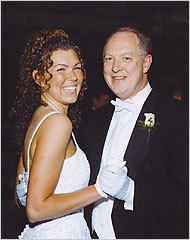

Shannon Neal can instantly tell you the best night of her life: Tuesday, Dec. 23, 2003, the Hinsdale Academy debutante ball. Her father, Steven Neal, a 54-year-old political columnist for

The Chicago Sun-Times, was in his tux, white gloves and tie. "My dad walked me down and took a little bow," she said, and then the two of them goofed it up on the dance floor as they laughed and laughed.

|

| ©Unknown

|

| Shannon Neal says her debutante ball on Dec. 23, 2003, which she attended with her father, Steven, was the best night of her life. A few weeks later, her father, who was 54 at the time, killed himself.

|

A few weeks later, Mr. Neal parked his car in his garage, turned on the motor and waited until carbon monoxide filled the enclosed space and took his breath, and his life, away.

Later, his wife, Susan, would recall that he had just finished a new book, his seventh, and that "it took a lot out of him." His medication was also taking a toll, putting him in the hospital overnight with worries about his heart.

Still, those who knew him were blindsided. "If I had just 30 seconds with him now," Ms. Neal said of her father, "I would want all these answers."

Mr. Neal is part of an unusually large increase in suicides among middle-aged Americans in recent years. Just why thousands of men and women have crossed the line between enduring life's burdens and surrendering to them is a painful question for their loved ones. But for officials, it is a surprising and baffling public health mystery.

A new five-year analysis of the nation's death rates recently released by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the suicide rate among 45-to-54-year-olds increased nearly 20 percent from 1999 to 2004, the latest year studied, far outpacing changes in nearly every other age group. (All figures are adjusted for population.)For women 45 to 54, the rate leapt 31 percent. "That is certainly a break from trends of the past," said Ann Haas, the research director of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.By contrast, the suicide rate for 15-to-19-year-olds increased less than 2 percent during that five-year period - and decreased among people 65 and older.

The question is why. What happened in 1999 that caused the suicide rate to suddenly rise primarily for those in midlife? For health experts, it is like discovering the wreckage of a plane crash without finding the black box that recorded flight data just before the aircraft went down.

Experts say that the poignancy of a young death and higher suicide rates among the very old in the past have drawn the vast majority of news attention and prevention resources. For example, $82 million was devoted to youth suicide prevention programs in 2004, after the 21-year-old son of Senator Gordon H. Smith, Republican of Oregon, killed himself. Suicide in middle age, by comparison, is often seen as coming at the end of a long downhill slide, a problem of alcoholics and addicts, society's losers.

"There's a social-bias issue here," said Dr. Eric C. Caine, co-director at the Center for the Study of Prevention of Suicide at the University of Rochester Medical Center, explaining why suicide in the middle years of life had not been extensively studied before.

There is a "national support system for those under 19, and those 65 and older," Dr. Caine added, but not for people in between, even though "the bulk of the burden from suicide is in the middle years of life."

Of the more than 32,000 people who committed suicide in 2004, 14,607 were 40 to 64 years old (6,906 of those were 45 to 54); 5,198 were over 65; 2,434 were under 21 years old.

Complicating any analysis is the nature of suicide itself. It cannot be diagnosed through a simple X-ray or blood test. Official statistics include the method of suicide - a gun, for instance, or a drug overdose - but they do not say whether the victim was an addict or a first-time drug user. And although an unusual event might cause the suicide rate to spike, like in Thailand after Asia's economic collapse in 1997, suicide much more frequently punctuates a long series of troubles - mental illness, substance abuse, unemployment, failed romances.

Without a "psychological autopsy" into someone's mental health, Dr. Caine said, "we're kind of in the dark."

The lack of concrete research has given rise to all kinds of theories, including a sudden drop in the use of hormone-replacement therapy by menopausal women after health warnings in 2002, higher rates of depression among baby boomers or a simple statistical fluke.

At the moment, the prime suspect is the skyrocketing use - and abuse - of prescription drugs. During the same five-year period included in the study, there was a staggering increase in the total number of drug overdoses, both intentional and accidental, like the one that recently killed the 28-year-old actor Heath Ledger. Illicit drugs also increase risky behaviors, C.D.C. officials point out, noting that users' rates of suicide can be 15 to 25 times as great as the general population.

Jeffrey Smith, a vigorous fisherman and hunter, began ordering prescription drugs like Ambien and Viagra over the Internet when he was in his late 40s and the prospect of growing older began to gnaw at him, said his daughter, Michelle Ray Smith, who appears on the television soap "Guiding Light." Five days before his 50th birthday, he sat in his S.U.V. in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., letting carbon monoxide fill his car.

Linda Cronin was 43 and working in a gym when she gulped down a lethal dose of prescription drugs in her Denver apartment in 2006, after battling eating disorders and depression for years.

Looking at the puzzling 28.8 percent rise in the suicide rate among women ages 50 to 54, Andrew C. Leon, a professor of biostatistics in psychiatry at Cornell, suggested that a drop in the use of hormone replacement therapy after 2002 might be implicated. It may be that without the therapy, more women fell into depression, Dr. Leon said, but he cautioned this was just speculation.

Despite the sharp rise in suicide among middle-aged women, the total number who died is still relatively small: 834 in the 50-to-54-year-old category in 2004. Over all, four of five people who commit suicide are men. (For men 45 to 54, the five-year rate increase was 15.6 percent.)

Veterans are another vulnerable group. Some surveys show they account for one in five suicides, said Dr. Ira Katz, who oversees mental health programs at the Department of Veterans Affairs. That is why the agency joined the national toll-free suicide hot line last August.

In the last five years, Dr. Katz said, the agency has noticed that the highest suicide rates have been among middle-aged men and women. Those most affected are not returning from Iraq or Afghanistan, he said, but those who served in Vietnam or right after, when the draft ended and the all-volunteer force began. "The current generation of older people seems to be at lesser risk for depression throughout their lifetimes" than the middle-aged, he said.

That observation seems to match what Myrna M. Weissman, the chief of the department in Clinical-Genetic Epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute, concluded was a susceptibility to depression among the affluent and healthy baby boom generation two decades ago, in a 1989 study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association. One possible reason she offered was the growing pressures of modern life, like the changing shape of families and more frequent moves away from friends and relatives that have frayed social support networks.

More recently, reports of a study that spanned 80 countries found that around the world, middle-aged people were unhappier than those in any other age group, but that conclusion has been challenged by other research, which found that among Americans, middle age is the happiest time of life.

Indeed, statistics can sometimes be as confusing as they are enlightening. Shifts in how deaths are tallied make it difficult to compare rates before and after 1999, C.D.C. officials said. Epidemiologists also emphasize that at least another five years of data on suicide are needed before any firm conclusions can be reached about a trend.

The confusion over the evidence reflects the confusion and mystery at the heart of suicide itself.

Ms. Cronin explained in a note that she had struggled with an inexplicable gloom that would leave her cowering tearfully in a closet as early as age 9. After attempting suicide before, she had checked into a residential treatment program not long before she died, but after a month, her insurance ran out. Her parents had offered to continue the payments, but her sister, Kelly Gifford, said Ms. Cronin did not want to burden them.

Ms. Gifford added, "I think she just got sick of trying to get better."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter