We are encouraged that the Senator has entered the dialog of how we can improve our food system and the public's health. However, many of the criticisms of Walsh's article presented in the statement are unfounded and serve to misinform consumers.

The Senator covers a wide variety of topics in his statement, we have selected a handful of issues raised in quotes from the Senator's statement to address what we believe consumers would benefit from having clarified. Specifically, we will comment on the Senator's claims regarding the Danish ban on antimicrobial growth promoters, the contribution of industrial animal production to water quality, organic production methods and consumer demands.

"We only have to turn to our neighbors across the Atlantic to see how a ban on antibiotics has played out. The European Union made a decision to phase out the use of antibiotics as growth promoters over 15 years ago and in 1998 Denmark instituted a full voluntary ban which in 2000 became mandatory. [T]he science does not back that positive improvements in public health has occurred due to the Denmark ban"Antimicrobial drugs, many of which are the same as those used in human medicine, are routinely added at subtherapeutic doses to animal feed for the purpose of growth promotion. A great deal of evidence has been amassed linking this practice to the development of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria (Silbergeld et al 2008); infections with these resistant bacteria in humans are extremely difficult to treat, as they are less (if at all) responsive to antibiotics.

Contrary to Senator Grassley's claims (some of which follow in quotes), Denmark has largely benefited from banning antibiotics as growth promoters. Last week, Congresswoman Louise Slaughter (D-NY) released a letter from Frank M. Aarestrup of the Danish Technical Institute (DTI) detailing the Danish experience with elimination of non-therapeutic antimicrobials. This letter, and a recent commentary from Aarestrup and Pires (2009), address and contradict a number of assertions made in Senator Grassley's letter.

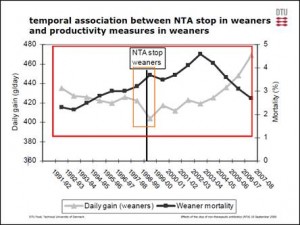

"After the ban was implemented in 1999, pork producers saw an immediate increase in piglet mortality and post-weaning diarrhea."Evidence presented by the DTI refutes this point, indicating that weaner mortality (or death of pigs who are no longer nursing) initially continued to increase at a rate consistent with trends before the ban, though weaner mortality "has improved considerably in recent years" to levels below those prior to the year of the ban, as of 2007-8 (see FIGURE from Håkan Vigre of the DTI).

"I think an interesting statistic is that in 2009 the use of therapeutic antibiotics in Danish pigs is greater than what was used to prevent disease and promote growth prior to the ban in 1999."Senator Grassley's statement is wrong and inconsistent with evidence from the DTI, which has reported that total antimicrobial consumption in Danish food animal production has been reduced by 51% between 1992 and 2008. It is also noted that in countries where existing usage is higher (including the United States), that the overall reduction in antimicrobial use would also likely be higher - the authors approximate an 80% reduction in the US.

"In fact, the World Health Organization in 2002 released a study on antimicrobial resistance and could find no public health benefit from the Denmark ban."Contrary to Senator Grassley's claim, the Danish Technical Institute reported "major reductions" in antibiotic-resistant pathogens, indicator bacteria and zoonotic bacteria. Decreased presence of these pathogens will likely reduce opportunities for human contact with multidrug-resistant bugs and development antibiotic-resistant infections.

"If this ban had resulted in improvements to public health, suffering consequences like piglet mortality would make sense, but the science does not back that positive improvements in public health has occurred due to the Denmark ban."Senator Grassley fails to note that many of the animal health consequences that occurred after the antimicrobial ban was implemented were transient, and that conditions improved shortly after. Håkan Vigre of the DTI reports improvements in both the Danish swine and poultry industries after the ban. Of special note are the aforementioned long-term reduction in piglet mortality, and improvements in both weaner and finisher average daily weight gain.

Similar improvements have been seen in the broiler chicken industry, with a nearly 1% increase in broiler feed conversion ratio and reduction in dead broilers observed after the implementation of the ban. Also noteworthy is a 2008 economic analysis by Lawson et al. [PDF] of the Danish antimicrobial ban on the poultry industry, which indicated that the ban had no net economic effect on Danish poultry producers.

In summary, it is apparent that the Danish experience is indicative of benefits to human health and animal health at little to no expense to food animal producers.

"We know that hypoxia is partly a natural phenomenon, but scientists generally agree that nitrates from agriculture and other man-made factors contribute to it... Technology has allowed farmers to apply the exact amount of fertilizer in the right way so there isn't excess..."Senator Grassley rightly attributes hypoxia to anthropogenic influences - since the explosive growth in synthetic fertilizer use in the 1960s, the number of dead zones has roughly doubled each decade (Diaz and Rosenberg 2008), and human contributions to nitrogen pollution now equal - if not exceed - land-based contributions from natural processes (Howarth 2008).

However, while nutrient management practices are essential in reducing nutrient runoff and volatilization of ammonia and nitrous oxide into the atmosphere, Senator Grassley's assertion that these methods completely prevent excess runoff is unsupported. Further, his statement implies that such practices have been universally adopted by the agricultural industry, an unlikely scenario given the recent dominance of agriculture in contributing to nutrient pollution (Howarth et al. 2002) and the estimated 20% of fertilizer nitrogen applied to U.S. crops that reaches ground and surface waters (Howarth et al. 1996).

"...even organic farming (which [Brian Walsh, author of the original Times article] seems to hold in high esteem) uses manure for fertilizer which contains nitrogen."For industrial-sized operations, it is the magnitude, concentration and localization of animal waste that poses a risk to surface and ground waters as a result of runoff and leaching (Mallin and Cahoon 2003) - this effect is a function of operation size and remains a concern regardless of whether or not an operation is organic.

What Senator Grassley does not acknowledge is that feed used in conventional (non-organic) animal production methods (Sapkota et al. 2007) results in the presence of additional contamination of waste, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria and other pathogens, synthetic hormones and heavy metals such as arsenic, all of which constitute serious environmental and public health concerns (Nachman et al. 2005, Silbergeld et al. 2008, Khan et al. 2008).

"While less than 1 percent of agriculture is farmed organically as he points out, a simple economics lesson would tell us that supply and demand are in direct relationship to one another."Senator Grassley's statement suggests that the small percentage of cropland devoted to organic agriculture reflects the level of consumer demand for organic foods. The senator's comment is shortsighted - a snapshot of the current levels of organic production does not necessarily correlate with actual demand, nor does it convey the rapidly growing nature of the market.

Research has documented the rapidly increasing production of and demand for organic foods. For example, USDA estimates demonstrate that cropland used for agricultural produce doubled between 1992 and 1997, and that preliminary data would suggest that this increase continued between 1997 and 2001 (Dimitri and Greene 2007).

Further, a USDA report released just this month demonstrated that the public wants organic food and that the demand currently outpaces the supply (Dimitri and Oberholtzer 2009, Kim 2009). Also noteworthy is that this interest in organic food isn't limited to those with abundant resources - some evidence suggests that low income and minority populations share an interest in foods produced with fewer chemicals, which may be supported by the finding that household income is not positively associated with expenditures on organic produce (Stevens-Garmon et al. 2007).

Despite the existing demand, more sustainably produced foods are often more expensive than their conventionally produced counterparts for a variety of reasons. These factors, such as relatively higher production costs, lack of a centralized distribution infrastructure, sparse government support, and fewer economies of scale, lead to higher prices on market shelves (Dimitri and Oberholtzer 2009, Neff et al. from Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, in press). Even with these financial hurdles, it has been demonstrated that there exists a willingness to pay among consumers for organically-produced foods (Batte et al. 2007).

"Growing all of our food organically will take more land..."There is no consensus among studies on the relative yields per area of organic versus conventional agriculture. Research has indicated higher yields from organic crops during drought (Pimentel et al. 2005) - a condition that farmers may increasingly need to adapt to, given the pending effects of global climate change. But regardless, yields are far less of an issue to solving world hunger than the inequitable distribution of healthy food - a problem exacerbated by the effects of the current industrial food system.

"And just in the last 10 years have we seen the increased use of biotechnology which has provided yields of over 150 bushels per acre. The author clearly views biotechnology as a bad thing, when in fact traits such as drought resistance and nutrient use efficiency is actually improving corn's performance with less inputs. Many of our technology companies are expecting their yield trends to exceed 300 bushels per acre in the coming years..."Laboratory-engineered "transgenic" crops have fallen woefully short of industry promises. According to a recent report by the Union of Concerned Scientists, traditional breeding techniques have outperformed laboratory-engineered "transgenic" methods in increasing crop yields, while the environmental and health effects of foods that could not otherwise occur in nature remains to be seen (Gurian-Sherman 2009). Further, transgenic crops are genetic clones - and as evidenced by the Irish potato famine, monocrops are not only harmful for biodiversity but are more susceptible to crop disease and pests.

"Our consumers have demanded an affordable food supply and the agricultural industry has answered that call."What isn't captured in Senator Grassley's characterization of the food supply as "affordable" and "reasonably priced" are the associated externalities, or economic, environmental and public health burdens borne by society as a whole. While these impacts are challenging to quantify, one pair of researchers estimated the true cost of these externalities (covering impacts to water, soil, air, wildlife and human health) to be between $6 and $17 billion per year (Tegtmeier and Duffy 2004).

What's more, many of these burdens, especially those related to health and environmental quality, are unevenly distributed across society, with the brunt of the impact being felt by persons living in rural communities surrounding production areas, a disproportionate share of whom are low income and non-white. (Mirabelli et al. 2006, Donham et al. 2007).

Not only that, but the conventional production model cannot last. Conventional agriculture exacerbates climate change, water scarcity, soil degradation, and peak oil - and these resource crises will in turn take an increasingly serious toll on the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of conventional production models. Protection of farmer livelihood, food supply, and food affordability are all at risk without increased attention to sustainable, resilient alternatives.

Additionally, the relatively low costs in the conventional food supply should be recognized as artificially low, bolstered by a set of farm policies that enable those products to be sold below the cost of production.

For example, Tufts University investigators have determined that corn and soybeans, primary staples of animal feed, were sold at prices significantly below market value between 1997 and 2005, and that tax-funded subsidies made up the difference - essentially affording the poultry industry approximately $1.25 billion per year in savings, with American taxpayers picking up the tab (Starmer et al. 2006).

On a truly level playing field, the price gap between conventionally and sustainably produced food would likely be considerably reduced. So while it may seem like our relatively low grocery bills are a dream come true, American tax dollars and medical bills play a key role in artificially driving down our costs at the supermarket.

In summary, we are pleased that Bryan Walsh's article in Time Magazine once again highlighted numerous recognized opportunities for a path towards improvement of our nation's food system. While Senator Grassley's floor statement contained inaccuracies and misinterpretations of available evidence, we are happy for the opportunity to engage in discussion and communicate the findings of rigorously conducted public health, environmental and agricultural research.

About the authors

Keeve Nachman, PhD, MHS, is Science Director for Food Production, Health and Environment at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. His research focuses on determining the environmental, public health and social consequences of industrial food animal production and animal waste management.

Brent Kim, MHS, is a Senior Research Assistant at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. His responsibilities include managing the Community Supported Agriculture Project, assisting with the Agriculture and Public Health Gateway, researching the life cycle impacts of food production and developing interactive online learning tools.

Roni Neff, PhD, MS, is Research and Policy Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future and is on faculty at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her current research addresses themes including: food system contributions to climate change; the food price crisis; the Farm Bill and public health; and access to healthy, sustainably produced food in Baltimore.

Amy Peterson, DVM, is a member of Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future's 2008-09 CLF Predoctoral Fellows. Her work includes investigating the transmission and transfer of antimicrobial resistant bacteria and resistance genes from swine farms to an estuarine environment, affecting both human populations who use the area for fishing and recreation and resident wildlife populations.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter