A paper published in the Planetary Science Journal reports a surprising new twist in the mystery of the Geminids, a strong annual meteor shower that has puzzled astronomers for more than a century.

"Our work has upended years of belief about 3200 Phaethon, the source of the Geminids," says co-author Karl Battams of the Naval Research Lab. "It's not what we thought it was."

The Geminids peak every year in mid-December, scattering hundreds of bright meteors across northern winter skies. Numerically it is the best meteor shower of the year.

As meteor showers go, Geminids are newcomers. They first appeared in the mid-1800s when an unknown stream of debris crossed Earth's orbit. Surprised, 19th century astronomers scoured the sky for the parent comet, but they found nothing. The search would continue for another 100 years.

Enter NASA. In 1983, the space agency's Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) found an object now called "3200 Phaethon." It was definitely the source of the Geminids. The orbit of 3200 Phaethon was such a close match to that of the Geminid debris stream, no other conclusion was possible. Yet here was a puzzler: 3200 Phaethon appeared to be a rocky asteroid.

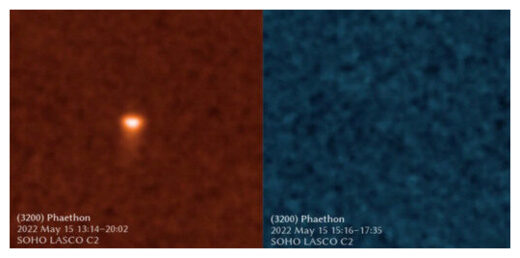

Asteroids are not supposed to make meteor showers. Unlike comets, they don't have tails and they don't spew meteoroids. Yet 3200 Phaethon was different. In 2009 and 2012, NASA's STEREO spacecraft caught 3200 Phaethon sprouting a tail when it passed close to the sun. Apparently, intense solar radiation was blistering meteoroids off 3200 Phaethon's rocky surface. Astronomers dubbed it a "rock comet," and the mystery was solved.

Or was it?

Astronomer Qicheng Zhang, lead author of the new paper, was never convinced. For one thing, the Geminid debris stream is massive (1013 kg), while the tail of 3200 Phaethon is puny, providing less than 1% of the mass required to explain the Geminids.

"The tail we see today could never supply enough dust to supply the Geminid meteor shower," says Zhang.

And therein lies the twist. Meteor showers are made of meteoroids, not gas. Suddenly, the Geminids are a mystery again.

"We're back to square one," says Zhang. "Where do the Geminids come from?"

3200 Phaethon is still the main suspect. At least one study suggests that Geminid meteoroids are 1,000 to 10,000 years old. Perhaps something hit the asteroid millennia ago. Phaethon's rapid rotation makes it susceptible to sudden episodes of mass loss, so even a relatively small impact could create the necessary meteoroids.

The best way to test this idea is to look at the surface of Phaethon with a space probe. Japan plans to do just that. JAXA is building a spacecraft called DESTINY+ to fly by 3200 Phaethon for a closer look. Launch is scheduled for 2025.

Until then, the Geminids remain a beautiful mystery. Look for them streaking across the night sky this week!

Reader Comments

I am distracted being sleep deprived, stoned, drunk, still a little tweaked on coffee and ephedrine from earlier.. don't mind me. This is my brain scrambled eggs.