A study published in the journal Nature suggests that the key to understanding the evolution of bird flight is the angle at which a bird flaps its wings.

The US team found that birds move their wings at the same narrow angle, whether they run, fly or glide.

|

| ©Unknown |

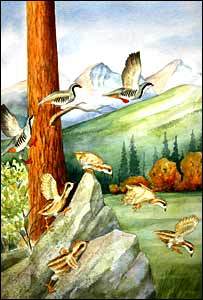

| Birds flap their wings to help propel them up steep inclines |

They conclude that early birds may have begun to fly by simply learning to flutter their wings at the right angle.

The research was carried out by scientists at the Flight Laboratory at the University of Montana.

Professor Ken Dial, lead author of the paper, said: "There has been a fair amount of interest in the origin of birds and bird flight for at least a century-and-a-half, but I think sadly it has been approached from an awkward beginning."

Scientists investigating this area tend to fall into two camps, he said. Those who believe that birds learned to fly from the "top down" - by falling out of trees and gliding, and those who think that birds took to the air from the "ground up" - by running and flapping their wings, possibly to escape predators.

|

| ©Unknown |

| Wings may have evolved to help birds move over obstacles |

However, both of these scenarios suggest that birds would first need to establish a wide range of wing movement in order to become airborne.

Eureka moment

In 2003, Professor Dial and his colleagues published a paper that revealed birds utilise their wings when running up steep inclines.

He explained: "This was an important find - birds exhibit a behaviour we really didn't appreciate before.

"Birds don't just use their wings when they fly or just their legs to run on the flat; in fact, they recruit both wings and legs for them to scale steep inclines, whether it be a boulder, a tree or a cliff."

His new research, he said, uncovered the second half of the story.

Using high-speed video, Professor Dial studied the wing movements of small quail-like birds, called chukars, as the birds ran up steep inclines, glided back down, and flew.

|

| ©Unknown |

| Chicks and adults were filmed as they ran up and flew down ramps |

He told the BBC: "To my amazement, the data kept coming in showing they were not changing [their wing angle] at all."

"This is one of those moments when you slap you forehead and say: 'We've been thinking that the wing-stroke is highly specific for different movements but it turns out that Mother Nature just needs a single wing stroke to accommodate all these behaviours."

The team found the same narrow angle range when they then studied a wide range of different bird species.

The team also looked at the wing movements of fledgling birds as they learned to fly.

Although hatchlings have small stunted wings and are unable to take to the air, the team found that when they ran up steep inclines, they flapped their wings at the same angle as older birds to help speed them up the ramp.

They held them at the same angle in order to glide back down from the incline.

The researchers believe that the baby birds' early wings are similar to the partially formed proto-wings found on some dinosaurs.

Professor Dial said that dinosaurs may have evolved wings to help propel them over rocks and other obstacles that littered their terrain.

As their wings grew larger and strong enough to support their body weight, flapping them at the right angle would have enabled them to take to the air, the team concluded.

Professor Dial said: "That simple wing stroke seems to be elementary to bird evolution and bird ecology to get through the fledgling stage."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter