Icy bodies at Solar System's edge found during target hunt for NASA spacecraft.

© Getty ImagesAn artist's interpretation of what the sun might look like from the Kuiper Belt.

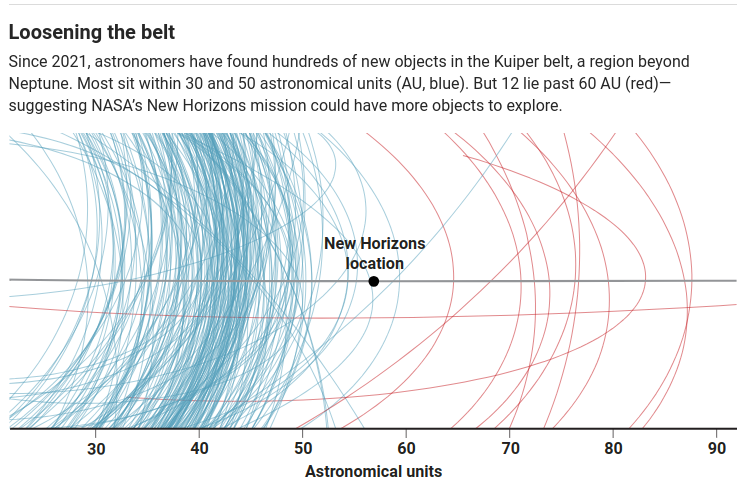

There just doesn't seem to be enough of the Solar System. Beyond Neptune's orbit lie thousands of small icy objects in the Kuiper belt, with Pluto its most famous resident. But after 50 astronomical units (AU) — 50 times the distance between Earth and the Sun — the belt ends suddenly and the number of objects drops to zero. Meanwhile, in other solar systems, similar belts stretch outward across hundreds of AU. It's disquieting, says Wesley Fraser, an astronomer at the National Research Council Canada. "One odd thing about the known Solar System is just how bloody small we are."

A new discovery is challenging that picture. While using ground-based telescopes to hunt for fresh targets for NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, now past Pluto on a course out of the Solar System, Fraser and his colleagues have made a tantalizing, though preliminary, discovery:

about a dozen objects that lie beyond 60 AU — nearly as far from Pluto as Pluto is from the Sun. The finding, if real, could suggest that the Kuiper belt either extends much farther than once thought or — given the seeming 10-AU gap between these bodies and the known Kuiper belt — that a "second" belt exists.

The discovery, being prepared for publication and not yet peer reviewed, is supported by measurements from New Horizons itself, which at 57 AU continues to streak beyond the edge of the known Kuiper belt. Many of its instruments are in hibernation, but a dust counter

has run continuously during the mission. Dust is a telltale sign of colliding planetary bodies, and so the New Horizons team expected the amount of dust to fall off steeply after the probe left the Kuiper belt, where it had

rendezvoused with an object called Arrokoth. Instead, "The number of impacts is not declining," says Alan Stern, the mission's principal investigator and a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute.

"And the simplest explanation for that is that there is more stuff out there that we haven't detected."

Astronomers outside the team are intrigued but want to see more evidence. "If there really is a new belt, that's a superexciting thing," says Pedro Bernardinelli of the University of Washington. However, the findings are hard to reconcile with unpublished results

from a recent survey of the outer Solar System using the 4-meter Víctor M. Blanco Telescope in Chile. It surveyed a different slice of sky and turned up only one object beyond 50 AU. Other surveys have also come up dry. "Why are we not seeing these things?" Bernardinelli asks. "Did everyone get unlucky? It's possible, but it's hard."

Stern would welcome more icy bodies to study. After threats to shift New Horizons from planetary science to heliophysics — the study of the Sun and its plasma-filled envelope —

NASA relented last week, extending the mission's current focus until the decade's end. That means the probe could still visit another object like Arrokoth, if one exists, Stern says. "We have the opportunity to do science that we know we can do — and can't be done other ways — for a very long time."

For years astronomers have scouted targets for the mission using a wide-field camera on Japan's 8.2-meter Subaru Telescope, on Hawaii's Mauna Kea. The giant telescope is needed, Fraser says, because Kuiper belt objects, so faint and slow moving, "are a pain in the butt to find." Targets for New Horizons are even harder to see because the spacecraft, as seen from Earth, appears to be flying straight toward the bright center of the Milky Way, dazzling instruments.

To boost the signal, the team electronically combines hundreds of images from a night of observation, hoping a bright blob will appear along a likely trajectory. Initially, the team examined the images manually, sifting through 15,000 candidates a night. "You go blind pretty quickly," Fraser says. Now, artificial intelligence makes the screening much less painful. "We went from a week of agony for an army of people to 6 hours of vetting."

© (GRAPHIC) D. AN-PHAM/SCIENCE; (DATA) SIMON PORTER/SWRI/JHU APL

The result was the 12 far-out objects. They add to a clue: three blips spotted by

star-tracking sensors on the Hubble Space Telescope in its first 20 years, says Hilke Schlichting, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Los Angeles. The sensors, which stare unendingly at single stars to help with pointing the telescope, briefly dimmed for a fraction of a second, suggesting the stars were eclipsed by unknown Kuiper belt objects crossing in front of them. "Is there a larger population beyond 60 AU? There could be," Schlichting says. "Maybe that's what we're seeing. I'm not sure."

The team has done its best to confirm the objects' orbits, by capturing them at three or four spots along their apparent courses. They think one reason the Blanco telescope hasn't turned up similar results might be because the objects are clustered near New Horizons's path, perhaps by Neptune's gravity, Fraser adds.

Just as intriguing as the new objects is the apparent gap between 50 and 60 AU, says Mihály Horányi, a space physicist at the University of Colorado Boulder who oversees New Horizons's dust counter. "One way or another, something is responsible for maintaining that gap." In other solar systems, planets orbiting within a dusty disk carve gaps by hoovering up material. But no large planet has been seen in the gap. The gap could also be a relic from the Solar System's infancy, caused by waves of pressure in the disk.

The team returned to Subaru for several days last month, using a new optical filter that Fraser says will let them see fainter and smaller objects. They are now analyzing the data. If the second Kuiper belt is real, more than a dozen new distant bodies should emerge, he says. "And if that expectation isn't met, then we have completely missed something."

Where's the beef?