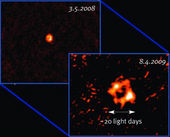

The discovery was serendipitous - the team was studying proper motions in M82 and M81 using the Very Large Array of radio telescopes in New Mexico. On reducing their data, the team (led by Andreas Brunthaler of the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy) noticed a strong new point source of radio emission near the center of M82 - a smallish, irregular galaxy 12 million light-years away with vigorous star formation happening in its middle.

"Most supernovae you only see in the optical," says co-author Geoffrey Bower (University of California, Berkeley). He says this one went unseen because the star was hidden by particularly dense gas and dust. But Stefan Immler (NASA/Goddard) stresses that it would take an enormous amount of material to hide the accompanying ultraviolet and X-ray emissions as well: "There are many other X-ray sources in the bulge of M82, and these are not absorbed." Christopher Stockdale (Marquette University) says: "If nothing else, it clearly shows it's an unusual object."

You can't blame other researchers for being slightly skeptical: they haven't had a chance to check all the UV, X-ray and visible observations that failed to see anything throughout 2008. Even Bower admits, "It's quite striking that a supernova so nearby is completely obscured in the visible."

Brunthaler and collaborators see the radio source expanding, balloon-like, at the speed expected for the shock wave of a supernova: thousands of kilometers per second, a few percent of the speed of light. The radio waves are synchrotron radiation from electrons in the former star's stellar wind as they get swept up by the expanding blast wave. For this to happen, the star must have blown off a massive wind in the millennia before exploding. The ultraviolet flash of the explosion ionized this material, breaking apart its hydrogen atoms into a plasma of protons and electrons - and these emit the radio as the shock wave hits them and plows them forward.

Such strong stellar winds aren't seen in the famous Type Ia supernovae used as cosmic standard candles. These blow up when a white dwarf star accretes enough mass to ignite a nuclear reaction that suddenly consumes it. So the aftermath of that kind of explosion should be radio-weak. Strong radio emission is a sign that the blast was caused by the other mechanism for supernovae: the collapse of a large, massive star's core when it has exhausted all its nuclear fuel. Such stars sometimes emit very thick winds.

The shock wave will thus play back for us a record of the last epoch of the star's history - in reverse order, and at a thousand times the original speed. As the thousand-times-faster shock wave overtakes the wind plasma, it will emit more or less strongly depending on the plasma's local density. By watching for such variations in the coming years, Bower hopes to see signs of what the star went through during its final millennia.

Here is the team's discovery announcement.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter