss of so many animals. This is merely one theory among many that have been put forth in an attempt to pin down the cause of what is generally called the mega-fauna extinction.

The Swedish edition of Kurten's book was published in 1981; at this time the most popular hypothesis was Paul S. Martain's over-kill scenario. Simply put, this explanation attributes the demise of the large herbivores to our ancestors' hunting zeal. What gave this idea credence was a five thousand or so year gap between the youngest dated mammoth finds on the Euro-Asian continent and the most recent date for animals uncovered in North America. This hiatus seemed to rule out climate change as the culprit, and since there was little well-dated evidence of humans being in North America prior to fourteen thousand years ago, it appeared as if our forebears could have been guilty. Martain's scenario also squared well with a prevalent negative view of human nature. As ruthless hunters, we first eliminated the long-nosed plant eaters from the Old World, and when a path became available across the Bering Strait, we invaded a New World where it was especially easy to bop the animals, the poor beasts being naive and not knowing to fear humans. The New World animals' ignorance of "true" human nature seemed to explain why their decline appeared to have been more rapid than the supposed earlier disappearance of their more wily cousins in the Old World. Kurten obviously did not favor this over-kill hypothesis when he wrote his book, and, as more evidence comes to light, it now appears that humanity will be exonerated from this rap.

Presently, attention is again focusing on climate change as the phenomenon responsible for the mega-fauna extinction. The evidence, however, indicates that it was not a slow shift to warmer weather which did the large animals in, but a sudden shift to cold.

Over the past decade, significantly improved techniques for determining when some past event occurred have become available to researchers. The ability to obtain dates with less material and cross check them via other methods is rapidly dissipating the "fog" that formerly shrouded prehistory. For instance, there has been for quite some time now, evidence for very early human occupation of the Americas. The problem was, and to a lesser degree still is, the small number of early dating sites. Since such evidence was in conflict with the widely accepted notion of a late human arrival, these early dates were generally held to be suspect and probably due to natural contamination or sloppy procedures. Improved dating techniques, combined with a growing number of sites which date well before fourteen thousand years ago, have made it much more difficult to deny an early presence of humanity in the Americas. Similarly, a number of mammoths have been uncovered in the Old World which date much later than those previously found. Even though the quantity of such finds is low, the quality of dating is quite high, and they have been accepted as strong evidence that the large animals did not disappear from that part of the world significantly earlier than their cousins in the New World.

As mentioned earlier, an abrupt onset of frigid weather, known as the Younger Dryas cold event, is fast becoming the prime suspect in the mega-fauna extinction case. Suddenly, around eleven thousand years ago, glaciers which had been receding for several millennia were reestablished up to a thousand miles south of where they had been earlier. Modern dating techniques have, over the past few years, allowed scientists to determine that these glaciers formed and then dissipated in less than four hundred years - possibly within a century. The cause of this severely rapid flip-flop in climate is not yet known. There is, though, a very, very good possibility that the agent which formed the Carolina Bays produced this environmental crisis.

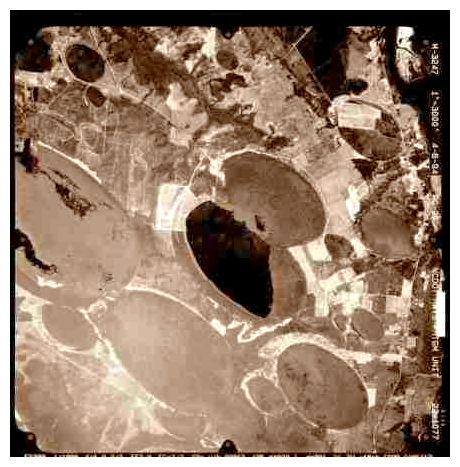

In 1930 an aerial survey covering around five hundred square miles of South Carolina coastal plain was undertaken. This mosaic of photographs revealed some quite unusual features - the area looked as if some outraged giant had blasted it with a colossal shotgun. Newly discovered impact craters were big news in the early thirties: some large structures had been discovered in Australia (Henbury Craters), and British explorer James Philby was, in 1932, led to find some impressive and actually fairly recent craters in the Arabian desert (Wabar Craters), by a guide who sang:

From Qariya strikes the sun upon the town;That same year geologist Frank A Melton and physicist William Schriever, both of the University of Oklahoma, had finished a lengthy study of the unusual features revealed by the flying camera two years earlier. They reported their findings at a 1932 meeting of the Geological Society of America, and these were published the following year in the Journal of Geology, under the title "The Carolina Bays - Are They Meteorite Scars?" Later that year (1933), Edna Muldrow captured the attention of Harper's Monthly readers with this opening paragraph:

Blame not the guide that vainly seeks it now,

Since the Destroying Power laid it low,

Sparing nor cotton smock nor silken gown.

What would happen if a comet should strike the earth? We do not like to dwell o that possibility, it is true; yet such evasion arises mainly because we are human and it is human to shun the unpleasant. So we bolster our sense of security by the assumption that what has not happened will not happen. This assumption is false. The truth is that the earth in the past has collided with heavenly bodies, and the more serious truth is that it may collide again.After informing readers of Melton and Schriever's work, Muldrow concludes her six and a half page article, "The Comet That Struck The Carolinas," with a rather graphic "if" scenario:

If the disaster of the Carolinas should repeat itself in the vicinity of New York City, all man's handiwork extending over a great oval spreading from Long Island to Ohio, Virginia, and Lake Ontario would be completely annihilated. One-half of the people, one-third of the wealth of the United States would be completely rubbed out. The world's greatest metropolis would lie a smoking ruin, . . . . Only a few broken struts set awry and throwing lengthened shadows across sullen lagoons would survive as reminders of the solid masonry of the city . . . .Many readers of the present article are no doubt wondering why they have never heard of this comet that struck the Carolinas. The answer is scientific controversy - the issue is still "up in the air" so to speak. Melton and Schriever's theory enjoyed about two years of broad acceptance before more "down to earth" explanations started coming forth. None of the terrestrial theories were, until recently, any more testable than the comet strike idea; they were, however, more in line with the picture of a slowly changing Earth, and so were more acceptable to those who favored that view.

Outside this devastated area would be a larger ellipse, one thousand miles across, where compressed air had worked its will. Its force would level every city, every building; its fiery breath would kill every living thing as far west as Minneapolis and Kansas City, and as far south as Jackson, Mississippi, and Montgomery, Alabama.

Even Europe would not escape, for every Atlantic coastal plain would be ravaged by an enormous tidal wave put in motion when the compressed air forced the Atlantic back beyond the continental shelf.

The controversy over the origin of the Carolina Bays is a bit too involved to go into here. Interested readers should pick up a copy of Henry Savage's The Mysterious Carolina Bays (1982) for a full historic account. For the purpose of this article it is enough to say that William Prouty, who spent the most time (sixteen years) actually studying these 'bays,' believed them to be impact structures which were formed at the end of the Pleistocene and prior to at least one rise in sea level. This researcher, who was head of the University of North Carolina geology department, died in 1949 and so had no access to radioactive carbon dating. What is notable is that Prouty's stratigraphically derived date places the formation of these features just prior to the younger dryas cold event which is now well dated. Very little research on the origin of the Carolina Bays has been done since Prouty's death. This should soon change.

The in-process shift of research paradigm away from gradualism has renewed interest in features like the Carolina Bays (the number of identified impact structures has risen by several hundred percent over the past decade). Researchers, though, face quite a project in establishing conclusive evidence of the Carolina Bays being impact structures. There are about half a million of these elliptical formations, and they are found along the Atlantic coast from Maryland down into northern Florida. Their number and wide geographic distribution was often used as an argument against an impact origin. To establish them unequivocally as caused by an impact event, a significant number (at least twenty) of 'bays,' located in disparate regions of their occurrence will need to be excavated. This translates into a fairly hefty grant proposal, particularly when the cost of performing definitive tests on materials recovered during excavations is included. Federally provided research money, with the exception of what goes toward new weapon systems, has not been plentiful of late. This makes it difficult for scientists to take on a project like the Carolina Bays. Perhaps this article will help hasten funding for such an undertaking. The money does not have to come from federally endowed sources. In the opinion of this author it will be money well spent; for, if the Carolina Bays are proven to be impact features which were formed a little over eleven thousand years ago, we will have found "Lucifer's" footprints.

The widespread association of an evil serpent with the loss of a happier time for humanity is not due to coincidence, and if certain aspects of this common myth are due to cultural diffusion, these could have just as easily come from the New World to the Old - possibly by way of the red paint people, a recently discovered coastal culture that flourished around seven thousand years ago. This culture left similar artifacts on both sides of the north Atlantic and so probably told basically the same stories on either shore. The idea that our early ancestors were strictly pedestrian is fast fading. It is now established that humans have been in Australia for over forty thousand years - they did not wade there. This aside, one can see even in the familiar Hebrew version of the expulsion from Eden metaphorical signs of explicable extraterrestrial influence. The "fallen angel," Lucifer, in the guise of a "serpent," causes the "immortal old man in the sky" to become angry with his children (creations in "his" likeness) and punish them by expulsion from their sustaining garden, which "he" then guards with "his flaming sword." Much more telling, however, are the stories which were retained by the people in the New World. These bring forth details not found elsewhere. For example, the Walam Olum, a traditional history of the Leni Lenape (Delaware Indians), provides both pictographic and linguistic features which suggest that the "good ole days" were brought to a close by a celestial, "serpentine," intruder.

The symbols, and accompanying text, shown, are from The Lenape and Their Legends, first published in 1884. Noted ethnologist, Daniel G. Brinton, authored this work which concludes with his new translation of the Walam Olum. Prior to presenting the actual text and symbols, Brinton offers his readers a general synopsis of this valuable native American record:

The myths embodied in the earlier portion of the Walam Olum are perfectly familiar to one acquainted with Algonkin mythology. They are not of foreign origin, but are wholly within the cycle of the most ancient legends of that stock. Although they are not found elsewhere in the precise form here presented, all the figures and all the leading incidents recur in the native tales picked up by the Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century, and by Schoolcraft, McKinney, Tanner and others in later days.

The cosmogony describes the formation of the world by the Great Manito, and its subsequent despoliation by the spirit of the waters, under the form of a serpent. The happy days are depicted, when men lived without wars or sickness, and food was at all times abundant. Evil beings, of mysterious power, introduced cold and war and sickness and premature death. Then began strife and long wanderings.

However similar this general outline may be to European and Oriental myths, it is neither derived originally from them, nor was it acquired later by missionary influence.

Anyone who has witnessed a water snake in pursuit of minnows can not fail to see how metaphorically apt a serpent is to describe a large comet. This author can remember vividly, as a child, chasing such a creature about in a creek with a friend. The snake, totally submerged, looked to us like the granddaddy of tadpoles. Fortunately the serpent caught its fish and surfaced before we could catch the snake. Needless to say, we were somewhat alarmed at having chased this creature for several minutes, for we did more than once, almost catch it.

This ignorance of potential peril we, as children reared in an early fifties suburban environment, almost fell victim to, has much in common with humanity's present slowness in realizing the actual danger Earth-orbit-crossing objects pose. To us, the creek was an extension of our well-manicured yards - a safe place. Similarly, scientists of the mid-nineteenth century managed to convince themselves that the Earth was safe from cosmic serpents. This is well illustrated in a note which appeared in the February 15, 1872 issue of Nature (Vol. 5, p. 310):

We have reason to know that many weak people have been alarmed, and many still weaker people made positively ill, by an announcement which has appeared in almost all the newspapers, to the effect that Prof. Plantamour, of Geneva, has discovered a comet of immense size, which is to "collide," as our American friends would say, with our planet on the 12th of August next. We fear that there is no foundation whatever for the rumour. In the present state of science nothing could be more acceptable than the appearance of a good large comet, and the nearer it comes to us the better, for the spectroscope has a long account to settle with the whole genus, which up to this present time has fairly eluded our grasp. But it is not too much to suppose that the laymen in these matters might imagine that discovery would be too dearly bought by the ruin of our planet. Doubtless, if such ruin were possible, or indeed probable - but let us discuss this point. Kepler, who was wont to say that there are as many comets in the sky as fishes in the ocean, has had his opinion endorsed in later times by Arago, who has estimated the number of these bodies which traverse the solar system as 17,500,000. But what follows from this? Surely that comets are very harmless bodies or the planetary system, the earth included, would have suffered from them long before this, even if we do not admit that the earth is as old as geologists would make it. But this is not all. It is well known that some among their number which have withal put on a very portentious appearance are merely the celestial equivalents of our terrestrial "wind-bags".It is important for the reader to understand that the view expressed above did not vanish due to the work of Barringer and others who found evidence of past impact events. Until recently, only the Carolina Bays presented any serious challenge to the notion of a world that changed very slowly. Small impacts were merely incorporated into this dominant view of our planet's past, their effect on Earth being seen as local and somewhat like a violent volcanic eruption. Confidence that our world's geologic and biologic history could be explained within the confines of presently observed phenomena did not really weaken seriously until the mid-nineteen-sixties. Most damning to this view which had dominated the Earth sciences for over a century was the growing number of asteroidal objects that were found where they should not be. One of these Earth-orbit-crossing objects - Icarus - had researchers quite concerned.

In July of 1966, United Press International (UPI) fed to newspapers around the world this short report:

Sydney, Australia - An Australian scientist says if an asteroid now speeding toward the earth veered just slightly, it would crash into the planet with the impact of 1,000 hydrogen bombs.Butler's suggestion that nuclear tipped rockets could be used to prevent such a collision inspired M.I.T. professor Paul Sandorff to assign, as a hypothetical problem for his systems engineering class, a detailed study of just how to go about this. "Project Icarus," as the study come to be called, drew quite a bit of attention itself. Time magazine ran an article on the endeavor in June of 1967 and the following year the class study was published as a book - Project Icarus - which is unusual for a student project. In this book the reader can find these revealing lines:

Prof. S.T. Butler, professor of theoretical physics as Sydney University, made the statement in an interview with the Sydney Telegraph.

He said the asteroid known as Icarus was speeding toward the earth at 70,000 miles per hour and was expected to pass four million miles away in 1968.

"If Icarus hit the earth, it would be like the explosive power of 1,000 hydrogen bombs," Butler said. He added that four million miles away from the earth was "only a stone's throw for outer space.

Butler said scientists in the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union were closely studying the elliptical orbit of the asteroid. He said it could possibly be destroyed with a high-altitude rocket armed with a nuclear head if it neared the earth.

"It sounds fantastic," Butler said, "but we could land a rocket with pinpoint accuracy 50 million miles away and destroy it. This is where billions spent on space research pays off."

He said the scientists were keeping close tabs on the asteroid.

Butler said scientists feared that if the asteroid altered its course a fraction of a foot, it would come within the earth's gravitational pull.

"The consequences of a collision with Icarus are unimaginable; the repercussions would be felt the world over. In dissipating the energy equivalent of half a trillion tons of T.N.T., 100 million tons of the Earth's crust would be thrust into the atmosphere and would pollute the Earth's environment for years to come. A crater 15 miles in diameter and perhaps 3 to 5 miles deep would mark the impact point, while shock waves, pressure changes, and thermal disturbances would cause earthquakes, hurricanes, and heat waves of incalculable magnitude. Should Icarus plunge into the ocean a thousand miles east of Bermuda for example, the resulting tidal wave, propagating at 400 to 500 miles per hour, would wash away the resort islands, swamp most of Florida, and lash Boston - 1500 miles away - with a 200-foot wall of water".The words ". . . threatened by what had so recently been considered a folly" are most indicative of the alteration in world view taking place in this decade of change. Gradualism was doomed - the writing was on the wall. A little over a decade later hard evidence extracted from clay covering the dinosaurs would be on the table. Interestingly the 1979 discovery of the now famous iridium anomaly by the Alvarez team coincides with the Hollywood release of the movie Meteor, in which Earth is saved from a five-mile-across meteoroid by the combined strength of U.S. and Soviet nuclear forces. The film was inspired by "Project Icarus."

"In light of the consequences of a collision with an asteroid the size of Icarus, the possibility of such a collision, no matter how remote, cannot go unrecognized. The world must be prepared, at least with a plan of action, in case it should suddenly find itself threatened by what had so recently been considered a folly".

Quite a few long standing misconceptions fell by the wayside as humanity entered the "space age." New information led to new ideas. This cascade of novel input tended to liberalize academia. Students felt free to "grill" their professors on why certain views were accepted. As a result, conclusions arrived at by earlier researchers fell under closer scrutiny.

From the standpoint of this article one of the most important notions to go by the wayside was the idea that primitive people were less intelligent than we moderns. This view of "uncivilized" people was given scientific credence by Charles Darwin who predicted that, upon acceptance of his theory of evolution through natural selection, "Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation." The idea that our distant ancestors as well as contemporary "primitive" people were less mentally evolved influenced anthropological thought beyond the middle of this century. This notion of gradual mental evolution was finally put to test by the extensive field work of French social anthropologist Claude Levi Strauss who contended:

A primitive people is not a backward or retarded people; indeed it may possess a genius for invention or action that leaves the achievements of civilized peoples far behind.Many of the books this researcher had penned were made available to English speaking people in the sixties. His works were very influential during this intense period of social change.

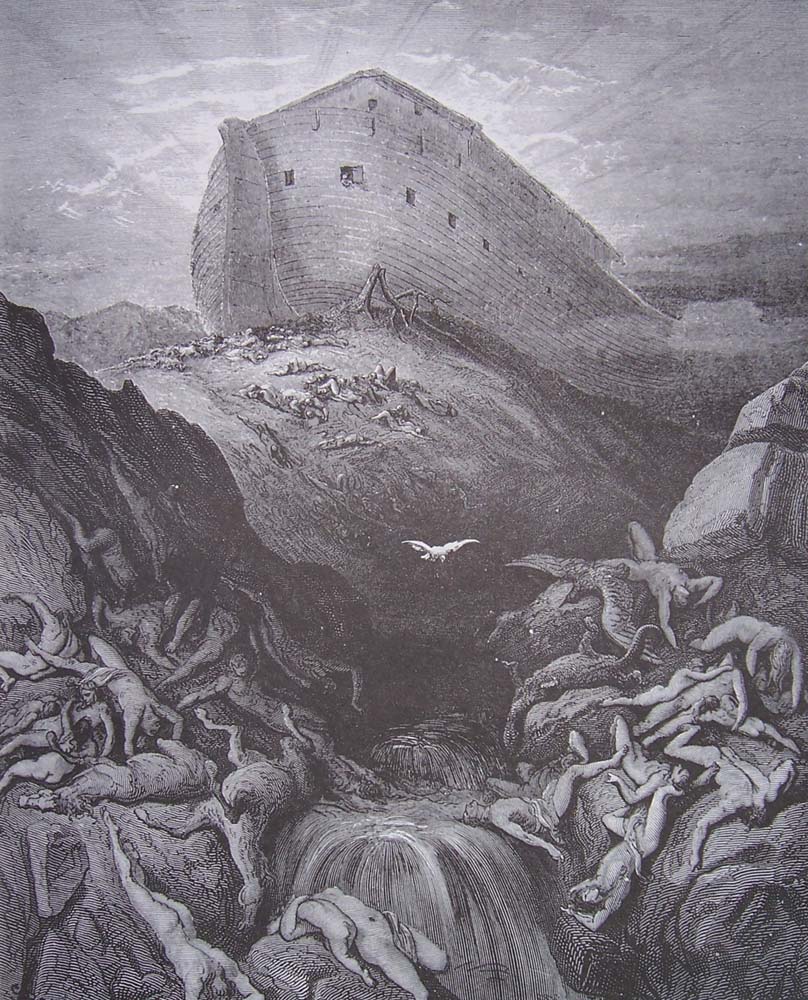

With this egalitarian view of our prehistoric ancestors, anthropologists are now much less apt to make hasty, condescending judgments about why certain handed down traditions came about. Legends of great floods are no longer simply dismissed as watered up versions of an unusually bad conventional flood. However, the realization that many such stories were not just exaggerations is not based exclusively on a greater appreciation of our early ancestors' ability to discriminate between a bad flood and a DELUGE.

Part D

Uniformitarianism succeeded in displacing catastrophism as the acceptable approach to unraveling Earth's past, largely because slow moving glaciers better explained the presence of displaced boulders. Catastrophists had surmised that these large rocks were washed to where they were found during a great flood which, they believed, was brought about by the close approach or impact of a comet. Though this is a vast over simplification of the contest which took place between these two schools of thought, it serves to show why true blue uniformists have had trouble accepting evidence of catastrophic floods or impacts. A pertinent example of what happens when scientists reject a hypothesis on the basis of prior assumption rather than evidence is provided by the Spokane flood controversy--a debate which closely parallels the controversy over the origin of the Carolina Bays.

Geologist J. Harlen Bretz began his study of the peculiar geomorphic features found on the Columbia Plateau of eastern Washington in the summer of 1922. By 1932 he had become a "heretic" in the minds of many fellow geologists, for Bretz contended that the features which he called, collectively, the Channeled Scabland, were created by catastrophic floods. Judging his research completed, Bretz simply stepped out of the controversy his decade of work engendered and went on to other problems, advising his colleagues that only field evidence could, or should, decide the issue.

Bretz was more fortunate than most researchers who have posited an unpopular hypothesis; he lived long enough to see his view accepted. One can imagine the smile that came to Bretz's face, when, in 1965, this wise octogenarian received a lengthy telegram from an international team of geologists which began with "greetings and salutations" and ended with: "We are now all catastrophists."

Victor R. Baker provides an excellent overview of this long, drawn-out debate in his article, "The Spokane Flood Controversy and the Martian Outflow Channels," published in Science (Vol. 202, 22 Dec. 1978). Baker points out the similarity of features revealed on Mars by space-faring cameras and the Channeled Scabland, however, most of his paper focuses on the Spokane flood controversy. He ends the article with these words:

The Spokane flood controversy is both a story of ironies and a marvelous exposition of the scientific method. One cannot but be amazed at the efforts made to give a uniformitarian explanation for the Channeled Scabland and to uphold the framework of geology as it had been established in the writings of Hutton, Lyell, and Agassiz. The final irony may be that Bretz's critics did not appreciate the scientific implications of Agassiz's famous dictum, "study nature, not books." Perhaps no geologist has understood and lived the spirit of those words more enthusiastically than J. Harlen Bretz.It is difficult to envision the great flood, or floods Bretz's research revealed. In some areas evidence indicates the surface of the water was over six hundred feet above ground level! One aqueous mountain was so vast that it manifested a surface gradient steep enough to push water, in surrounding river valleys, upstream more than seventy miles. Abrupt breaks in the icy confines of glacial Lake Missoula apparently caused this flooding. Exactly why this lake so suddenly lost its integrity is still open to debate. It is also yet unclear how many catastrophic floods occurred.

The last major deluge in this area took place over eleven thousand years ago; volcanic tephra from a dated eruption of Glacier Peak establishes this. Given the proven antiquity of this flooding episode, one can but marvel at the lucid, and if anything, understated account passed along to us by Chief Lot, a respected leader in the Spokane Indian community:

A long time ago the country around where Spokane Falls are now, and for many days' journey east of it, was a large and beautiful lake. In the lake were many islands, and on its shores were many villages with many people. The Indians were well fed and happy, for there were plenty of fish in the lake and plenty of deer and elk in the country around it.This legend was read by Major R.D. Gwydin at a meeting of the Spokane Historical Society, which was held toward the end of the last century--long before Bretz began his investigation. The full value of this account could not have been apparent then. Only results of recent geologic field work can provide the story with a time frame and so gauge its accuracy.

But one summer morning the people were startled by a rumbling and a shaking of the earth. The waters of the lake rose. Soon the waves became mountains of water that broke with fury against the shore.

Then the sun was blotted out, and darkness covered the land and the water. Terrified, the people ran to the hills to get away from the pounding water. For two days the earth rumbled and quaked. Than a rain of ashes began to fall. It fell for several weeks.

At last the ashes stopped falling, the waters of the lake became quiet, and the Indians came down from the hills. But soon the lake began to disappear. Dry land rose where the water had been. Many people died, for there was nothing to eat. The game animals had run away when the people fled to the hills, and no one dared go out on the lake to fish.

Some of the water was flowing westward from the lake that remained. The people followed it until they came to a waterfall. Soon they saw salmon coming up the new river from the big river west of them. So they built a village beside the waterfall in the new river and made it their home.

The fact that the legend tells of a great lake in the Spokane area which was badly drained via a new river created by the action of a catastrophic flood that occurred in conjunction with violent tectonic activity, including vulcanism, makes it difficult to misplace in time. This is almost certainly an eleven thousand year old eyewitness account of a, or the, Spokane flooding episode. Not only does this succinct report tell of a feature which required years of geologic field work to establish--the presence of a vast lake in the Spokane area--but it also reveals a detail which could not be easily proven by a contemporary geologic investigation. The assertion in the legend, that volcanic ash fell during this flood should be considered a valuable piece of collateral evidence which could shed further light on events of this time period. To date, geologists have only used the tephra deposited on these flood features as a means of limiting the time interval in which the flooding could have occurred. Accepting this Native American legend as a likely eyewitness account, rather than an ex-post-facto construct, might allow geologists to affix a fairly firm date to at least one major Spokane flood.

Folklore, like any large collection of literature (including scientific works) accumulated over time, contains valid observations along with suppositions. Generally, it is not difficult to recognize hypothesis in handed down tales, for early expositors' rationalizations were often quite fanciful. The remains of giant herbivores inspired a variety of tales which sought to explain their presence. These stories varied from culture to culture, however, almost all have one thing in common; the given explanation is totally implausible and obviously an ex-post-facto fabrication.

J.P. MacLean provides an overview of notions engendered by finds of giant bones in his Mastodon, Mammoth and Man published in 1878:

The fossil bones of the elephant family when first discovered were ascribed either to human beings or else the demi-gods. The patella of a fossil elephant found in Greece was taken for the knee-bone of Ajax; the remains, thirteen feet in length, discovered by the Spartans at Tegea, were assigned to the body of Orestes; those, eighteen feet in length, discovered in the Isle of Ladea, were assigned to Asterious, son of Ajax; the bones discovered in the fourth century at Trapani, in Sicily, were ascribed to the pretended body of Polyphemus. So numerous were the discoveries, and so universally regarded to be those of human beings, that the literature of the middle ages, on this subject, is quite voluminous, and has been entitled "Gigantology."An interesting correlation on the Spanish belief, just mentioned comes from the "Terminal Essay" of Richard F. Burton's famous Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, published in 1886:

In 1456, in France, bones of pretended giants were noticed in the bed of the Rhone. Soon after other discoveries were made near Saint-Peirat, opposite Valence, which were cared for by the Dauphin, afterwards Louis XI, and sent to Bourges, where they long remained objects of curiosity in the interior of the Saint-Chapelle. In the same neighborhood, in 1564, two peasants noticed, on the banks of the Rhone, some great bones sticking out of the ground. Cassanion pronounced them giants' bones, and this discovery doubtless caused him to write his treatise entitled "De Gigantibus."

In the Canton of Lucerne, Switzerland, in the year 1577, a storm uprooted an oak near the cloisters of Reyden, exposing some large bones. These bones were examined by Felix Platen, then a celebrated physician and professor at Basle, who declared them to be the remains of a giant nineteen feet in height. On account of the conclusions of Platen the inhabitants of Lucerne adopted the image of the fabulous giant as the supporter of the city arms.

Otto de Guericke, a celebrated physicist and inventor of the air pump, in 1663, witnessed the discovery of the bones of the elephant, along with its enormous tusks, buried in the shelly-limestone, Germany. The tusks were taken for horns, and out of the remains Leibnitz constructed a strange animal, carrying a horn in the middle of its forehead, and in each jaw a dozen molar-teeth a foot long, and calling the creature the fossil unicorn. In his "Protogaea" he gave a description and a drawing of the imaginary animal. For more than thirty years the unicorn of Leibnitz was universally accepted throughout Germany, . . .

The gigantic bones discovered in 1705, thirty miles south of Albany, New York, were regarded as additional proof of the ancient stories relative to the past existence of a race of giants. One of the teeth was shown to Governor Dudley, of Massachusetts, who was "perfectly of opinion that the tooth will agree only to a human body, for whom the flood only could prepare a funeral; and without doubt he waded as long as he could keep his head above the clouds, but must, at length, be confounded with all other creatures." The bones of the mastodon found near Santa Fe de Bogota, in the "Field of Giants," were formerly taken for human remains. And, in like manner, the great quantity of bones of this animal found in the Cordilleras originated the Spanish tradition that Peru was formerly inhabited by men of colossal stature.

. . . Speaking of the arrival of the Giants at Point Santa Elena, [Peru] Cieza says, they were detested by the natives, because in using their women they killed them, and their men also in another way. All the natives declare that God brought upon them a punishment proportioned to the enormity of their offence. When they were engaged together in their accursed intercourse, a fearful and terrible fire came down from Heaven with a great noise, out of the midst of which there issued a shining Angel with a glittering sword, wherewith at one blow they were all killed and the fire consumed them. There remained a few bones and skulls which God allowed to bide unconsumed by the fire, as a memorial of this punishment.Burton recognized this as a likely " . . . Europeo-American version of the Sodom legend." As the reader will soon see the American component of this tale could be much more ancient than the legend of Sodom and Gomorrah. In the above story, two disparate legends, each likely inspired by an actual impact event, though probably not the same one, have been merged to form a totally erroneous tale.

Thomas Jefferson was also intrigued by these commonly found large bones. By his time most well-informed people knew these to be the remains of large elephants; the question in Jefferson's mind was: Were some still lurking about? In his Notes on Virginia, first published in 1787, Jefferson reports:

Our quadrupeds have been mostly described by Linnaeus and Mons. de Buffon. Of these the mammoth, or big buffalo, as called by the Indians, must certainly have been the largest. Their tradition is, that he was carnivorous, and still exists in the northern parts of America. A delegation of warriors from the Delaware tribe having visited the Governor of Virginia, during the revolution, on matters of business, after these had been discussed and settled in council, the Governor asked them some questions relative to their country, and among others, what they knew or had heard of the animal whose bones were found at the Saltlicks on the Ohio. Their chief speaker immediately put himself into an attitude of oratory, and with a pomp suited to what he conceived the elevation of his subject, informed him that it was a tradition handed down from their fathers, "That in ancient times a herd of these tremendous animals came to the Big-bone licks, and began a universal destruction of the bear, deer, elks, buffaloes, and other animals which had been created for the use of the Indians; that the Great Man above, looking down and seeing this, was so enraged that he seized his lightning, descended on the earth, seated himself on a neighboring mountain, on a rock of which his seat and the print of his feet are still to be seen, and hurled his bolts among them till the whole were slaughtered, except the big bull, who presenting his forehead to the shafts, shook them off as they fell; but missing one at length, it wounded him in the side; whereon, springing round, he bounded over the Ohio, over the Wabash, the Illinois, and finally over the great lakes, where he is living at this day."Jefferson included this native narrative because it lent support to the idea that these large animals were still extant; he did not accept the notion of total extinction. This is made plain later in the same work, where, referring to his list of quadrupeds common to Europe and America, Jefferson states:

. . . It may be asked, why I insert the mammoth, as if it still existed? I ask in return, why I should omit it, as if it did not exist? Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced, of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken. To add to this, the traditionary testimony of the Indians, that this animal still exists in the northern and western parts of America, would be adding the light of a taper to that of the meridian sun. Those parts still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored and undisturbed by us, or by others for us. He may as well exist there now, as he did formerly where we find his bones.Jefferson supposed that these large animals, probably carnivorous, had recently abandoned eastern American due to a general depletion of wild game, which, in turn, he felt, was caused by the enhanced hunting capability of natives armed with European weapons.

Obviously, this early champion of freedom saw the 'stormy' part of this native legend as nothing more than flamboyant free verse, added to spice up the story. Recall that, when Jefferson wrote his Notes on Virginia, well-informed individuals 'knew' that rocks could not fall from the sky. The mention of a "Great Man above" hurling 'bolts' at the long-nosed beasts from a mountain top probably caused a chuckle to issue from the great statesman as he first took this legend in - "How Jovian!" - he likely thought. Jefferson would have never imagined that this part of the story could have any historic value, however, it most probably does.

The reader can most clearly appreciate a likely connection between this legend and the formation of the Carolina Bays by comparing the geographic location given in the fullest version of this story with a map showing the probable 'footprint' of the suspected impact event. This particular rendering of the tale was provided, sans translator, by an English speaking member of the Delaware tribe around the turn of the century:

Long ago, in time almost forgotten, when the Indians and the Great Spirit knew each other better, when the Great Spirit would appear and talk with the wise men of the Nation, and they would counsel with the people; when every warrior understood the art of nature, and the Great Spirit was pleased with his children; long before the white man came and the Indians turned their ear to the white man's God; when every warrior believed that bravery, truth, honesty, and charity were the virtues necessary to take him to the happy hunting-grounds; when the Indians were obedient and the Great Spirit was interested in their welfare there were mighty beasts that roamed the forests and plains.Though the geographic correlation suggests that this legend is rooted in fact, it would not be possible to rule out a coincidentally fortuitous ex-post-facto origin for this story without additional evidence. Amazingly there is a rock hard exhibit which may rule this possibility out.

The Yah Qua Whee or mastodon that was placed here for the benefit of the Indians was intended as a beast of burden and to make itself generally useful to the Indians. This beast rebelled. It was fierce, powerful and invincible, its skin being so strong and hard that the sharpest spears and arrows could scarcely penetrate it. It made war against all other animals that dwelt in the woods and on the plains which the Great Spirit had created to be used as meat for his children--the Indians.

A final battle was fought and all the beasts of the plains and forests arrayed themselves against the mastodon. The Indians were also to take part in this decisive battle if necessary, as the Great Spirit had told them they must annihilate the mastodon.

The great bear was there and was wounded in the battle.

The battle took place in the Ohio Valley, west of the Alleghanies. The Great Spirit descended and sat on a rock on the top of the Alleghanies to watch the tide of battle. Great numbers of mastodons came, and still greater numbers of the other animals.

The slaughter was terrific. The mastodons were being victorious until at last the valleys ran in blood. The battlefield became a great mire, and many of the mastodons, by their weight, sank in the mire and were drowned.

The Great Spirit became angry at the mastodon and from the top of the mountain hurled bolts of lightning at their sides until he killed them all except one large bull, who cast aside the bolts of lightning with his tusks and defied everything, killing many of the other animals in his rage until at last he was wounded. Then he bounded across the Ohio river over the Mississippi, swam the Great Lakes, and went to the far north where he lives to this day.

Traces of that battle may yet be seen. The marshes and mires are still there, and in them the bones of the mastodon still are found as well as the bones of many other animals.

There was a terrible loss of the animals that were made for food for the Indians in that battle, and the Indians grieved much to see it so the Great Spirit caused in remembrance of that day, the cranberry to come and grow in the marshes to be used as food, its coat always bathed in blood, in remembrance of that awful battle.

Part E

Short of a full contemporary investigation of the Carolina Bays, the strongest physical evidence that seems to link the mega-fauna extinction with an extraterrestrial event is in the form of an artifact known as the Lenape Stone.

The largest piece of this gorget was discovered in 1872 by Barnard Hansell while plowing on his father's farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. After carrying the stone in his pocket for a few days, young Hansell put it in a tobacco box with other Indian relics he had found and there it stayed until the spring of 1881 when he sold it along with about 200 arrowheads and other artifacts for the sum of two dollars and fifty cents to Henry D. Paxon, the son of the local justice of the peace, Albert Paxon. The nineteen-year-old collector (Paxon) asked Hansell about the missing piece of stone and indicated that he would like to have it should it turn up. This prompted Hansell to be on the look-out for the other piece which he found while harvesting corn in the fall of the same year. Hansell gave the smaller piece of the Lenape Stone to young Paxon free of charge on the ninth day of November, 1881, while visiting the Paxon's home for the purpose of paying his (Hansell's) taxes.

This carved gorget soon attracted academic interest and became the subject of a small book published in 1885. The author of The Lenape Stone, H.C. Mercer, was very much aware of fraudulent Indian relics that were becoming all too common during this time period and so spent a great deal of time and effort to establish the authenticity of this find. During the course of his investigation, which included an excavation on the Hansell property, three other carved gorgets were found on this farm. Mercer felt very sure that this stone was a real artifact of the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) Indians known to have lived in this region. To date, nothing has been found to contra-indicate Mercer's assessment of this gorget.

Most impressive to Mercer was the correlation between the images on the stone and the legend Jefferson had recorded. After quoting this story from Jefferson's Notes on Virginia, Mercer conveys to his readers that:

Making due allowance for translation, and a reasonable amount of garbling, the points of similarity between the carving and the tradition--the great man above (the sun) looking down, the lightning, and the big bull presenting his forehead to the shafts, and at length wounded in the side--are very striking; and if we compare the curious circle enclosing a dot, on the inclined foreground to the right, with the "neighboring mountain," and the footprint on the rock of the tradition, the correspondence seems again too unusual for mere coincidence. On the other hand, the tradition says nothing of warriors or wigwams, or of planets, moon, and stars, yet these differences may naturally be accounted for if we suppose the stone older than the tradition, and that in the latter the local and matter- of-fact elements of time, place, and human agency would have been the first to fade away as time went on. But this is not the only Indian tradition of a great monster --presumably the mammoth--which has been preserved to us.Clearly, as Mercer asserted in his book, this gorget served as a mnemonic devise. Whether this particular artifact was carved in final days of the large herbivores or produced later from images on a prior story telling aide, the likeness of a large elephant is very strong evidence that the legend of Yah Qua Whee was born over ten thousand years ago.