© NASA

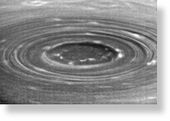

Saturn boasts cyclones at each of its poles that dramatically outpower Earth-roving hurricanes, new images reveal.

The Cassini spacecraft - a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency - recently peered below what had previously appeared to be isolated cumulus clouds at the planet's south pole.

"What looked like puffy clouds in lower resolution images are turning out to be deep convective structures seen through the atmospheric haze," Cassini imaging team member Tony Del Genio said in a press release.

"One of them has punched through to a higher altitude and created its own little vortex."

"Little" is relative - the eye of the storm is surrounded by an outer ring of clouds that measures 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) wide. That's about five times the size of the largest cyclones, or hurricanes, on Earth.

In addition, the Cassini craft found a never-before-seen cyclone at Saturn's north pole. This storm is visible only in near-infrared wavelengths, because the north is too dark right now for visible-light cameras.

Time-lapse movies show the whirlpool-like cyclone at the north pole is rotating at 325 miles (530 kilometers) an hour - more than twice the speed of Earth's fastest hurricanes.

On Earth, powerful storms are driven by warm surface temperatures, which allow moist air from the oceans to rise and condense.

But without large bodies of liquid water, Saturn's polar cyclones are likely fed by heat from thunderstorms deep in its ammonia-filled atmosphere, said Kevin Baines, a Cassini scientist on the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer team.

In related research, University of Arizona planetary scientists Yuan Lian and Adam Showman unveiled computer models demonstrating how thunderstorms could power fast-moving jet streams on all the gas giants: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Jet streams - east-west flowing rivers of air - are major drivers of global circulation on Earth.

Images from the Pioneer and Voyager spacecrafts taken in the 1970s and 1980s showed the jet streams in high detail, but left scientists struggling to figure out what causes them to form. Based on their models, Lian and Showman have shown that thunderstorms like those known to exist on Jupiter and Saturn can produce the number and type of jet streams observed on all four gas giants.

Their results, along with the Saturn cyclone images, were presented during the American Astronomical Society's 40th annual Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) meeting currently being held in Ithaca, New York.

Speaking from the DPS meeting, Showman agreed that thunderstorms could power both the giant planets' jet streams and the polar vortices on Saturn.

"That same idea, thunderstorms somehow driving that polar vortex ... has been kicking around for 30 years for explaining jet streams," he said. "For a long time, it's been at the level of a qualitative idea."

Showman said he watched the unveiling of the Cassini images, and "it was breathtaking. They're really amazing."

The southern polar vortex in particular is compelling, he said.

"There are a lot of curly-Q and swirly features in the interior that are really interesting, but I don't think anybody knows what they are. Nobody's tested it yet."

Much more work needs to be done to confirm both sets of results, he said.

Further Cassini observations are planned between now and August 2009 to see how the features evolve as the seasons change on Saturn from summer to fall.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter