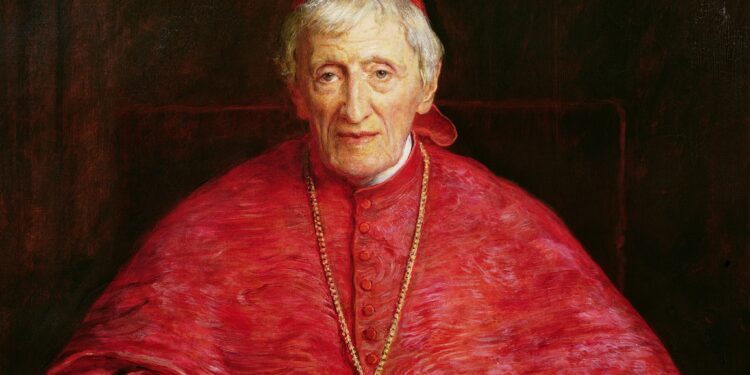

Even though schools are ancient, and universities are medieval, we only began worrying about the university in the 19th Century. This is when the church began to wane and the state began to wax in the eye of the university. The most famous writer in England about the university was Cardinal Newman. He gave a series of lectures in the 19th Century published under the title of The Idea of a University. Newman was a worrier. He worried about the state. Then he worried about the church. Finally he worried about the university.

Newman's argument, in short, was that the university had become a superimposition of several ideas: one was religious, one was what he called liberal and one was utilitarian. A few years ago I wrote an academic article explaining that the university is a composite entity: a superimposition of an 'eternal' institution, an 'immortal' institution and an 'immediate' institution. Fancy words: but I wanted to make Newman's conceptions clearer than I think they have been to even those people influenced by his 'idea' - all those Leavises and Scrutons. The university is built on three contradictory ideas:

- Eternal. The university has always been, in part, a community which enables the learned to offer thanks to God or the gods for the blessings of life through learning: and to pursue truth without care for fame or even contributing to the sum of human knowledge. Here the academic is closest to an ancient philosopher or a monk.

- Immortal. The university has always been concerned with learning for its own sake: and this is where we contribute to our civilisation and to the state of truth as we see it in our own time. Here the academic is the scientist or historian or modern philosopher: writing books and articles.

- Immediate. The university, in addition, has always been concerned with serving society in some fairly comprehensible respect: either by generating lawyers, medics and, in the last century or so, engineers, or by generating bits of academic learning which are incidentally useful: whether for building bombs, cyclotrons and microchips, or for consoling the afflicted.

So here is a list.

- The university has been SECULARISED. Formerly at the service of the church, or a religious state (which was, anyhow, extremely small in scale), it is now at the service of a God-is-dead state. This is Hobbes's 'mortal god' of the Leviathan: the powerful technologised military-industrial corporate-capitalist-bureaucratic state. No longer unified by religion, or dignified by aristocracy, it is only civilised by its own traditions, in so far as they survive the unification which comes from the imperatives of the state. Hence 'impact', 'relevance', 'models', 'settled science' and other sad words.

- The university has been made UTILITARIAN. A 'utility' is simply something useful. And a useful thing is a thing which enables us to get another thing. The language of utilitarianism is the language of instrumentality: of using things — for instance, mathematics, logic, ethics, physics - to get other things - such as status, funding, computer models, a Nobel Prize, influence and power. The old idea of knowledge-for-its-own-sake has been, if not entirely replaced, then supplemented by and to some extent subordinated to the new idea of knowledge-for-use. By this standard, the whole purpose of the university is to better something: at the minimum, to better the lives of the people who study there, at the maximum, to better the entire life of the society. No longer is the university an end in itself: it has to justify its existence by its results, outputs, impacts — by its making us feel safer or better.

- The university has been CENTRALISED. A century ago, or earlier, the academics could study whatever they wanted, for its own sake, or for God's sake. But now academics have to satisfy universal protocols and conventions. Everyone writes and teaches within a sharp haze of criteria, classifications and requirements couched in what has become our standard composite language of market, monopoly and bureaucracy (that is, in terms of what sells, in terms of what we are forced to buy, and in terms of what rules we buy and sell by). The grand incentives in the modern university are wholly centrally controlled. There are enormous funding agencies, some public, some private, which offer vast sums for research if it can successfully appear to tick the appropriate commercial-corporate-bureaucratic boxes. If one can ape the received pronunciation of one's established academic overlords then one can prosper. But one has to bow and scrape, and work for a machine.

- The university has EXPANDED. Our societies are extremely wealthy: wealthier than ever. But our universities are colossal in scale and extent. We educate a greater proportion of the population in universities than ever before. There are more students, more universities and more academics than ever before. The result is mediocrity. If there are too many towers, they cannot all be made of ivory. 'Educate, Educate, Educate' said Tony Blair in the 1990s. "More will mean Worse," said Kingsley Amis in the 1960s. Across the world now, societies are divided more or less neatly between a higher educated class that has been educated out of its common sense and a class that lacking such an education is entirely dependent on common sense. Higher education on such a scale has created an establishment which exhibits a remarkable new phenomenon, the arrogance of informed mediocrity, the creation of a mediocre elite. Entitled without being enlightened.

- The university has been broken into SPECIALISATIONS. Faculties, departments, fields, subfields. Everyone contributes to one of a thousand separate literatures. To some extent, specialisation is a countervailing force to centralisation, but only to some extent. Unfortunately, specialisation has in the long run tended to reinforce rather than subvert the uniformity of modern public culture: since it has undermined the claim of the university to say anything of general significance to society. Instead there are many special subjects and special theories, all clamouring for attention: some of which have success in claiming attention - if they can relate themselves to a crisis - while most of the others have to find some way of signalling their conformity to the uniformity imposed by all the features of the modern university described above. The university no longer believes in 'universality'. It is wholly opposed to anything like a broad sensibility, a sense of proportion, learning, general knowledge or wisdom.

- The university has been rendered IRRELEVANT. As the universities have been assimilated to the state, and asked to be more relevant, they have become less relevant. Specialisation is the likely cause. No one reads enough to be able to frame a general argument. Older figures such as Ernest Gellner and Alasdair MacIntyre, who came through in the 1950s, were still able to write about more or less everything. But the figures who came through in the 1960s were victims of rising specialisation. Academic literature is now Byzantine, vacuous, woodenly professional, technical to a fault, and committed to proclaiming a relevance it cannot possess. Paradoxically, the only two ways for a modern academic to become well known, and still remain intellectual, are 1. to become a simplifying and agreeably soporific figurehead of the new establishment like Brian Cox, David Olusuga or Devi Sridhar: or 2. to be 'cancelled' like Bret Weinstein and Kathleen Stock (or, if not exactly cancelled, then certainly to be considered suspect for going off piste, like Nigel Biggar and Jordan Peterson). Most other figures who remain within the pale of respectability are without characteristics. The university is becoming a vast certification system for those who want to rise within a centralised system. Its literatures have been subinfeudated to a fault. The fields are small. No one claims to know anything about another field. Criticism of any other field is forbidden. Everything has to be tolerated and cannot be criticised. One's academic allies are the guardians of truth. But academic truth has become so miniaturised that a common culture can only be achieved amongst academics if they all subscribe to the same moral and political ideology.

- The university has been subjected to strange new IDEOLOGIES. The university has adopted administrative habits of mind which are alien to scholarship. It has become dominated by liberal platitudes, by 'diversity, equity, inclusion' rigmaroles, by 'decolonisation' protocols, by 'pandemic' tittle-tattle, by 'climate' flim-flam and now by the 'AI' voodoo. All this is because centralisation requires a focus: and the focus is more stimulating to the grey bureaucratic paymasters if it is something to do with care and crisis on a great scale. The more immediate the crisis the better, for the modern immediate university. So academics, if they want to be successful, sculpt their subjects to make them 'relevant' to fashionable concerns. Fatuity is no objection. (In this regard, let me say that after Toby Young drew our attention to his father and Edward Shils's piece on 'The Meaning of the Coronation' from the Sociological Review of 1953, I checked to see what the Sociological Review was up to 70 years later. The first piece I saw had, as its first sentence, "Toilets are political spaces.") It is hard to get serious thought off the ground. Not only does all work have to be written in the same rigor-mortising English-as-a-second-language style, it also has to be adorned with the same politically correct marginal decorations. In the sciences, it has to proclaim support for the pharmaceutical or climate conspiracies. Religious opinions, unless of a 'minority' religion, are out. All academics are on the left: either in a first, neutral, sense in which they more or less adopt the politics of the interventionist state (the state which supports the modern university), or in a second, more political, sense in which they are actively leftist in their politics: making a moral virtue out of the relevance of their study to the deliverance of contemporary humanity, or nature or, indeed, the planet.

- The university has been GLOBALISED. This is not a British problem, or a problem about universities operating in the English language. It is ubiquitous. Universities are still places where good scholarly work can be done, usually interstitially. But much work is dross, morally inflected or politically infected, built on the shallow sands of crisis, or specialised to a fault, or second-rate by design. It all contributes to the collapse of any general intellectual culture within any particular state. The centralisation I mentioned above is doubtless encouraged by the state, but it gestures beyond the state. The problem is on a world scale. Universities, tolerated within every state, are discovering unity in a set of ideological precepts which commit them to the dissolution of the civilisations of their own states, for the sake of a generalised capitalist-corporatist system which is a grand public-private conspiracy of elite nowhereness against somewhereness. This system is feeding centre-left authoritarianism. The centralisation of funding has created a system of capture and criterion control which perpetuates not only a strange abstract and universalising rhetoric but also distorts the minds of the rising scholars who are doing what scholars have always done and copy their immediate predecessors, assuming that they are masters.

The university has been SECULARISED, INSTRUMENTALISED, CENTRALISED, EXPANDED, its subjects broken into many SPECIALISATIONS, consequently rendered ironically IRRELEVANT, so that its culture can be unified only by IDEOLOGY, and now all this is happening on a GLOBAL scale.

It is very hard to imagine how we can reverse engineer the modern state-ideologised corporate-administrative hyper-specialised unconsciously-leftist university with its mass of state and global functionaries. It would be pleasant to witness the breaking of peer review and the established incentive structures. It would be good if publication was somehow separated from certification. Everyone ought to write less and read more. Honest nepotism would be far preferable to the imposition of gatekeeping protocols. Schools should feed off their own roots. Too many appointments are international. The entire culture has too much transparency flowing through it, courtesy of the world wide web. The inability of the university to say anything critical about COVID-19 was a stunning exhibition of how broken it is.

As long as the university remains as it is, there is nothing to be done but continue to work in our corners. The university is a modern Babel, in which everyone talks about impact, and in which no one has impact, because the system has suffered from unregulated growth and has been retro-regulated by those who do not understand it or operate under the wrong imperatives, and now shape it with their shekels.

I doubt that even most academics would agree with all of this. There are too many internal barriers to seeing the problem clearly. Some good work is still being done. The young are exposed to bits of proper learning alongside the insinuations and incentives of a utilitarian and moralitarian culture. But the system only tolerates independence of mind within certain strict limits. Academics are at the moment not much more than the worker ants and bottom feeders of the global elite.

In the 19th and 20th Centuries the state and society corrupted the university. Now, the university is taking its revenge and corrupting state and society.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

But alas no

For the independent intellectual is to be banished, yes, replaced by ideology of a mind numbing kind that fits with narratives that suppress and are full of falsehood and misinformation.