The risk of a volcanic eruption on Iceland's Reykjanes Peninsula is once again growing as magma continues to pool in the area 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) north of the fishing town of Grindavík, according to the Icelandic Met Office (IMO).

An estimated 318 million cubic feet (9 million cubic meters) of magma now sits beneath Svartsengi, which is home to the Blue Lagoon resort and Svartsengi geothermal power plant. That's equivalent to the volume of around 3,600 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Five days ago, on Feb. 1, the volume of magma was reported to be 230 million cubic feet (6.5 million cubic m), with the IMO already warning officials that the volcano was primed to erupt again. "The estimated amount of magma under Svartsengi has now reached the lower limit of the amount believed to have accumulated there before the last eruption," IMO representatives wrote in a translated statement on Monday (Feb. 5).

Between 318 million and 460 million cubic feet (9 million and 13 million cubic m) of magma are thought to have accumulated in the same chamber before an eruption on Jan. 14 that sent lava coursing toward Grindavík.

The land began rising again following the eruption and continues to inflate as molten rock gathers under the surface, although the rate has slowed in the last few days, according to the IMO statement. This pattern is the same as land movements recorded in the weeks and days preceding the eruption on Jan. 14 and a previous eruption in December 2023.

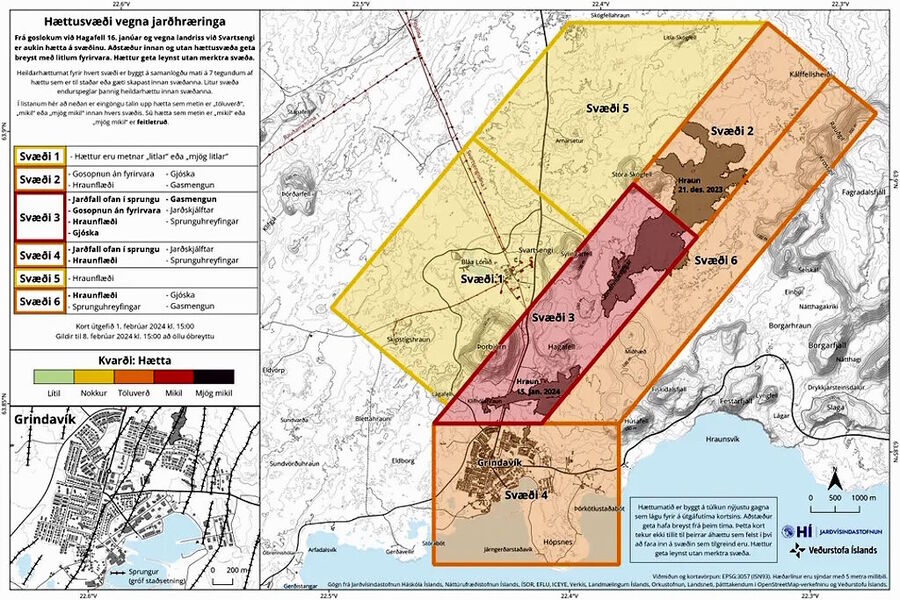

Predicting when and where an eruption will take place is not possible. A hazard map released by the IMO shows the areas believed to be at greatest risk, with a corridor stretching from Grindavík in the south to Stóra-skógafell to the northeast. Svartsengi, where the magma is pooling, is considered at a very low risk of a volcanic eruption.

"We saw a substantial increase in the pressure in the boreholes before the dyke intrusion on Nov. 10," Lilja Magnúsdóttir, the director of resource management at HS Orka geothermal power plant in Svartsengi, told Live Science in an email. A similar increase in pressure was also recorded ahead of the eruption on Dec. 18, alerting staff to the possibility that another dike intrusion could culminate in an eruption.

"Around 40 [to] 50 minutes later, it erupted," Magnúsdóttir said. "So we made an automatic program to detect this signal. If an alert is triggered, the program sends a warning email to our shift at HS Orka and to the Icelandic Meteorological Office."

The program issued a warning in the early hours of Jan. 14, foreshadowing an eruption four hours and 20 minutes later, Magnúsdóttir said. "We were also able to predict that it would erupt further south than in the previous eruption," thanks to a stark change in pressure on the southern boundary of the geothermal reservoir, she added.

Sascha Pare is a U.K.-based trainee staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master's degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe.

There's a deeper 'popular' zone at @30km that suggests other solvents get a look in too but below 30 there may be more variable TPs.