An asteroid that had initially been deemed harmless has turned out to have a slim chance of hitting Earth in 160 years. While that might seem a distant threat, there's far less time available to deflect it off course.

Asteroid 1999 RQ36 was discovered a decade ago, but it was not considered particularly worrisome since it has no chance of striking Earth in the next 100 years - the time frame astronomers routinely use to assess potential threats.

Now, new calculations show a 1 in 1400 chance that it will strike Earth between 2169 and 2199, according to Andrea Milani of the University of Pisa in Italy and colleagues.

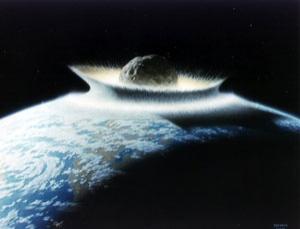

With an estimated diameter of 560 metres, 1999 RQ36 is more than twice the size of the better-known asteroid Apophis, which has a 1 in 45,000 chance of hitting Earth in 2036 (New Scientist, 12 July 2008, p 12). Both are large enough to unleash devastating tsunamis if they were to smash into the ocean.

Although 1999 RQ36's potential collision is late in the next century, the window of opportunity to deflect it comes much sooner, prior to a series of close approaches to Earth that the asteroid will make between 2060 and 2080.

Asteroid trajectories are bent by Earth's gravity during such near misses, and the amount of bending is highly dependent on how close they get to Earth. A small nudge made ahead of a fly-by will get amplified into a large change in trajectory afterward. In the case of 1999 RQ36, a deflection of less than 1 kilometre would be enough to eliminate any chance of collision in the next century.

But after 2080, the asteroid does not come as close to Earth before the potential impact, so any mission to deflect it would have to nudge the asteroid off course by several tens of kilometres - a much more difficult and expensive proposition.

"That's worth thinking about," says Clark Chapman of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

As is often the case, more precise calculations enabled by future observations will most likely rule out a collision. But Milani's team says that routine monitoring of asteroids should be extended to look for potential impacts beyond the 100-year time frame, to identify any other similar cases.

Comment: More likely the earth will be hit by a comet or cometary debris. For a more in-depth look, read Laura Knight-Jadczyk's Forget About Global Warming: We're One Step From Extinction! or Tunguska, the Horns of the Moon and Evolution.