One of the most enduring mysteries within archaeology revolves around the identity of Punt, an otherworldly "land of plenty" revered by the ancient Egyptians. Punt had it all — fragrant myrrh and frankincense, precious electrum (a mixed alloy of gold and silver) and malachite, and coveted leopard skins, among other exotic luxury goods.

Despite being a trading partner for over a millennium, the ancient Egyptians never disclosed Punt's exact whereabouts except for vague descriptions of voyages along what's now the Red Sea. That could mean anywhere from southern Sudan to Somalia and even Yemen.

Now, according to a recent paper published in the journal eLife, Punt may have been the same as another legendary port city in modern-day Eritrea, known as Adulis by the Romans. The conclusion comes from a genetic analysis of a baboon that was mummified during ancient Egypt's Late Period (around 800 and 500 BCE). The genetics indicate the animal originated close to where Adulis would be known to come into existence centuries later.

Many mentions, few details

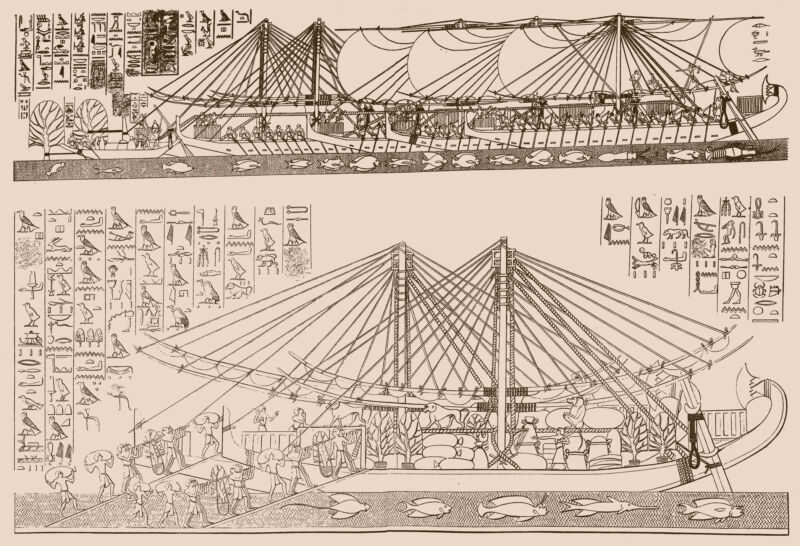

The most detailed depictions of Punt come from a mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari dedicated to Queen Hatshepsut, the first female ruler to declare themselves pharaoh. Commissioned sometime in 1493 BCE, Hatshepsut's expedition to Punt was considered politically and religiously significant, as the ancient Egyptians apparently had lost their connection to the "God's Land" over the centuries. Stone reliefs illustrate the expedition with scenes of Hatshepsut's flotilla of ships arriving at a mysterious land, a village of beehive-shaped houses on stilts, all sorts of exotic flora and fauna (including myrrh trees and baboons), and the successful voyage back.

After Hatshepsut, the last known expedition to Punt occurred during the 12th century BCE under Ramses II, commonly known as Ramses the Great. A surviving papyrus describes the sailing of ships bearing cargo potentially down the Red Sea to Punt. But, like all other historical references, it makes no exact mention of how long these voyages took or where the ancient Egyptians went.

Despite the lack of precise directions, archaeologists have long entertained theories on Punt's locale, said Josef Wegner, a professor of Egyptology and Egyptian archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the new eLife paper.

"Probably by the early 1900s and much of the 20th century, a lot of people would say that Punt was in the Horn of Africa. Somalia was frequently identified as Punt to the point where, sometime in the country's history, the northernmost province of Somalia was actually named Puntland," said Wegner. "There was also a debate whether it was both sides of the Red Sea. I think the prevalent opinion in Egyptology has been on the African side of the Red Sea from roughly the coastal areas of Sudan and modern Port Sudan all the way down to Eritrea and the northernmost point of Ethiopia."

DNA evidence

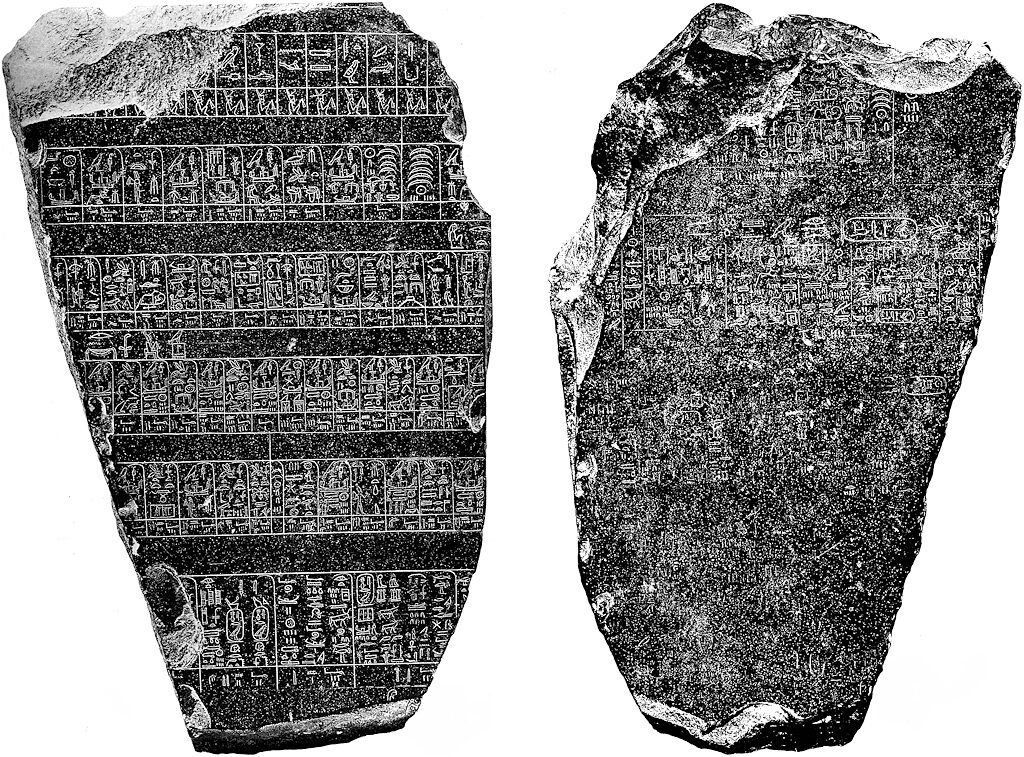

In 2020, a team of researchers led by Nathaniel Dominy, an anthropologist at Dartmouth College, examined radioactive isotopes of strontium and oxygen in the mummified remains of baboons dating back to the New Kingdom (1550 to 1069 BCE) and the Ptolemaic period (305 to 330 BCE). Mapping the isotopic signatures to their approximate geographies, Dominy and his colleagues discovered some of the animals weren't native to Egypt, likely hailing from somewhere in the area of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Somalia.

"The strontium values, for example, like in your molar teeth, reflect where you were when you were five, six, or seven years old. You move around as an adult and you live in different places but you retain that sort of fingerprint of your early childhood in a particular region," said Dominy. "This was a cool project because we were able to show that some of those baboons spent their entire lives in Egypt, but others we could tell came from some distant place."

This female monkey, dating back to 800 and 500 BCE, was among 14 specimens examined, which were originally sourced from the Musée des Confluences in France. Recovering DNA, let alone mitochondrial DNA, from bones that old isn't easy: Genetic material decays over time, and cross-contamination from surrounding environmental microbes can happen. This female was the only sample where the DNA was intact enough to be analyzed.

It helps a couple of things make a baboon ancestry test pretty straightforward. Mainly, there has been a concerted effort to analyze ancient DNA and compare the results to current populations, essentially creating a baboon family tree, said Kopp. That is made all the easier because there isn't significant genetic variation within the mitochondria's unique genome across a baboon generation.

"There are parts of the mitochondrial genome that mutate at different rates, but we also have sub-parts where we have a lot of mutations, but it's still in timeframes," said Kopp. "Evolutionarily speaking, a thousand years isn't that long, actually. And when you break it down to a baboon generation, which we estimate is at least 12 years, it's actually not that much time to accumulate so many differences that you couldn't connect the genomes."

According to her mitochondria DNA, this baboon was related to a modern-day species known as Papio hamadryas, found in the plains and open-rock areas of the Red Sea Coast. Additionally, she had a line on her tooth, called an enamel hypoplasia, that develops in response to stress. Dominy said this could have resulted from being captured at a young age, possibly around 2 years old, and enduring a grueling sea voyage thousands of miles north to Egypt. There, she lived out the rest of her days as a venerated embodiment of Thoth, the god of wisdom, before dying around 6 or 7 years old.

Genes, history, and Punt

But the question remains: Where was Punt? Dominy and Kopp are forced to speculate a bit. They note that the specimen's origin was close to where the port city of Adulis eventually came into being, which was part of the Aksumite Empire (it's in modern-day Eritrea). They suggest the same port may have been Punt in the past.

"The beauty of this project is that the mummies we studied are older than the first account of Adulis. So what we think we can say is that Adulis must have existed a couple hundred years before the first existence that we have of its historical record," said Dominy. "That fills in the gap because Punt is no longer used by the Egyptians, and Adulis comes into play. These baboons kind of connect Punt and Adulis in time to connect those dots."

Adulis was first mentioned during the early Ptolemaic period in the third century BCE. Wegner of UPenn said the Ptolemies were famously known for exporting war elephants from Adulis for their many military campaigns in modern-day Syria. At that time, Adulis would have been a highly urbanized state with monumental architecture and a well-developed harbor. Nothing in ancient Egyptian accounts and depictions of Punt comes close to that.

"I think saying Adulis equals Punt is going too far from an archaeological standpoint," said Wegner. "I think it would lend credence to the idea that where Adulis developed in later times equates to the region the Egyptians talk about as the land of Punt. It could well be that there was something there going back that far, a coastal settlement or perhaps a substantial town. That's a possibility for archaeologists to investigate further."

Dominy and Kopp acknowledge it's a bold statement equating Punt with Adulis. But they hope their boldness guides current and future archaeological research at Adulis and anywhere else within the region, encouraging insights into how commerce catalyzed ancient Egyptian maritime technology or how human trade influenced wildlife diversity.

Maybe the most important question is yet to be answered: Why did the ancient Egyptians revere baboons? They weren't native to Egypt, and in the environments the animals shared with humans, they were considered more of a nuisance than the avatar of a sacred deity.

"The leading idea is the Egyptians would have seen them in their natural environment, orienting and vocalizing towards the rising sun in the morning," said Dominy. "This natural behavior would have resonated with the Egyptians religiously, and so for that reason, this animal becomes privileged over other animals."

Perhaps finding Punt will answer this question and many more that render aspects of ancient Egypt a beguiling enigma.

Miriam Fauzia is a freelance science reporter currently based in northern Virginia. She holds a master's degree in immunology from the University of Oxford and another in journalism from Boston University. Her work has appeared in Popular Mechanics, The New York Times, Inverse, The Daily Beast, and VICE, among other publications.

Reader Comments